Are teens worried about social media bans? Let’s text them to find out

Should we be concerned about a cataclysmic long-term impact on the cognitive functioning of doomscrollers? Try tearing your kids away from the screen to ask what they think.

My 16-year-old daughter recently spent an afternoon shopping downtown with a girlfriend.

I met her at a designated time for pick-up. She was waiting in an arcade, sitting on the ground with her back to a shop window beside her friend.

Both young women were on their mobile phones when I arrived.

On the drive home, I asked her what they were looking at on their phones back there in the arcade.

“We were texting,” she said.

“To whom?”

“Each other,” she replied matter-of-factly.

Call me old-fashioned, hopelessly out of touch and straight from the Palaeolithic Age but I would have expected, in a civilised world, that two good friends sitting literally shoulder to shoulder, so close they were able to take in a whiff of each other’s Billie Eilish Eau de Parfum (vanilla, cocoa, gentle spices), might communicate directly with those things that we call mouths, using something we call language.

Like many parents I have almost given up on devising ways and means of prising my children off their phones and iPads. Nor do I want to face the reality that from time immemorial children have modelled their behaviour on that of their parents. I can hardly issue orders to my kids as the Device Tsar and then hop straight onto my own phone and scroll away.

It’s no surprise that this genuine epidemic – infecting adults and children alike – has triggered new words that have entered the language like doomscrolling, which to the fatuous, including myself, vaguely sounds like a movie about a Marvel villain and dank Egyptian tombs.

Alas, doomscrolling is precisely as it sounds – fiddling about relentlessly on your phone and absorbing all the bad news the planet has to offer until either the world ends or you do, or both.

Hats off to the Australian parliament for last week passing world-first legislation banning children under 16 from holding accounts on social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, X and Reddit. A failure by platforms to enforce the law may result in fines of $50m. The companies have a year to sort out the practicalities of the ban.

It spells doom for doomscrolling. Or does it?

Specialist scientific studies are coming up with wildly contradictory results when it comes to the physical and mental impact of doomscrolling.

A recent study published in the Journal of Computers in Human Behaviour Reports unequivocally concluded that doomscrolling had become a “source of vicarious trauma”.

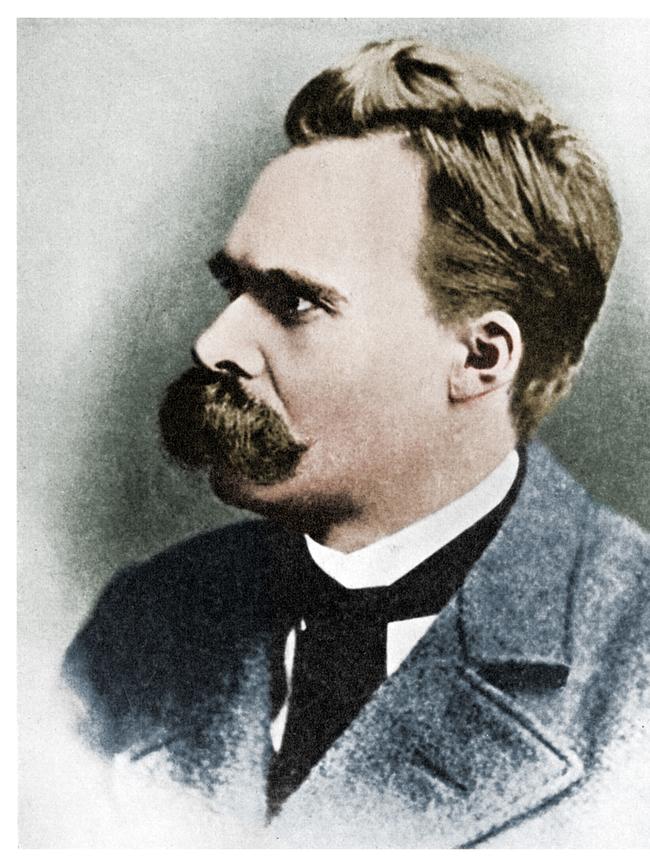

The study’s survey of 800 students from – interestingly – Iran and the US – reportedly found that too much exposure to dark and disturbing news was linked to the students’ thoughts on “life being fragile and limited” and that humans were “fundamentally alone”. (Oh, what fun Friedrich Nietzsche would have had with a smart phone.)

Dr Joanna Orlando, digital behaviour expert at the University of Western Sydney, reportedly commented on the findings as “not surprising”, and added that the long-term impact of doomscrolling on mental health was like being in a room where “people are continuously shouting at you”.

The New Yorker magazine recently published a report titled Has Social Media Fuelled a Teen-Suicide Crisis?

It’s a terrifying read. It quoted several studies that concluded that rates of depression among teenagers had increased alongside the demographic’s increased exposure over recent years to social media and all the digital treats smart phones have to offer.

The report said a John Hopkins University study found that spending more than three hours per day online (if you think that’s a lot, check your own daily Screen Time percentage) saw adolescents “internalise” problems, which in turn made it more difficult for them to cope with anxiety and depression.

In the litigation-crazy US, lawsuits from aggrieved parents against social media companies are flying. Given profits from teenage users are in the billions of dollars, why would these companies rush to implement safeguards? While Australia’s recent legislation was applauded around the world, there were naysayers in equal measure.

Now two academics from the University of NSW have weighed into the digital mix, countering the doom in doomscrolling.

The work of Dr Poppy Watson, adjunct lecturer with UNSW’s School of Psychology, and Dr Sophie Li, a clinical psychologist and research fellow with the UNSW-affiliated Black Dog Institute, seems to suggest that while concerns about digital technology are warranted and need to be explored, the evidence is not necessarily pointing towards a cataclysmic long-term impact on the cognitive functioning of doomscrollers.

Dr Watson: “This isn’t to rule out that there are negative effects from overexposure to digital devices and their content, but so far, the research isn’t showing that causal link.”

Dr Li and her colleagues are part of a huge study of more than 6000 Australian teenagers, tracking over time their screen use alongside their mental health. While the research is yet to be published and is under review, the study may fly in the face of others around the world.

Dr Li: “We replicated all the previous studies that showed there’s definitely a correlation where more screen time is associated with more depression and more anxiety. But when we looked at depression and anxiety 12 months later, we either saw a reduction in the size of the correlation to the point where it’s almost negligible or no association at all, providing not a great deal of evidence that screen time is leading to subsequent reductions in mental health.”

The UNSW study also poses a sensible question: is this debate simply a reaction to new technology, just as the printing press, radio, television and other historical watershed technology moments threw their own respective societies into a tizz?

“With online content we’re in uncharted territory,” said Dr Watson.

Does any of this concern our digitally obsessed children who were born into this technology and have known nothing else? When Australia’s new bans take effect, how quickly will this tech-savvy generation work out how to circumvent the ban?

Is this the end of the world for pre-teen social media junkies, or will it simply spawn a new generation of digital con artists, taking on government-mandated bans on their screentime freedoms as if they were just new online games to be conquered?

I’ll text my daughter, who’s in the next room, and ask her.

But I already know her answer.

Meh.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout