Why VCs are still failing to make the (pay) grade

The university employee union is complaining about vice-chancellors’ pay – it is high-rotation rhetoric on the comrades’ playlist of endless outrage.

But it keeps coming up because universities make a mess of the case for vice-chancellors’ cash – that, and because for years and years many, many managements have stuffed up staff superannuation and breached their own pay agreements.

According to the union, numerous universities pay vice-chancellors more than the Prime Minister. Certainly there are $1m-plus packets for many metropolitan VCs. Pay is more modest in the regions, where some vice-chancellors subsist on $600,000 to $800,000. Even so, comparisons all over are odious for university councils that approve pay.

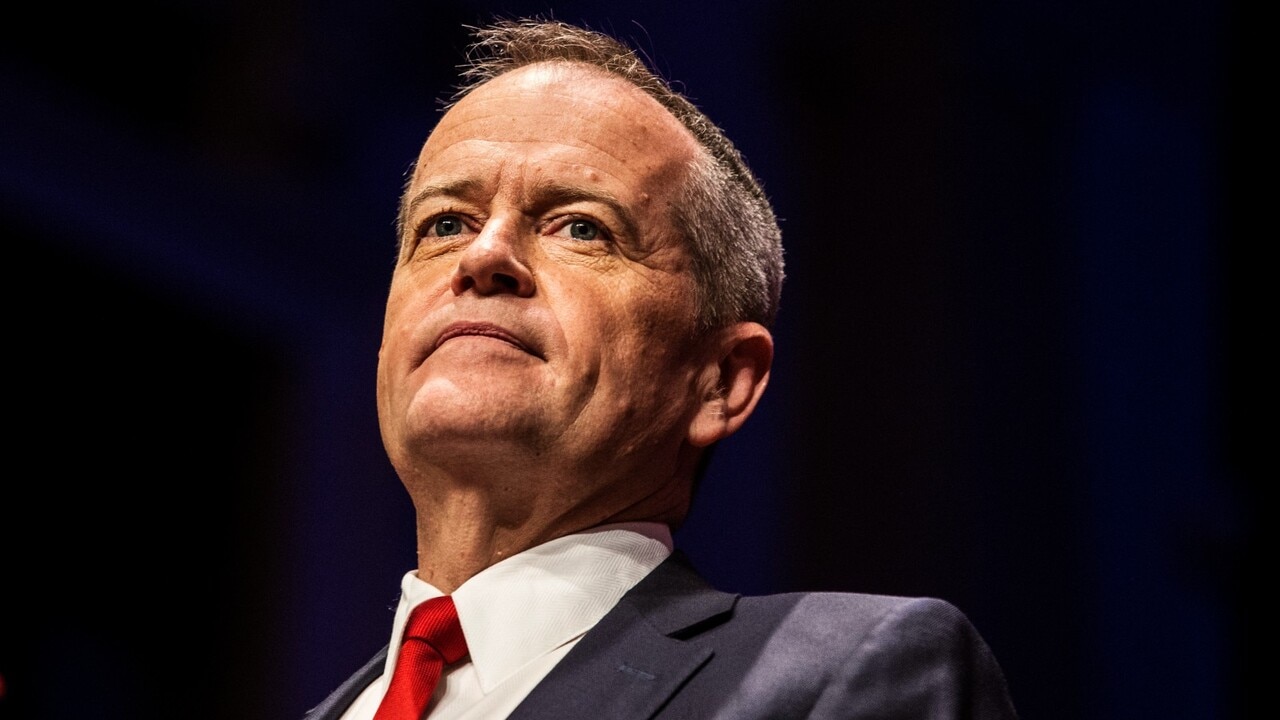

As outgoing minister for the $43bn a year National Disability Insurance Scheme Bill Shorten made $400,000. Shorten starts as vice-chancellor of the University of Canberra next year for less than his predecessor’s $1m-plus, but he still will be paid a comparatively hefty sum to run an institution with $386m income last year – not much more than a rounding error from where he comes from.

The argument universities use is that they pay market rates to get the best talent to run immensely complex organisations, with public service cultures and private sector KPIs. But there have always been, indeed are, utterly hopeless vice-chancellors paid at grades way above their ability. It happens because pay packets are set by university governing boards that are generous to a fault on executive salaries.

There are common reasons for this. Vanity is one, as if a vice-chancellor’s pay is a sign of a university’s status. Another is the assumption that money is the only way to attract top talent – a curious argument to run for institutions that bang on about community service.

But the big one is that university councils are not like boards of public companies that exist to safeguard shareholders and are obliged by the market’s judgment of their share price to remove failing managements.

State acts of parliament govern universities (ex Australian National University) and they generally permit councils to decide what is best for their institutions.

The NTEU argues increasing staff and student membership of councils will fix this, although that assumes a workers’ soviet is a good idea. Even so, the union has a point when it complains that universities pay their executives plenty but stuff up other people’s pay.

One university-system failing, now less common than a few years back, is not paying staff all their superannuation. Another that still occurs is messing up pay rates, often for casual staff paid variable hourly rates. The union calls this wage theft and there is a case alleging this in the court system, but in general it is due to incompetence rather malfeasance, with administrators not understanding the employment terms and conditions their managements signed on to.

Whatever the reasons, it drives the Fair Work Ombudsman nuts. It states the university sector is a “regulatory priority” on pay.

The contrast is stark. But while universities try to apologise their way out of being held accountable for underpaying people the University Chancellors Council, a flash name for chairpersons of their boards, has had a go at addressing the top management pay perception problem. It has a weasel-worded voluntary code on university management, including setting pay. Remuneration “needs to be fair to the individual and the institution” and “takes into account responsibility, scale and complexity to ensure individuals and appropriately rewarded for the jobs they do”. Which can mean whatever the headhunters recruiting a new vice-chancellor recommend it should mean.

Shorten obviously gets this is not a good look. The problem is that gestures do not always impress. University of Sydney vice-chancellor Mark Scott took a 30 per cent cut on what his predecessor Michael Spence made when he started. Four years later Scott’s pay is back over $1m. ANU vice-chancellor Genevieve Bell has just reduced her pay by 10 per cent; the university also asked staff to give up a scheduled increase, (they declined). However Bell still makes more than $1m.

The problem for university councils is that the two pay perception issues – too much at the top, not what people are owed at the bottom – are now on the political agenda.

In April, state and national education ministers agreed to take advice on universities’ governance, including “a rigorous and transparent process for developing remuneration policies and settings for senior university staff, with consideration given to comparable scale and complexity public sector entities, and ensure remuneration policies and packages are publicly reported”.

Federal Education Minister Jason Clare did not mention this in a speech to chancellors last month, but he certainly raised other people’s pay – calling for ways “staff can have confidence that they will not be underpaid for the important work they do”. And in a message the NTEU will love, he mentioned “making sure governing bodies have the right expertise, including in the business of running universities”.

Too right this would be an intrusion on university autonomy, but it is one the university councils have brought on themselves.

University managements are not their own worst enemies while the National Tertiary Education Union is around. But bad or no cases for high vice-chancellor pay do not help, especially at the many universities where there are cases of staff not paid the agreed rate for their job.