As President Joe Biden said in announcing the strike, Zawahiri’s death offered closure for families who lost loved ones in the attacks of September 11, 2001. Zawahiri was a founding member of al-Qa’ida and one of the key thinkers behind its declaration of war on the US. His vision drove the decision to launch so-called spectacular attacks such as 9/11, which dramatically escalated the terrorism threat, raising what had once been seen as a law enforcement and intelligence problem to the level of large-scale warfare and regime change.

Zawahiri’s strategic vision led to the largest and deadliest terrorist attack in history. It provoked the war in Afghanistan, launched the war on terror and triggered the catastrophic invasion of Iraq. The worldwide “forever wars” touched off by 9/11 contributed to the decline of the US from its post-Cold War pinnacle as the sole global superpower. Indeed, in part, today’s diminished America is a result of two decades spent inconclusively chasing Zawahiri and those he inspired.

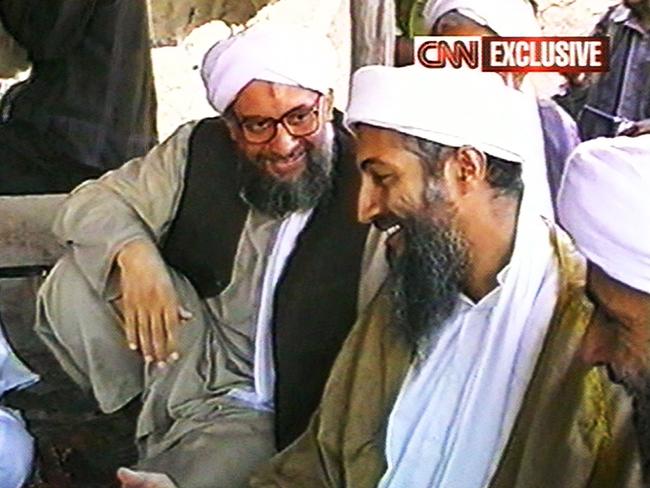

In this sense, Zawahiri’s death ties up one of the loose ends from the early war on terror – among the al-Qa’ida leaders responsible for 9/11, Zawahiri was one of the last left alive. The 9/11 attackers themselves, of course, died on the scene. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, operational planner for the attacks, was captured in 2003 and remains in detention at Guantanamo Bay. Osama bin Laden was killed in 2011.

Only Saif el-Adel – the former Egyptian special forces officer who authored al-Qa’ida’s military manual and masterminded several significant attacks – remains at large, probably in Iran.

For all its tactical precision – two early-morning Hellfire missiles, dropped from a high-altitude drone, struck the balcony where Zawahiri prayed and watched the sunrise over Kabul, killing him while barely damaging the building – the strike underlines the strategic impotence of over-the-horizon counter-terrorism.

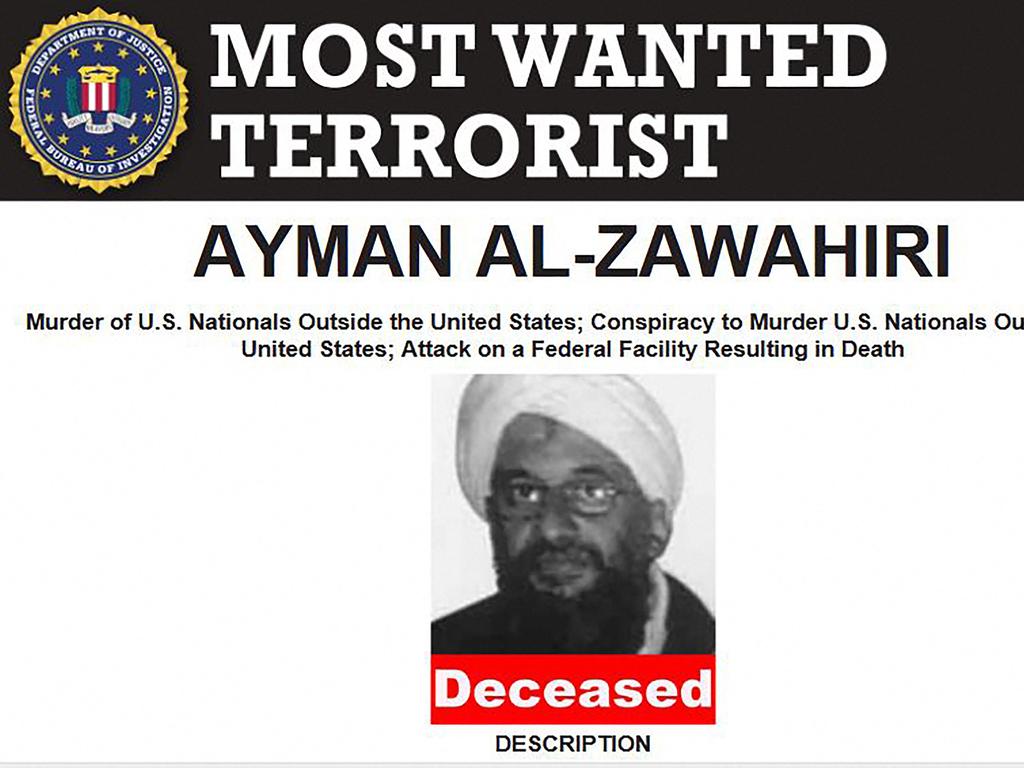

Zawahiri was symbolically important but operationally the 71-year-old was a figurehead. The old man’s terrorist career began four decades ago with the 1981 assassination of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat. He had long since ceased to plan or conduct operations, and a new generation of al-Qa’ida leaders had risen to prominence.

These include Abdel Rahman al-Maghrebi, Zawahiri’s son-in-law; Yazid Mebrak, who leads al-Qa’ida in northwest Africa; Ahmed Diriye, the emir of al-Shabab, al-Qa’ida’s branch in East Africa; and Khalid Batarfi, head of al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula.

Any of these might be a contender to replace Zawahiri, but the appointment would be symbolic, not substantive, since the centralised, hierarchical organisation Zawahiri founded no longer exists. Regional leaders such as Mebrak or Diriye, local cells led by jihadists no outsider has ever heard of, and atomised, self-recruited individuals are more important drivers of today’s terrorist threat than are symbolic figureheads such as Zawahiri.

More broadly, Islamic State – a breakaway faction that rejected Zawahiri’s succession as head of al-Qa’ida after US forces killed bin Laden in May 2011 – is the leading jihadist threat today. Islamic State is more violent and radical than the original al-Qa’ida and sits behind the fastest growing terrorist groups globally. All or most of these are in Africa and the Middle East, though Islamic State also has influence in Southeast Asia and a below-the-radar presence in Western societies.

Strategically, then, even as the US knocks out the last of the al-Qa’ida old guard, the organisation and the threat have moved on. At the grand-strategic level, the forever wars launched after 9/11 have done little to reduce the danger they were designed to address.

Rather, the war on terror spread the terrorist threat worldwide, created larger, newer and more radical groups, destabilised entire societies making them more vulnerable to terrorist influence, and weakened the moral authority and military credibility of the US and its allies.

More insidiously, techniques of targeting, surveillance, entrapment, financial control and suspension of individual liberties that were pioneered during the supposedly temporary emergency of the war on terrorism have become normalised, permanent, routine tools of government. They are increasingly applied against internal political opponents and dissenters within our own societies, irrespective of ideology or actual danger.

Given all that, it’s hard to see the past two decades of war against men such as Zawahiri as a strategic success.

The most egregious strategic misstep, however, lies in Afghanistan itself. In justifying the withdrawal from Kabul last year, Biden unconvincingly asserted that a new, over-the-horizon model of counter-terrorism would prevent the re-emergence of al-Qa’ida in Afghanistan. The Pentagon established an over-the-horizon counter-terrorism centre in Qatar, close to the headquarters of US Central Command. Yet the outgoing head of that command, General Kenneth McKenzie, testified this year that, with the loss of a permanent presence in Afghanistan, intelligence visibility into the country was less than 1 per cent of what it had previously been.

McKenzie warned that Islamic State and al-Qa’ida were growing in Afghanistan, and that Islamic State would be able to use Afghanistan as a base for external attacks within the next 12 to 18 months. He acknowledged that the military had yet to launch a single strike within Afghanistan – something that remains the case today since Zawahiri was killed by the CIA, not the military.

Obviously enough, the strike that killed Zawahiri found him living openly with his family in downtown Kabul, in Sherpur district – a former diplomatic enclave just north of the former presidential palace – in a home owned by Mawli Hamza, chief of staff to Taliban foreign minister (and Pakistani protege) Sirajuddin Haqqani. Clearly the notion that al-Qa’ida would not re-establish itself in Afghanistan was fantasy.

More important, in eastern Afghanistan, in rural districts close to the Pakistan border, persistent reporting suggests al-Qa’ida bases and training camps are growing again as the organisation re-establishes itself in its old stomping ground. And this is to say nothing of Islamic State, enemy to both the Taliban and al-Qa’ida, whose leaders welcomed Zawahiri’s death even as they continue to exploit Taliban weakness to build their own Afghan safe haven. And they have their choice of billions of dollars of military equipment abandoned by the US during last year’s chaos.

All in all, while Zawahiri’s death was surely deserved – and may bring comfort to the families of 9/11 victims – the symbolism of this tactical success merely highlights the broader strategic impotence of “over-the-horizon” counter-terrorism.

We must do better lest the entire deadly cycle of the past two decades repeats itself.

David Kilcullen is The Australian’s contributing editor for military affairs. Kilcullen served in the Australian Army from 1985 to 2007, and subsequently worked for the Australian and US governments as an intelligence analyst and counterinsurgency adviser. His latest book, The Ledger: Accounting for Failure in Afghanistan, co-authored with Greg Mills, was released last year.

The killing of Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kabul last weekend was symbolically important but its operational impact will be minimal. If anything, despite its tactical precision, the strike emphasised the limitations of Washington’s preferred “over-the-horizon” counter-terrorism strategy.