Universities ordered to combat gender-based violence with billion-dollar safety plan

The tertiary education watchdog wants security guards to wear body cameras to deter ‘external actors’ as universities prepare for billion-dollar safety rules.

Universities are facing a billion-dollar bill to pay for new student safety rules over the next decade, as the tertiary education watchdog seeks greater on-campus surveillance.

Official costings reveal universities will bear 90 per cent of the $1.2bn cost of the Albanese government’s freshly-legislated national higher education code to prevent and respond to gender-based violence on campus and in student accommodation.

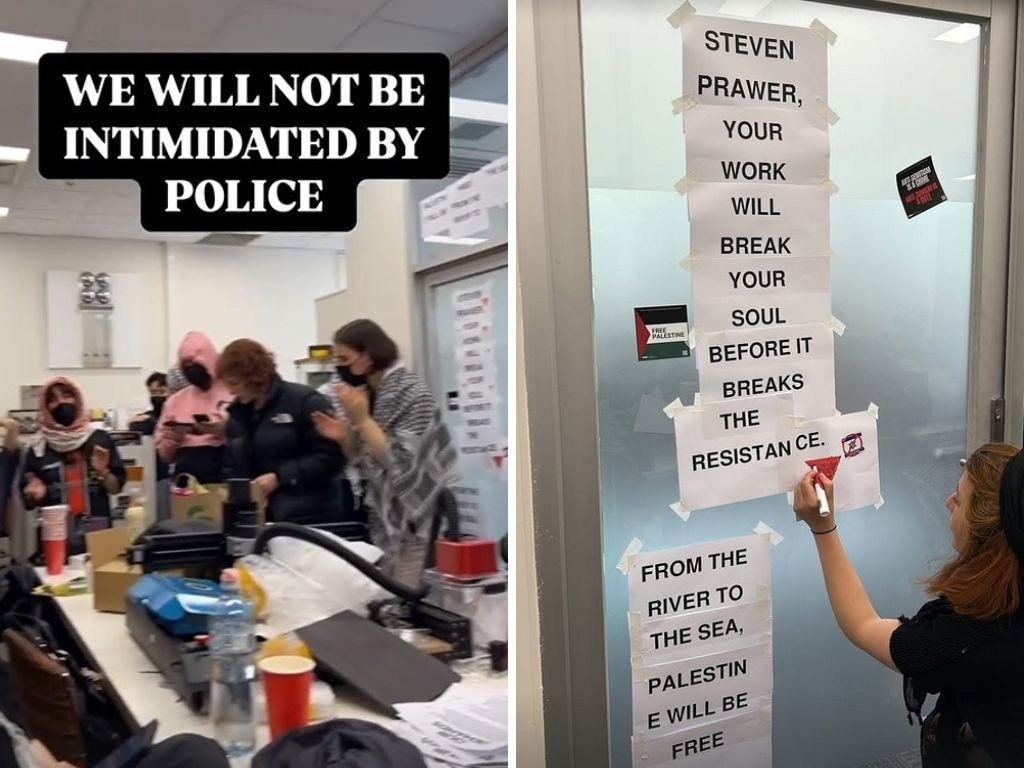

As universities scramble to prepare for the code to take force next month, the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency has called for security guards to wear body cameras to discourage “external actors’’ from stirring up trouble on campus.

Citing the disruptive encampments and protests over the Gaza war last year, TEQSA has warned that “outside agitators’’ are challenging for universities to manage.

Universities should consider deploying closed circuit television across campus, and use electronic identification cards for staff and students to access private offices and laboratories, TEQSA states in a sector update.

“Consider the necessity and effectiveness of security personnel wearing body-worn cameras,’’ it states.

“There is evidence from some providers that body-worn cameras may reassure the provider’s community, modify behaviour and deter anti-social behaviour when used appropriately.’’

TEQSA also warns that some outsiders may “provoke” staff and students to break university rules.

“External actors may film students and staff in breach of their codes of conduct and then report the breach to the provider and the media, manipulating the situation and its presentation to promote an ideological agenda,” it states.

“Providers are expected to balance student and staff freedoms to express ideas and political views without fear of reprisal against genuine concerns about safety and harm.’’

The crackdown on outside agitators coincides with a mandatory code, to start on January 1, forcing universities to hire staff to deal with reports of sexual harassment and assaults on campus.

Universities must assign different support staff to assist the alleged victim, as well as the alleged perpetrator.

All formal reports of gender-based violence – ranging from rape to verbal abuse and technology – must be investigated and finalised within 45 days of a complaint.

“For disclosers and respondents, HEPs (higher education providers) must assign staff with relevant expertise and experience to develop tailored support plans,’’ the official cost-benefit analysis by Deloitte Access Economics states.

“Where a (provider) identifies that it does not have staff with the necessary expertise and experience to carry out an investigation or determine a disciplinary proceeding, (it) must engage an external person with the requisite expertise.

“The code requires that (providers) ensure these staff members undertake training once every three years.’’

Universities must also “prioritise access to translation and interpreter services’’ when needed or requested.

They must “implement any measures necessary to ensure the safety of the discloser’’, and undertake ongoing risk assessments.

Academic or work adjustments for students or staff who are victims of gender-based violence must also be considered.

“Safety measures must be taken regardless of whether an investigation occurs,’’ the document states.

Universities must also report to the Education Department every year on the number of violence allegations against staff and students, broken down by sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, year of birth, ethnicity, religion, country of birth, language spoken at home, the need for an interpreter, and Indigenous and disability status.

The Deloitte analysis, commissioned by the federal Education Department, states that the benefits will equal the cost of implementation if the code prevents just 1.2 per cent of physical and sexual assault cases on campus – equivalent to 414 cases per year.

The benefits are based on the average $260,000 claim for psychological injury – including pain and suffering, medical costs and lost income – through WorkCover compensation claims.

The Education Department’s impact analysis of the code estimates the regulations will cost $173.2m every year.

“Providers will bear the majority of the costs and operational responsibilities of the National Code,’’ it states.

“These include costs related to compliance, updating systems and processes, staff training, and resource allocation.

“While the initial and ongoing costs to providers are significant, providers will also benefit through … a reduction of GBV (gender-based violence) and improvement of safety for students and staff, enhanced institutional reputation, improved student attraction and retention, and the potential to lead broader social change in relation to GBV.’’

The document estimates specialised staff will cost universities $175 per hour, including on-costs and overheads, with $80 an hour for other staff.

It predicts that 15 per cent of all university staff will be roped into helping implement the code in the first year, with 10 per cent of staff involved in subsequent years.

Universities will be required to establish internal support services, as well as referral pathways to police or sexual assault services.

The National Student Safety Survey of 44,000 students, commissioned by Universities Australia and carried out by the Social Research Centre in 2021, found that one in six had experienced sexual harassment and one in 20 had suffered sexual assault since starting university.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout