England and Australia have diametrically opposed vaping laws. Only one is proving effective

England encouraged smokers to switch to vapes and even gave them to pregnant women at antenatal clinics. Now it’s looking to Australia’s tough stance as medics say the English policy has been a disaster.

It was the bold public health claim that formed the foundation of a permissive national strategy on vapes. Five years ago, Public Health England declared e-cigarettes to be 95 per cent less harmful than tobacco smoking and encouraged smokers to switch to the devices. It’s an approach that is diametrically opposed to Australia’s tough stance on making virtually all vapes illegal.

As evidence starts to emerge on vaping trends as well as health harms, the real-world consequences of Australia and England’s contrasting policy approaches are beginning to become clear. Many doctors in the UK describe the officially endorsed policy in England of vaping as a stop-smoking tool – vapes were even distributed by the National Health Service to pregnant women at antenatal clinics – as a catastrophe for the country and a lesson to the rest of the world.

“I think it’s incomprehensible what has played out,” says Professor Martin McKee, medical director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “From the very earliest days, when it was clear that e-cigarettes were being promoted heavily by some groups in the UK, some of us were extremely concerned, and our concerns have been completely vindicated.”

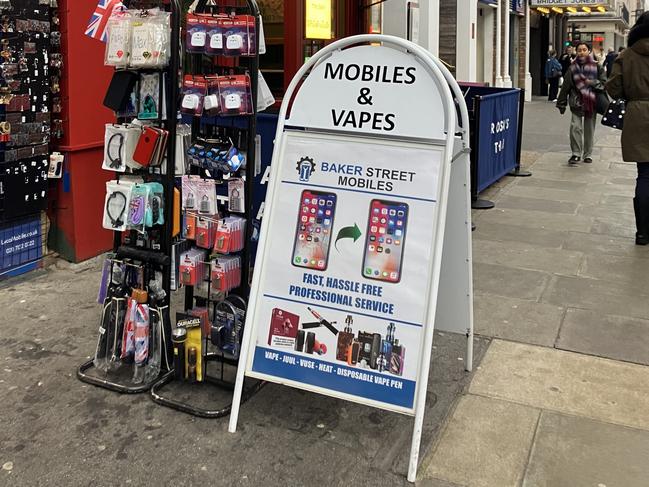

The strategy of regulation that was pushed primarily by addiction medicine advocates in England and was supported by leading medical groups has in fact not resulted in a regulated market. Illegal vapes have flooded England. Shops exclusively devoted to selling the devices have popped up with names such as Vape CBD, and pop-up vendors sell a wide array of illegally imported vapes all over London.

And the official health messages downplaying the harms of vaping that were aimed at smokers to encourage them to switch have resulted in a widespread take-up of vaping among those who had never smoked before, most concerningly teenagers. Dangerous “dual use” of vapes and cigarettes is now also common among smokers.

A paper recently published in the Lancet found one million people in the UK now vape despite never having been regular smokers – a seven-fold increase in just three years. In 2021, one in 200 people who had never smoked – about 133,000 people – were vapers in the UK. That number is now one in 28.

Among all people aged over 16, one in 10, or more than five million people, use e-cigarettes, according to the UK’s Office for National Statistics. Vaping rates among those aged 16 to 24 are now almost 16 per cent, and have doubled in five years. Most of those young people had never previously smoked.

“The e-cigarette optimist view is based on limited evidence, and we do not consider the ‘95 per cent less harmful than smoking’ figure as being at all robust,” says Sheila Duffy, the chief executive of Action on Smoking and Health Scotland. “Continuing to cite the figure is unwise due to recent emerging evidence of harms.

“The evidence is clearly stacking up in favour of a precautionary approach, which Scotland has taken, and absolutely not in favour of opening up to recreational, largely untested and lightly controlled vaping products – that is, not recommending them as if they were on a par with Nicotine Replacement Therapies that are available on medicinal prescription.

“Vapes have got a massive marketing kick from the companies and from some health representatives but the on-ramp to addiction, particularly amongst children and young people, can clearly be seen.”

Even smokers themselves think the health messages that have been issued in England are dubious. On the streets of Mayfair, The Australian catches up with 32-year-old Sham, who is smoking heated tobacco. He never believed public health messaging that vaping was only 5 per cent as harmful as cigarettes.

“Vapes are not so much less harmful than smoking,” he says. “There’s so many flavourings and chemicals.

“I don’t like it, I genuinely felt like my heart was having palpitations when I vaped. You know, they say one vape is like smoking about 200 cigarettes. You sit at home, you sit in bed vaping non-stop.

“It’s odd here now, seeing kids in school uniform vaping.”

Public Health England is a respected statutory body that examines evidence on health matters and its endorsement of vaping as much less harmful than smoking prompted local districts in the UK to fund stop-smoking clinics run out of pharmacies distributing e-cigarettes to tobacco addicts. Vapes could also be sold at supermarkets. However, the policy of regulation of e-cigarettes did not stop the emergence of a massive black market of highly flavoured, very high nicotine vapes.

Vaping rates in young people have spiked so alarmingly in England that Keir Starmer’s Labor government is now planning to follow Australia’s world-first legislation and ban disposable vapes. The UK government will also introduce a licensing scheme for the retail sale of tobacco and vapes and is set to introduce excise taxes on vapes for the first time.

Medical groups including the British Medical Association have now reversed their previous support for England’s pro-regulatory vaping policy. Apart from growing indications that vaping has not helped smokers quit nicotine, there is now also evidence that vaping is as bad for cardiovascular health as smoking. It is also likely to be carcinogenic, although not to the same extent as tobacco smoking.

On top of this, doctors who have become aware of the origins of the “95 per cent safer than smoking” claim have become increasingly alarmed that England’s vaping policy was influenced by the tobacco industry. That’s because several authors of the study that first published that claim – which was a figure based on their own consensus – were linked to a company called Health Diplomats which promotes “harm reduction policies” including vaping. South African doctor and former World Medical Association secretary-general Delon Human is the CEO and president of Health Diplomats. The consultancy was in partnership with another entity founded by Human called Nicoventures, which was a subsidiary of British American Tobacco.

Health Diplomats was added to the federal lobbyist register in Australia two years ago by a former Nationals politician with links to the tobacco industry, although there is no evidence the consultancy has attempted to actively influence Australia’s policy.

Many in England are now looking to the early evidence that although a massive black market in vapes continues to thrive, Australia’s tough laws on vaping are beginning to succeed in reducing youth take-up of the habit.

The latest data from the Cancer Council’s Generation Vape study – which has assessed vaping incidence since Australia’s legislation banning the sale and import of the devices was passed – found the proportion of “never-vapers” among 14 to 17-year-olds rose from 82 per cent to 87.5 per cent. That was the highest rate recorded since 2022. Vape purchases declined from 36 per cent to 26.8 per cent. There was also a reduction in smoking rates in this age group, with the proportion of adolescents who have never smoked rising to 94 per cent.

“Australia has been fortunate in having a number of very effective and very, very competent, highly skilled public health people who have been able to look at the evidence and see the big picture, and the policy has therefore been much more effective,” says Professor McKee. “You’ve got a strong tobacco control community there and have had for a long time. And I suppose that may be the biggest difference – that Australia’s tobacco control community is much more broadly based, and it looks at children, cardiovascular disease, lung disease, addiction, and commercial determinants.

“You’ve got people who have a broad perspective. Whereas in the UK, there’s been individuals who are very narrowly focused on either coming from a narcotic addiction perspective or chest medicine perspective.

“That doesn’t lead you to think about the implications for children, for cardiovascular disease, for the environmental hazards of disposal types, all those other things. So it’s a very narrow focus, whereas, I think in Australia, you’ve just had a much broader range of expertise, and also expertise that is plugged much better into the international debate.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout