If the US health system sneezes, does Australia catch pneumonia?

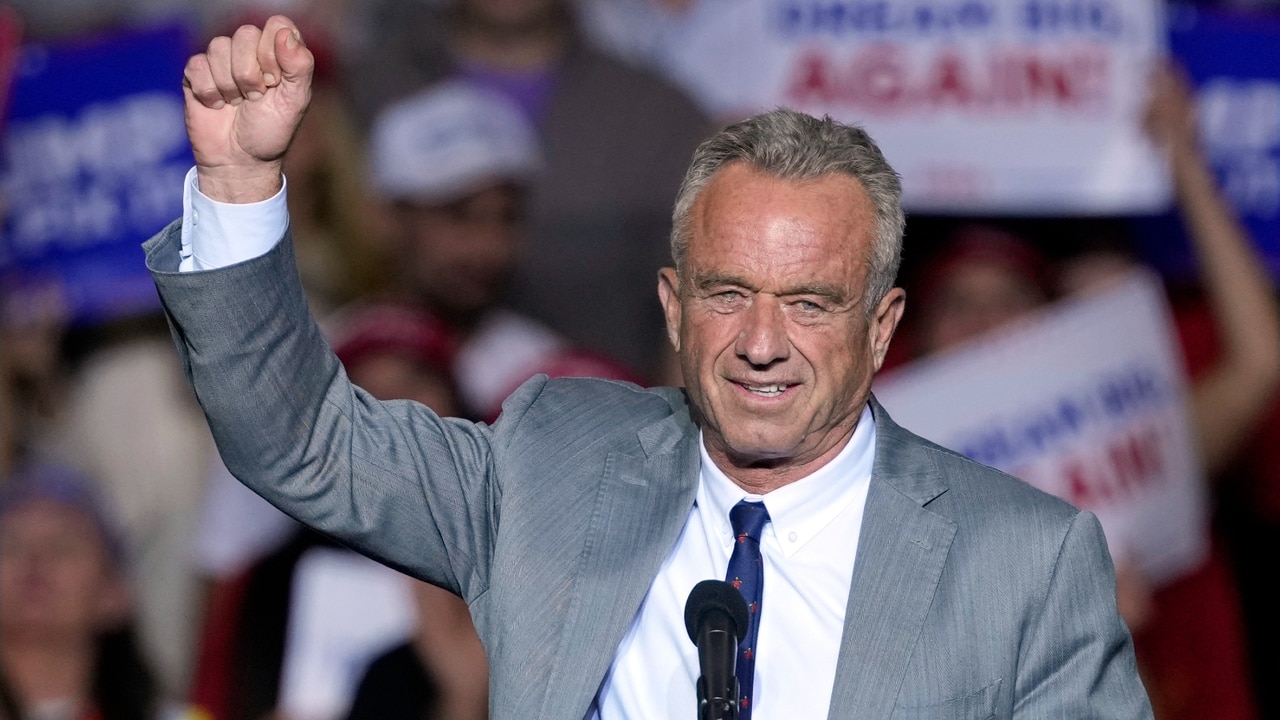

Donald Trump’s nomination of Robert F Kennedy Jr and Dr Mehmet Oz for key health positions have provoked uproar. But what might their policy approach mean for Australia?

When Donald Trump named Robert F Kennedy Jr as his pick for health secretary – the equivalent of Australia’s federal health minister – it caused near-apoplexy among many of America’s most senior health leaders. The American Public Health Association didn’t pull its punches. “To effectively lead our nation’s top health agency, a candidate should have the proper training, management skills, temperament and the trust of the public,” said the organisation’s executive director, Dr Georges Benjamin.

“Unfortunately, Mr Kennedy fails on all fronts.”

“I can’t think of a darker day for public health and science itself than the election of Donald Trump and the nomination of Robert F. Kennedy Jr as secretary of health,” Lawrence Gostin, director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, told Time Magazine.

“To say that RFK Jr is unqualified is a considerable understatement … he spent his entire career fomenting distrust in public health and undermining science at every step of the way.”

But the outraged howls of scientists and health officials will count for little because the public seems to love RFK Jr and Mr Trump’s other pick as health system leader, Dr Mehmet Oz. “Kennedy and Oz developed such a large audience because they speak constantly to issues such as obesity, anxiety, autism, chemical dependence and chronic pain that truly do trouble Americans,” Dr Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, a prominent US political commentator, wrote in an opinion piece carried by MSNBC last week.

“The two … give voice to their audiences’ frustrations with the insufficiency of our health care system to solve or address their most pressing problems. These messages especially resonated with Americans during the pandemic. Kennedy and Oz took aim at how the government handled it – and rose to new heights of popularity.”

The health systems in the US and Australia are very different and we must be cautious in drawing too many direct comparisons. Unlike Australia, the US has no universal health system and tens of millions of Americans have little access to quality care. The appointment of health secretary is made by the president, with no requirement that the appointee is an elected representative, unlike Australia. Yet there are disturbing parallels too. Suspicion, distrust, and spread of misinformation and disinformation across social media are rife in both countries. Should we be worried that, if the American health system sneezes, Australia will catch pneumonia?

Mr Kennedy’s pronouncements on vaccination have set off a firestorm of fury and fear. Professor Alec Ekeroma, the New Zealand-trained director of Samoa’s Health Ministry, told The Washington Post Mr Kennedy “will be directly responsible for killing thousands of children around the world by allowing preventable infectious diseases to run rampant; I don’t think it’s a legacy that should be associated with the Kennedy name”.

RFK Jr had visited and held meetings with anti-vaccine advocates in Samoa only a few months before a catastrophic measles outbreak in which 83 children were reported to have died from the preventable disease. Thousands of Samoans were infected and the island nation’s health system was overwhelmed to the point that a state of emergency was declared. A massive vaccination campaign had to be launched and red flags were placed outside the homes of unvaccinated Samoans.

“RFK Jr holds a series of false beliefs not supported by scientific evidence, and he’s always a threat to vaccines,” Dr Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Centre and a doctor at the Philadelphia Children’s Hospital, told US media outlets in November after hearing of Trump’s nomination. Dr Offit has been publicly critical of Kennedy’s vaccine stance for years.

Kennedy chairs the non-profit organisation Children’s Health Defence, a multi-million-dollar charity that sued Meta in 2020 following a ban on its advertising on Facebook and flagging “vaccine misinformation” as false. At the time, Facebook users were directed to the World Health Organisation for accurate vaccine information. In August an appeals court sided with Meta on the case.

Washington-based political correspondent Ms Olivia Nuzzi, who parted ways with New York magazine after revelations she was in a personal relationship with Kennedy, points out that many of his supporters have a deep mistrust of mainstream institutions, ranging from scientists to the media. His backers are “willing to give someone the benefit of the doubt who they perceive to be righteously challenging that power”, she said in a recent interview with the BBC. This combustible mixture of distrust and suspicion of public health advice is like a ticking bomb, and Australia is not far behind the US.

“We’ve seen an explosion of distrust since 2017,” said Michele Levine, chief executive of Australia’s Roy Morgan Research. “A rolling series of catastrophes has impacted on our trust in organisations of all kinds, and an enormous amount of distrust has grown during Covid.”

While Ms Levine describes levels of distrust in America that make it “a powder keg”, her research is picking up similar worrying trends here. “Today, with social media so pervasive, it’s really easy for negative feelings to be spread. And these things have a much longer life than you would normally expect them to have.”

Australian medical doctor and Labor MP Dr Mike Freelander is worried too. “Immunisation is a victim of its own success,” he said. “I’m getting older and I’m one of the few paediatricians who saw life before we had immunisations. We used to have epidemics of measles.” He notes the Australian community is seeing rapidly dwindling rates of immunisation.

“Governments have to play their part, and that means educating people – not forcing people, but educating people – about the importance of immunisation for these diseases, because we know they can be fatal and cause serious side effects.”

The department RFK Jr is set to control – Health and Human Services – includes the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It also includes the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services for which, controversially, Mr Trump has tapped Dr Mehmet Oz as his choice as lead. Although a qualified doctor, Dr Oz made his name as a celebrity TV physician whose pronouncements were, at times, dubious. A scientific study of his media health claims, published in the British Medical Journal, was scathing: “Approximately half of the recommendations have either no evidence or are contradicted by the best available evidence. Potential conflicts of interest are rarely addressed. The public should be sceptical about recommendations made on medical talk shows.”

Does the health system need to be run by people with medical qualifications? Dr Michael Wooldridge is both a qualified medical practitioner and was health minister in the Howard government. “I wasn’t a doctor who was in politics. I was a professional politician who happened to be medically qualified. It’s important to have a professional politician, otherwise you end up with someone who is well intentioned but never gets anything done.”

Dr Wooldridge predicts trouble ahead for RFK Jr should he try to breathe life into an anti-science agenda. “The thing you absolutely, utterly need to get anywhere is the confidence of your colleagues,” he said.

Vaccination is not the only proven public health measure in RFK’s sights. In a recent social media post he wrote, “the Trump White House will advise all US water systems to remove fluoride from public water. Fluoride is an industrial waste associated with arthritis, bone fractures, bone cancer, IQ loss, neurodevelopmental disorders, and thyroid disease.” Does such a claim stack up? What if Australia followed suit?

“I think it is really interesting, because it’s something that was discovered in America,” says Dr Matt Hopcraft, public health dental expert from the University of Melbourne. “The beauty of water fluoridation is that it helps to break down socio-economic inequalities because the water is free, everyone has access to it and they get access to that benefit without having to spend money.

“All of the evidence continues to come back that, at the levels that we use, there’s no credible evidence of harm,” Hopcraft says. “But there’s always been an anti-fluoride movement in Australia, and that seems to be growing and I think it fits within that broader scepticism of science and distrust of institutions and of science.”

RFK Jr doesn’t seem to trust the key institutions of healthcare in the US. In 2005, he wrote an article for Salon magazine claiming that “our public-health authorities knowingly allowed the pharmaceutical industry to poison an entire generation of American children, their actions arguably constitute one of the biggest scandals in the annals of American medicine”.

“People who don’t want to trust scientists, they don’t want to trust institutions, they don’t want to trust government … they would rather trust someone they know on a podcast, someone on the internet telling them something else,” Hopcraft says.

Professor Steve Wesselingh, chief executive of Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council, agrees. “I do worry about trust in science,” he said, “and I do think it is actually really important for the scientific community to spend time talking to the public about science, about the benefits of science. I think we sometimes forget to tell stories about the enormous steps and advances that science in general, and medical science in particular, has taken.”

On Kennedy, Professor Wesselingh says: “I’m fine with him having doubts about fluoride. But in the end, his job is to go and ask for the highest quality evidence on fluoride and take that on board. That’s what he should do. There’s nothing wrong with questioning it but let’s actually, in the end, be evidence-based and not allow people to get away with commentary about conspiracies.”

In Australia’s recent Covid Response Report, released in October after a year-long inquiry by Robyn Kruk AO, Professor Catherine Bennett and Dr Angela Jackson, the word “trust” is used 322 times. The report’s authors concede that “we have heard that the trust in governments … has waned as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic and the response. Rebuilding trust and maintaining it must be an immediate and ongoing priority and key to preparing effective response plans that mitigate the risk of harm and support broad health objectives.”

Public Health Association of Australia chief executive Professor Terry Slevin agrees. “Trust is a fundamental commodity when it comes to navigating health, healthcare, public health policy and certainly response to crises,” he says.

“And underpinning all of that is the way in which the public views the objectivity and expertise of the people making decisions. Can they be trusted to act purely in the interest of the population and independent of any other major influencing factor? And be prepared at times to set aside personal beliefs, to follow what is sound science and evidence-based policy and practice?”

Roy Morgan’s Levine supports Professor Slevin’s concerns. “Our nation’s view of government, its instrumentalities, its organisations, and, you know, quasi-government things is really, really low, lower than we’ve ever been able to measure,” she said, citing Roy Morgan research. “There’s a large group in Australia who now feel totally left out, they feel unlistened to and are totally distrusting … These are the people so disengaged that they don’t really want to be part of anything. They’re just angry.”

Professor Wesselingh has experienced the forces of suspicion, distrust, and disengagement with science in his role. “It’s a societal change and I think as a profession we’ve been too slow to understand that that’s happening,” he says, “and we’re still not entirely clear how we deal with it. Science underpins prosperity and it actually underpins democracy, so if we’re starting to mistrust science then that is a risk we need to understand.”

Is the news all bad? Not necessarily. Donald Trump has instructed Kennedy and Oz to “make America healthy again” with a commitment to wrestling with the “epidemic” of chronic diseases he has rightly called out as an existential threat to America’s future. These concerns align with health priorities in Australia, too. In February last year, Health Minister Mark Butler told the Royal Australian College of GPs that “all Australians will benefit … from a renewed focus on preventing chronic disease”. Indeed, Anthony Albanese used a Centre for Disease Control modelled on the American prototype as a key pitch in his 2020 election platform. “The centre would have responsibility for preventing both infectious and chronic illness, along with addressing the social and economic drivers of disease,” he said then. The CDC project received an injection of funding in the wake of the Covid Response Report.

Americans have a right to be angry. Almost 20 per cent of their country’s colossal GDP is spent on healthcare, yet compared to other high-income countries the US ranks last overall on health outcomes, including having the highest infant mortality rates and lowest life expectancy according to the Independent Commonwealth Fund in its 2024 report. American academics David Dranove and Lawton Burns, in their 2021 book Big Med, point out that the rate of preventable death in the US is more than double that of high-performing countries such as Switzerland. Indeed, life expectancy has dropped by almost three years compared to predictions made in 2019 from 78.8 to 76.1 years. Over the same period, Australians’ life expectancy increased from 82.5 to 83.4 years.

Trump also has claimed that Americans are being “mass poisoned” by “big pharma and big food”, and that federal government agencies have not responded appropriately. He almost certainly has a point. In the 2020 book Deaths of Despair, Nobel prize-winning economist the late Sir Angus Deaton pointed a withering finger at large pharmaceutical companies too. America records 81,000 deaths from opioid overdose every year, almost the same number of losses as caused by gun violence and car accidents combined. A full one third of those deaths result from prescribed painkilling medications. And for each of those 81,000 deaths there are 30 emergency department presentations that are near-misses.

Deaton revealed that pharmaceutical companies employ five lobbyists for every congress member and in 2018 spent more than $US1bn on lobbying, the largest spend of any US industry. “The organisation of the American healthcare system is a disaster,” he wrote, “because it is draining the livelihoods of Americans in order to make a rich minority richer.”

Millions of Americans experience daily the unmerciful hell the American health system can be. Despite the Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act – known colloquially as “Obamacare” – there has been little palpable improvement for many Americans in the past two decades. In 2017, almost a fifth of Americans with chronic diseases such as diabetes were unable to see doctors due to costs. Lack of private health insurance was a death sentence for many: rates of cancer survival were worse for the uninsured. Indeed, it seems people without health insurance have shorter life expectancy, according to a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 2017.

With the US health system in such a mess, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that a plan to “make America healthy again” would resonate powerfully across the nation. Is RFK Jr the right person to prosecute such a plan, though? That remains unclear.

A lawyer specialising in environmental protection, Kennedy has expressed strong views about socio-economic inequality – a major and increasing issue in the US – and has publicly stated that the gap between rich and poor in the US has become too great. There is plenty of evidence to support this view. A recent study published in the American Journal of Public Health estimated that, even with Obamacare, almost two thirds of bankruptcies in the US were related to medical bills or inability to work due to inadequate treatment. In 40 per cent of bankruptcies, medical bills were the single most common cause.

As the pandemic showed, healthcare is global and whatever we make of RFK Jr, Australia remains a world player and will have to continue to work collaboratively with the US government on health matters.

“We have always been a global leader in health,” says Dr Freelander. “We have a lot of responsibility in this area. Our immunisation programs are amongst the best in the world, and the Medicare system is acknowledged as one of the best health systems as well. So we’ve led by example, and it’s very important that we make sure our health system is fit for purpose for the 21st century, so we can continue to lead by example.”

What effect might we expect such extreme health policies to have on the Australian health system? “Absolutely none whatsoever,” says Michael Wooldridge. “I can’t think of anything from the US that truly affected Australia much, and I can probably think of a few things from Australia that have had effects the other way around.”

Terry Slevin is more cautious in his predictions. “The simple truth is that governments are the only entity, the vehicle by which regulation can occur. Now, whether that’s regulation about our food system, whether it’s about chemicals used in our industries, if we don’t get those policies right, if we don’t regulate properly, then people pay the price with serious, debilitating disease – or, in some cases, death. But the challenge exists to ensure that whoever is in government prosecutes policies in the very best interest of people in Australia and resists pressure from governments anywhere else in the world to weaken those protections.

“If circumstances occur where we don’t have faith in the regulatory regime of another nation, yet there’s an expectation that Australia will fall into line with regulatory decisions in other countries that put us at risk, it’s a fundamentally important principle that Australia has sovereign capacity and policy position that we will regulate our own environment, whether that’s to do with chemicals, whether it’s to do with medicines,” says Slevin.

“The real challenge when it comes to the circumstances in the US is to ensure that a major policy swing that may occur there doesn’t flow across the Pacific and weaken the strength of our own regulatory regime that ensures Australians have the best possible chance and live long and healthy lives.”

Dr Freelander believes we are up to the task. “We need to be very forward facing and look at the challenges that are happening as we proceed into the 21st century and make sure our system is adjustable and works to look for what the future is going to be in healthcare,” he says. “So we’ve got a lot of responsibilities. I think we can do it.”

Professor Steve Robson is one of Australia’s most highly qualified surgical specialists, researchers and teachers. He works at the Australian National University Medical School.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout