Immune study brings safe, accessible wound treatment in reach

A blood cell key to repairing the body can be exploited, research shows, to quickly seal wounds, heal from a heart attack and more.

A new treatment built from immune cells in the blood could be key to a quick, adaptable and low-risk way to heal wounds sooner.

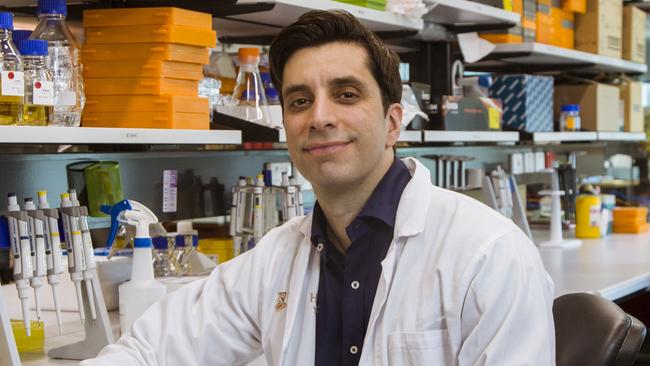

Research from Monash University’s Australian Regenerative Medical Research Institute has been billed as a potential off-the-shelf immune booster after scientists isolated a blood cell that could drive the body to heal quicker when injected into an injury.

Regulatory T cells activate genes in the body responsible for tissue healing and immune response. The study’s lead researcher, Mikael Martino, compared them to a triage doctor, directing resources effectively to close a wound.

“These regulatory T cells have been shown to accumulate within injured tissues, facilitating repair or regeneration in multiple tissues and organs,” Professor Martino said. “(The) cells can be cultured and kept on the shelf prior to administration, which means they could be banked or even become off-the-shelf products which can be injected.

“(Injecting) regulatory T cell numbers locally as early as possible after tissue damage would likely provide maximum benefit.”

Working across bone, skin and muscles, the treatment excited experts because it seemingly had no risk of being rejected by the body. Cells could come from genetically dissimilar donors, or be synthesised, and still work in any patient.

The “universal therapy” was outlined in Nature Communications. It was also found to potentially treat some genetic conditions.

“In animal models, these cells have been shown to improve cardiac repair post-heart attack and bone remodelling in … brittle bone disease.”

By flooding out immune cells that prevent healing, the therapy leaves parts of the body more resilient in future, which helps offset conditions like brittle bone disease where the body struggles to build up and restore collagen.

Many vulnerable populations are burdened with slow healing wounds on top of existing health defects. Not only can these impact quality of life, they leave people at risk of infection or sepsis.

Diabetics and the immunocompromised have to be especially vigilant, and could be aided by advances in wound healing. Sepsis makes up 15 per cent of all ICU admissions.

Despite wide-ranging applications, using immune cells to boost regeneration has been relatively unexplored in the past. A prior study by Monash and Professor Martino used neurons to similarly heal wounds sooner.

It found the manipulation of a specific sensory nerve in the neuro-immuno-regenerative axis could quicken healing up to 2.5 times the natural rate.

“I’m interested in understanding how the immune system functions with tissue repair and regeneration,” Professor Martino said.

“If a wound is there for a very long time and never really heals, you will increase the chance of getting sepsis. So one of the critical things is to make sure to heal these wounds as soon as possible.

“If you’re a patient of a certain age, to change (a) bandage and physically clean the wounds every day is very costly. It’s very time consuming as well, and for the patient, it can be quite painful.

“In very extreme cases, the only solution is amputation to avoid the wounds stretching further and to avoid infection.”