Canberra should behave professionally and avoid extravagant language but our normal working, friendly, relationship with Taiwan, where we act in part to preserve Taiwan’s international space, is something we shouldn’t give up.

Beijing’s outlook could well be unusually frazzled and neurotic in the months ahead. Xi Jinping will be deeply disturbed by public demonstrations against his Covid-zero lockdowns. In China it’s extremely dangerous to protest publicly. The police respond ferociously. Xi’s decade of rule has aspired to total control over politics and society. That makes these demonstrations, their bluntness and their geographic spread, remarkable.

So here are three questions: what do the demonstrations mean? Is Xi’s rule under threat? How does this relate to Australia, and Barnaby’s splendid adventure in Taiwan?

The demonstrations reflect the complete unreasonableness of Beijing’s wildly excessive Covid-zero policy and its associated lockdowns. It’s important to get the sequence of Beijing’s Covid failure right. When Covid first hit, it was deadly. No vaccine existed. Populations were medically “naive”, open to the full ravages of the disease. It hit older people harder than younger people, but remember that good health systems in even wealthy Western nations and regions, such as northern Italy and New York, were overwhelmed. Literally millions of people died.

Remarkably quickly, Western science developed effective vaccines, especially the mRNA vaccines. Doctors and hospitals also learnt how to treat Covid more effectively. Antivirals came online. In the first stage, almost every jurisdiction in the world implemented lockdowns to some extent and these saved many lives. Once a population was vaccinated and armed with the better treatments, societies gradually opened up. Most people caught Covid but, especially if they were vaccinated, didn’t get too sick. This afforded societies extra protection, as vaccines mixed with mild infection gave hybrid immunity to the worst effects of the disease.

As Covid variants became more transmissible, Covid-zero became impractical. In any event, societies had decided to open up and reduce restrictions. This still meant a lot of people died from Covid, but far fewer than would have occurred before vaccination. Also, there were significant steps everyone could take to reduce their personal risk, especially vaccination. And it was just plainly impossible to stay locked down.

The lockdown phase suited China’s authoritarian police state very well. It could keep foreigners out and citizens locked up. While no one should believe official Chinese statistics showing a minuscule Covid death rate over the past two years, China certainly did experience far fewer deaths than India or the US.

But it produced weak vaccines of its own and because of its nationalist paranoia and pride it would not accept the more effective foreign vaccines. As well, the Chinese people deeply distrust their government at every level, even as they rely on it and often support its nationalism. So the vaccination rate was anaemic, especially for those most at risk, the elderly. Nor did the Chinese government push third and fourth vaccine doses.

Now, China must open up. The virus is too transmissible and the people are totally fed up with lockdown, which has had grave economic and social consequences. But because the population is not as vaccinated as it should be, or was vaccinated a long time ago, and because most of the population have not had a mild dose of Covid and recovered, this opening up will result in many needless Covid deaths in China. Good estimates range from 600,000 to two million. China does not have enough intensive care beds to cope; that is, to offer everyone who gets gravely ill appropriate care. That will be distressing for Chinese society and the government in Beijing.

The demonstrations show us that the Chinese people know all this pretty well. They indicate that despite the intense efforts the state makes to control information, more Chinese people have a better idea of what’s going on in the world than the Chinese state would like. They also show that, when push comes to shove, the Chinese people will oppose their own government. Nothing was more eloquent than protesters in many cities holding up blank sheets of paper to indicate that they are, as Chinese citizens, in effect allowed to say nothing at all to their government.

Nonetheless, these protests, magnificent in their way as they are, do not really resemble those of 1989 that led to the Tiananmen Square massacre. Unlike 1989, they probably don’t put Xi’s rule in any serious doubt. A dictatorship is most at risk when there is both popular unrest and division among the elite. Xi’s ruthless purges and promotion of loyalists mean there is much less prospect of elite division than there was in 1989.

Also, despite their political bravery, the agenda of these protesters is mostly about Covid lockdown, not political revolution. Kevin Yam argued compellingly on this page on Monday that Chinese people, like Westerners, want freedom and democracy. Nearly 25 years ago I wrote a book, Asian Values Western Dreams, which argued that every major Asian cultural tradition contained a concern for liberty. I wrote in that volume: “There is plenty within each Asian cultural and national tradition to support the democracy option.”

Nonetheless, every Asian society is more socially conservative than Western society in its present addlebrained incarnation, and certainly more supportive of authority. That is why an enlightened Chinese leadership would be able to liberalise a bit while holding the state together – as happened in the mildest way under the recently deceased Jiang Zemin and his successor Hu Jintao – more successfully than the Soviet Union managed under Mikhail Gorbachev.

Xi’s policies have reversed the timid liberalisation of the past in favour of full-throated Leninism. They have resulted in lower economic growth and poorer social outcomes for Chinese. But China remains an at least partly responsive dictatorship and is now in effect abandoning Covid-zero policies, even if it’s not saying so.

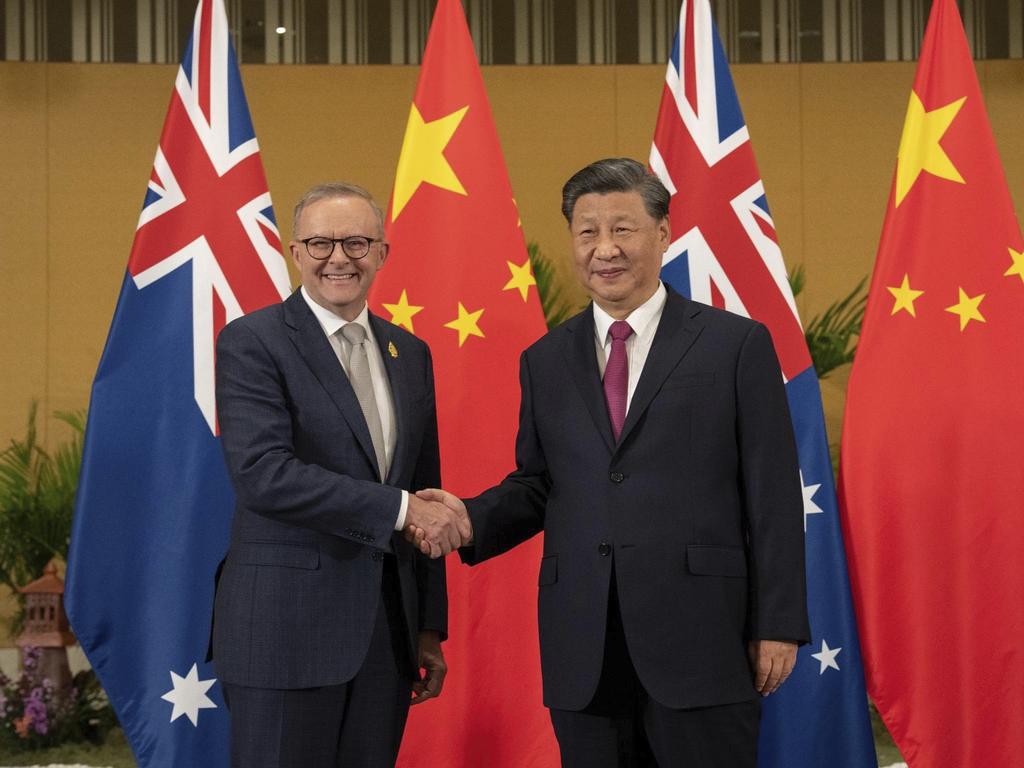

Xi hates being contradicted, most of all by his own people. Thus, even as Beijing has recognised just how counter-productive its season of wolf warrior diplomacy was for its own interests, and is trying to mollify its tone if not its substance internationally, we could now easily get a new swing back to paranoid hypersensitivity from the Chinese government, as evident in its criticism of the Joyce delegation.

If that happens, the Albanese government should continue what has worked so far – stay calm, speak moderately but clearly, and give nothing away. Including splendid and completely sensible parliamentary visits to Taiwan led by redoubtable ex-deputy prime ministers, with a touch of Sherwood Forest about them.

Barnaby Joyce and his merry band of men and women are absolutely right to be in Taiwan. If not exactly feared by the bad and loved by the good, they are certainly acting sensibly and with some political courage. In this period of “stabilisation” between Beijing and Canberra, we must not impose new limits on our normal behaviour to please the Chinese Communist Party.