This is very well illustrated by the revisions to the safeguard mechanism negotiated by the government and the Greens and are set to take effect on July 1. Recall here that under the changes, the largest 215 emitters will be required to reduce emissions by 5 per cent every year until 2030, with penalties for noncompliance.

The theory is straightforward: if the aim is to reduce emissions, a cap-and-trade scheme like the SM is the most efficient mechanism to induce the least cost abatement.

Those emitters that can reduce emissions relatively cheaply can be awarded credits that can then be bought by those where it is technically difficult and/or expensive to reduce emissions. Credits/offsets from outside the scheme can also be permitted.

The trouble begins when the theory is translated into actual policy. It is only where there is a stand-alone cap-and-trade policy without the distorting paraphernalia of other subsidies designed to reduce emissions that the theory holds. Bring in these other measures, which have much higher abatement costs, and the gains of having a cap-and-trade scheme are lost. This has been the experience of the EU, New Zealand and parts of the US. Politicians almost always prefer the kitchen-sink approach to climate policy – throw everything at the problem and hope it works. At a minimum, voters will see a lot of action.

From an economic point of view, however, this is extremely inefficient and expensive. In Australia’s case, there is no intention of removing the vast array of climate measures of the federal, state or local governments. Even without this qualification, cap-and-trade schemes themselves are rarely pure and this applies particularly to the revised SM negotiated by the government. At the broadest level, one of its fundamental weaknesses is the discretion it gives to the minister to alter the rules as they apply to particular activities/projects and to reach individual bespoke decisions.

There are number of examples of this in the legislation. One is the potential availability of subsidies to exporting plants that are finding it difficult to compete with plants in countries without similar emissions restrictions – think here China and India, in particular.

There is also mention of moneys being directed to cement, steel and aluminium plants given the absence of any effective and affordable technology to abate emissions in these cases. The minister also has the discretion to ignore the overall cap in the event of that cap being exceeded because a particular project could go ahead.

These sorts of flexible provisions simply encourage rent-seeking by the participants as well as ensure relative silence on their part lest criticism of the scheme adversely affects their chances of securing special deals. This is the antithesis of good public policy and is reminiscent of the warnings given many years ago by US economist Mancur Olson that crony capitalism quickly leads to relative economic decline.

While the government has made much of the support of the Ai Group and the BCA, it’s not clear who these business lobbies are really representing. Certainly, in the case of the BCA, many of its members are professional services firms that stand to gain from the ticket-clipping that is an inherent feature of cap-and-trade schemes. There are also supporters of the scheme who think they will be able to pass the extra costs on to higher prices.

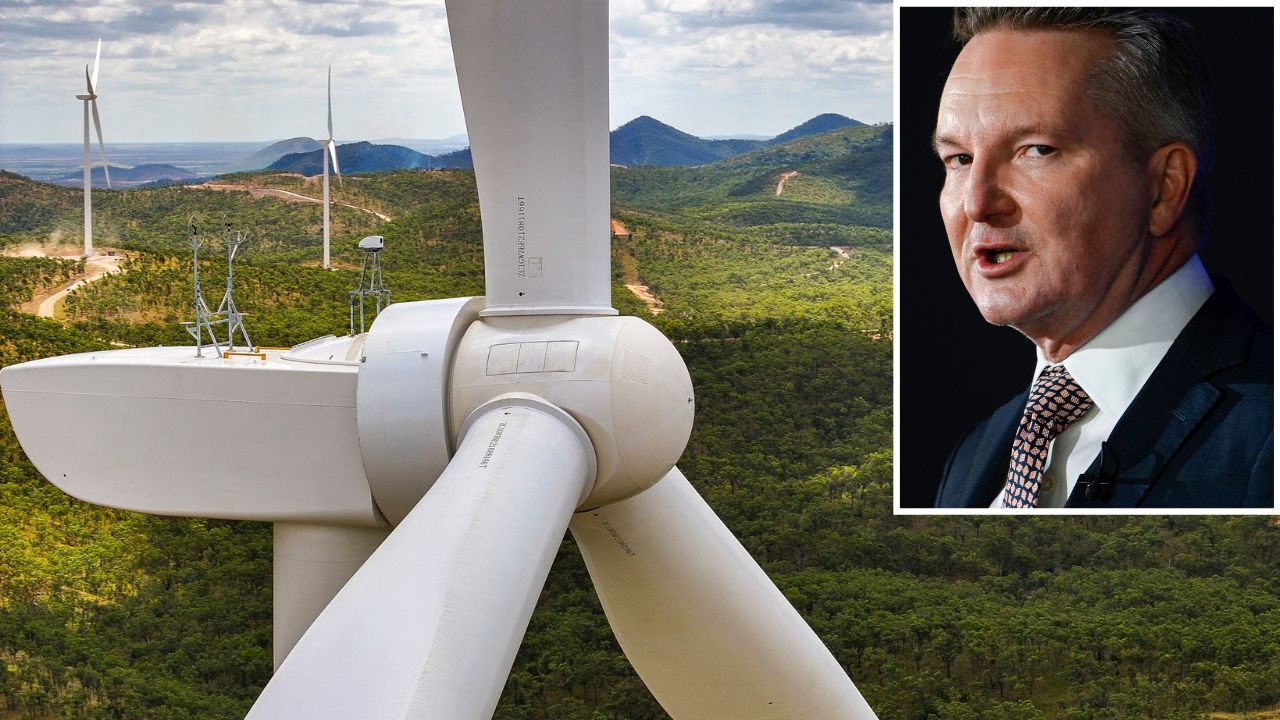

By contrast, there has been a steady flow of criticisms from the gas sector, where there are special sectoral rules – another very bad feature of the government’s legislation – to limit the use of offsets and to take into account Scope 3 emissions (those generated by the purchasers of the gas).

It is surely ironic the government has now seen the light on the centrality of gas to the transition of the electricity system while, at the same time, introducing measures that will make it much more difficult and costly for new gas projects to proceed. The application of a vaguely worded “pollution test”, agreed to with the Greens, for new gas and coal projects will surely deter the development of new projects.

There have also been concerns raised by the rail operators. A perverse outcome of the scheme may be the greater use of trucks and less use of trains because the scheme doesn’t apply to trucking. This is a classic example of an unintended consequence that economists warn about. Farming groups are worried that the additional demand for credits in the form of Australian Carbon Credit Units will eat into land that is currently used for the production of food and fibre. There is no doubt that the price of ACCUs will soar, which in turn will lead to higher prices.

Overseas-owned firms have a convention of refraining from commenting on local public policy issues.

Bear in mind here that a fair proportion of the 215 plants covered by the SM are fully or partly owned by overseas interests, including the big smelters. These firms will simply shift their investments to countries that are seen as generating the best returns for the lowest risk.

They will largely continue to operate their affected plants here in the short term, but may close them in due course. Let’s be clear here: reducing emissions by exits is the worst of all possible worlds. Emissions will simply emanate from other countries – new smelters in western China spring to mind, largely powered by China’s investment in new coal-fired electricity. In the meantime, Australia bears the economic loss including the retrenchment of high-paid unionised jobs in the regions.

It was telling that Glencore, one of the world’s largest resources companies, was willing to go on the record as warning Australia that Canada now looks like a preferable destination for its investment funds. The combination of the SM and other government actions (the higher coal royalty rate in Queensland was mentioned) is seen as a significant deterrent to further investment in Australia by the company.

The safeguard mechanism is a clear case of wishful thinking based on theory rather than hard-nosed analysis and real world considerations. The government’s delight in having the legislation pass may be short-lived. The fact is most large emitters will not be able to reduce their emissions in a linear way – 5 per cent per year. In many instances, it will require whole new technologies – for example, green steel – which are currently unproven and uneconomic. The temptation will simply be to shut up shop and set up in another country with less restrictive rules.

Economics can be a useful input into devising good public policy. But a major problem with much economic advice is that what might be right in theory is often wrong in practice.