I broke the Belle Gibson story. There is so much wrong with Netflix’s portrayal

I have a pretty clear memory of how con artist Belle Gibson’s world fell apart – but it’s a bit rich that my wife’s breast cancer experience was grafted into this latest retelling.

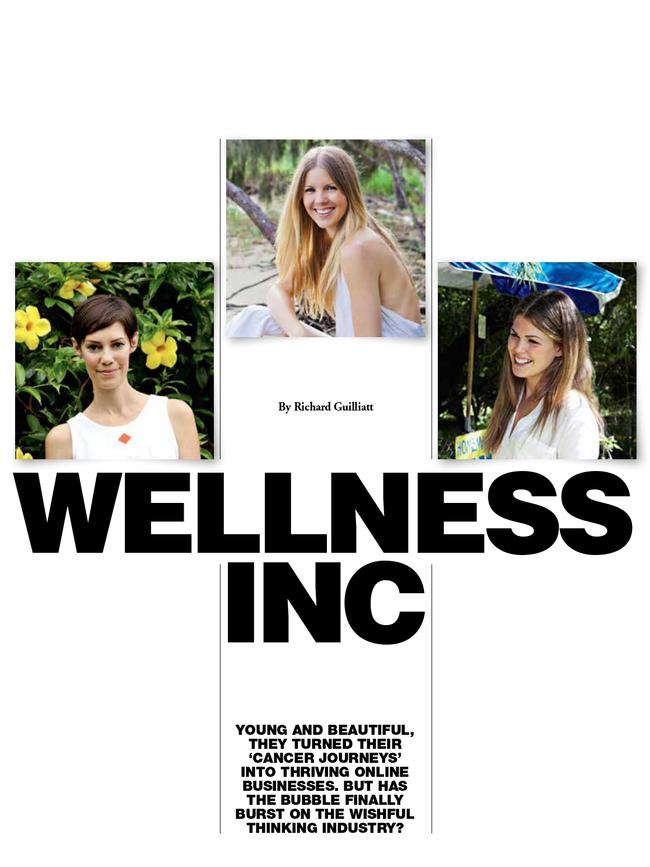

By now, millions of people have binged on Apple Cider Vinegar, Netflix’s “true-ish” drama about Australian cancer con artist Belle Gibson.

The series has generated a global publicity bonanza for Netflix and for the Nine media group, which is basking in the reflected glory the series shines on the two plucky young reporters from The Age newspaper in Melbourne who “uncovered Belle Gibson’s cancer con”, to quote The Sydney Morning Herald last week.

Those reporters, Beau Donelly and Nick Toscano, have hit the publicity trail to promote the show and their book about Gibson on which the Netflix series is based.

Their publisher pitches them as the journalists “who uncovered the details of Gibson’s lies”. In Apple Cider Vinegar, they’re shown doggedly battling against meddlesome defamation lawyers and uncaring editors before triumphantly publishing the story that unmasks Gibson as a phony brain cancer survivor.

It’s strange to see historical events you know well told through the lens of a “true-ish” television series. I have a pretty clear memory of how the Gibson cancer scam unravelled, back in the distant mists of 2015, and I’d swear it wasn’t the work of two young reporters at The Age in Melbourne but one middle-aged reporter at The Australian in Sydney. Actually, I’m pretty sure that guy was me because I recall a boozy night at the Walkley Awards for outstanding journalism, where I was shortlisted for Scoop of the Year for my work in exposing Gibson’s long history of medical mendacity.

The lies of Belle Gibson and Apple Cider Vinegar

Of course, complaining about the historical accuracy of a historical drama series could be the perfect definition of futility. And after watching all six episodes of Netflix’s version of the Gibson story, I probably should be thankful for being written out of it, given the way actual people and events have been warped and reinvented to fit this over-caffeinated, pop-soundtracked caricature of Gibson’s life and exploits.

Apple Cider Vinegar may be the perfect encapsulation of our hyper-saturated media environment – a drama about a real-life compulsive liar, told with little regard for the truth, and featuring actors who occasionally turn to camera to admit you’re being misled. “This is a true story, based on a lie,” one character says at the beginning of episode three. “Some names have been changed and characters have been invented, which is … Do you care? Should you?” I’m going to say yes to that question, unfashionable as that may be.

Netflix has plenty of form when it comes to making fictional fodder out of living people: The Crown misleadingly suggested Prince Philip was estranged from his mother and partially responsible for his sister’s death in a plane crash, and Russian chess champion Nona Gaprindashvili won a defamation settlement after The Queen’s Gambit falsely stated she had never faced a male opponent.

But Apple Cider Vinegar is a story based on living people dealing with real tragedy and mental health issues, a fact that doesn’t seem to have troubled the producers and scriptwriters.

The plot device that propels this series portrays Gibson locked in bitchy rivalry with a Queensland “wellness” blogger, Milla Blake. The two women have amassed followings on social media by sharing their “cancer journeys”, but while Gibson is faking her brain tumour, Blake actually does have a rare form of sarcoma that can be cured only by total amputation of her arm and shoulder. She has opted to abandon treatment in favour of coffee enemas and juices, along the way influencing her mother to attempt the same “cure” for her breast cancer.

These details mirror precisely the sad story of the Australian “wellness warrior” Jess Ainscough and her mother Sharyn, whom I interviewed for a cover story in The Weekend Australian Magazine in late 2012. I remember this story vividly because it was my first foray into the world of wellness and because Jess Ainscough and her mother struck me as two lovely women making a terrible mistake.

I empathised with their dilemmas because my wife had been diagnosed with breast cancer and we knew what it was like to be bombarded with all manner of downloaded folk medicine advice. At the same time, Jess Ainscough’s online denunciations of Western medicine and her claims that she had cured herself seemed dangerously misguided. Writing that story was agonisingly difficult.

Sharyn Ainscough died 13 months later and by late 2014 Jess Ainscough had become seriously ill and returned to conventional treatment – too late because she died in early 2015. Again, this is mirrored in Apple Cider Vinegar. But Jess Ainscough certainly never engaged in a deathbed plot to “destroy” Gibson after discovering she was a fraud, and Netflix’s decision to turn her tragedy into a Mean Girls cliche of female backbiting has deeply upset those who knew and loved her.

This week Ainscough’s former fiance, Tallon Pamenter, released a statement describing Apple Cider Vinegar as falsified and offensive. Viewers of the series, meanwhile, now are posting negative comments about Ainscough on her Instagram page, which lives on despite her death.

It’s true that Gibson’s downfall more or less coincided with Jess Ainscough’s death, but the actual “true story” of why that happened is more complicated, as told in the British documentary Instagram’s Worst Con Artist, which Netflix is scheduled to release next week.

This may prove confusing to many people who watched the fictional series because the documentary hardly mentions the The Age newspaper and focuses instead on my Walkley-shortlisted expose of Gibson for The Australian in early 2015. For what it’s worth, here’s the brief synopsis of how those stories came about.

In late 2014, while researching a follow-up story about Jess Ainscough’s declining health, I stumbled across Gibson’s Instagram page and suspected immediately that she must be a fraud. Over two months of investigating, I consulted cancer experts and dug into Gibson’s past, uncovering some of the wildly improbable stories of medical survival she had been posting online since her teens. I learned that people close to her knew her stories were false, that she had lied about her age and that Penguin Books had never checked her bona fides before signing her up for her book The Whole Pantry. I persuaded Gibson to grant me an interview, during which she tried to walk back many of her cancer claims.

The Australian published the first of these reports on March 10, 2015, spurred into print by a small story on page 4 of The Age that revealed that Gibson had failed to donate money she raised for various charities. In the wake of our revelations about her false medical claims, Gibson went to ground and began deleting her social media posts, confirming her guilt.

By week’s end, her business was all but dead.

The Australian’s reporting is not mentioned in Apple Cider Vinegar, perhaps because it’s barely acknowledged in the book that The Age team later wrote, which the show is adapted from. C’est la vie – I can understand why the scriptwriters weren’t keen on a dramatic conclusion in which their intrepid young journos wake up to discover they’ve been scooped by the opposition. Still, it seems a bit rich that my wife’s breast cancer experience was grafted on to the storyline of the fictional Age journalist “Justin”, given that we didn’t even score an invitation to the premiere.

The biggest fiction in Apple Cider Vinegar, though, is its portrayal of Gibson. Anyone who met and interviewed Gibson – a relatively small circle that doesn’t include The Age team – could tell you that she carried herself with an air of dreamy, airy fragility. Her voice was so soft and quavery you had to lean in to catch what she was saying. Every sentence seemed to end on a question mark, in the manner of a hesitant adolescent.

To some extent this was a persona Gibson projected, for there is no doubt that she did do many of the terrible things depicted in the series. She lied about having cancer; she made money from peddling the dangerous notion that brain tumours could be cured with juices and organic food; she pretended to collapse at her four-year-old son’s birthday party; she exploited the family of a young boy with brain cancer for her own publicity; she raised money for charity and kept it for herself. Clearly she was a pathological liar, but Apple Cider Vinegar presents all this as the work of a shrewd, conniving plotter when in reality Gibson was the clumsiest of con artists.

Digging into Gibson’s past, one thing that shocked me was how flagrantly obvious her lies were and how poorly she covered her tracks. She had tried to delete her early social media history but forgot about the most incriminating evidence: a series of posts she had written on an online skateboarding forum as a 17-year-old, in which she claimed to be recovering in a Perth hospital after she had died and been resuscitated during heart surgery. I found those posts and others with her earliest claims of a brain tumour because she had used her full name on the forum. Even some of the teenagers on the site mocked her.

Gibson had been spinning such fantasies since early adolescence and many of her old acquaintances from Queensland knew she had stolen her brain tumour story from the actual death of their friend Rome Torti, a skate photographer who had chronicled his treatment on social media.

A smart con artist might have been less obvious or pretended to be suffering a slow-growing cancer such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but instead Gibson went for the big kahuna – stage four blastoma, a brain cancer so deadly that survival is low even with treatment.

Even that wasn’t enough, however, because in July 2014 – after she had won her contracts for a book with Penguin and a watch app with Apple – she made the absurd public announcement that she now had four additional cancers, in her liver, spleen, blood and uterus.

In Apple Cider Vinegar this announcement is portrayed as a snap decision Gibson made while attempting to confess online as her scam unravelled. In reality, it seems to have been a symptom of her complete disconnection from reality and her insatiable need for sympathy, attention and the “likes” that keep a social media business afloat. Sitting across from her in a Melbourne cafe seven months later, I remember feeling a twinge of sympathy as she lamely tried to talk her way out of this outrageous fabrication by blaming the extra cancer diagnoses on a “doctor” she couldn’t name who used a machine she couldn’t properly describe.

The walls were closing in on Gibson at that point and she clearly had no exit strategy.

Two of her friends, Chanelle McAuliffe and Jarrod Briffa, had already confronted her and demanded she publicly confess. In the wake of this newspaper’s stories, her US publisher immediately suspended publication of her book and her social media followers went into meltdown.

A month later, under the guidance of a crisis manager, she granted an interview to The Australian Women’s Weekly in which she finally confessed that “none of it is true”. The journalist who wrote that story, Clair Weaver, painted a nuanced portrait of Gibson as someone likely in the grip of a psychological disorder that compelled her to fantasise and fabricate. As we’re discovering, through countless podcasts and documentaries such as Sweet Bobby, Inventing Anna and Snowball, there’s a lot of it out there.

Gibson grew up with a hypochondriac mother, an absent father and a dysfunctional home life that she fled in her early teens. It’s hardly making an excuse for her behaviour to say she seems to be a damaged person. Apple Cider Vinegar is not much interested in that, presenting her instead as an immoral schemer and negligent mother, so heartless that she collapses into giggles when told her father-in-law has suffered a stroke.

I doubt Gibson will watch this series, but it’s not hard to see the horrible irony of the way this fantasist’s life has been re-fantasised, or wonder what impact it might have on her and her now-teenage son.

Richard Guilliatt is a former senior journalist with The Weekend Australian Magazine.