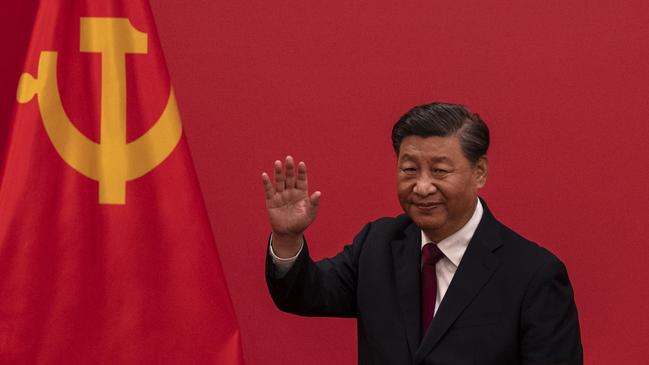

Consider what happened in global security in the days before the budget: Australia and Japan signed a security treaty that amounts to an alliance in all but name, including echoing the ANZUS treaty commitment to “consult” on regional emergencies. Xi Jinping emerged as China’s most powerful dictator since Mao, frogmarching his old rival Hu Jintao off the stage in front of the world’s media, while promising a militarised and more internationally assertive Beijing.

Joe Biden released a National Security Strategy that says China “is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it”. The view in Washington is that the 2020s will be the “decisive decade” for the “competition (that) is under way between the major powers to shape what comes next”.

Vladimir Putin is repeatedly claiming Russia will use tactical nuclear weapons in Ukraine while his forces have regularly risked damaging nuclear power reactors that could release radiation on the scale of a Chernobyl disaster or worse. This is the world we live in but none of that intrudes on the government’s assessment of the global economic outlook. The closest we get is an acknowledgment the Ukraine war gives rise to energy shortages and Xi’s manic Covid lockdowns threaten supply chains and will boost inflation.

To use a strategic planning term, this is absolutely nuts. Our government is failing in a basic duty to bring together an analysis of geostrategic and economic risk. This builds on deep wellsprings of Canberra bureaucratic ideology, in which Treasury dismisses strategic risk as unmeasurable and hence it is not factored into economic modelling.

Here is another example of the failure to draw strategic conclusions from economic assessments: the budget assumes China’s economic growth will be 3 per cent in 2022 and 4.5 per cent in 2023 and 2024. This may affect Australian commodity exports, but the bigger question will be what dramatically lower growth means for China’s domestic stability. It used to be claimed 6 per cent economic growth was the benchmark of Chinese Communist Party performance, below which domestic stability was at risk.

As his report to the just-concluded CCP Congress makes clear, Xi is battening down for a tough domestic ride, and hoping aggressive nationalism directed externally will distract from his party’s faltering performance. This could profoundly affect Australia’s strategic outlook.

For its part, Defence continues on its business-as-usual meandering. Not a dollar of Defence spending has changed as a result of this budget. We are still on track to build the world’s best networked and integrated Australian Defence Force, starting some time in the later 2030s.

To be fair, we now have announced for the first time a plan to build a National Security Precinct in Barton, near Parliament House in Canberra. According to budget paper No. 2, this is “following detailed business cases, planning and early market testing that commenced from early 2020”. This will provide a “permanent solution to the critical accommodation and capability requirements of several national security and other commonwealth agencies”.

It is being reported the national security precinct will house up to 5000 staff, which is about the number of troops the ADF could realistically deploy overseas in a military contingency. It is just as well the first building to be constructed is a multi-storey carpark.

The Albanese government is at some risk that it will have a national security precinct built in advance of a national security strategy. The budget this week was a lost opportunity – which come seldom enough in a three-year term – to start explaining how fundamental and urgent change is needed in Australian defence and security planning.

The government’s biggest defence planning opportunity will come in March 2023 when officials are due to report on a plan for acquiring nuclear-propelled submarines under the AUKUS agreement. Simultaneously, Stephen Smith and Angus Houston will hand over a final report with recommendations on the structure of the ADF. Policy decisions hardly get bigger or more consequential.

This budget offers no view on the potential cost of nuclear propulsion, but I will be astonished if it does not amount to something like a full per cent of GDP – that is, in advance of $20bn a year, taking into account recruitment, training, basing, weapons, operations and nuclear safety as well as construction costs.

The report by Smith and Houston will be even more important in the sense it needs to affect the immediate shape and investment priorities of the ADF. Big decisions are needed to give more hitting power to an under-gunned defence force. And something surely has to happen to shake Defence out of its grinding complacency. What is it that the department doesn’t get about our strategic outlook?

By way of a footnote, here is a budget measure that seems to have had little attention: under the heading First Nations Foreign Policy, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has been allocated $2m “to establish an Office of First Nations Engagement, headed by an Ambassador for First Nations Peoples”. So, does the voice now have a say on Australian foreign policy?

Will there be a First Nations defence and national security policy? Will there be carparks made available in the national security precinct? We wait to find out the things that really matter in Australian strategic planning.

The budget reinforces a depressing government blind spot: an inability to factor geopolitical risk into economic planning.