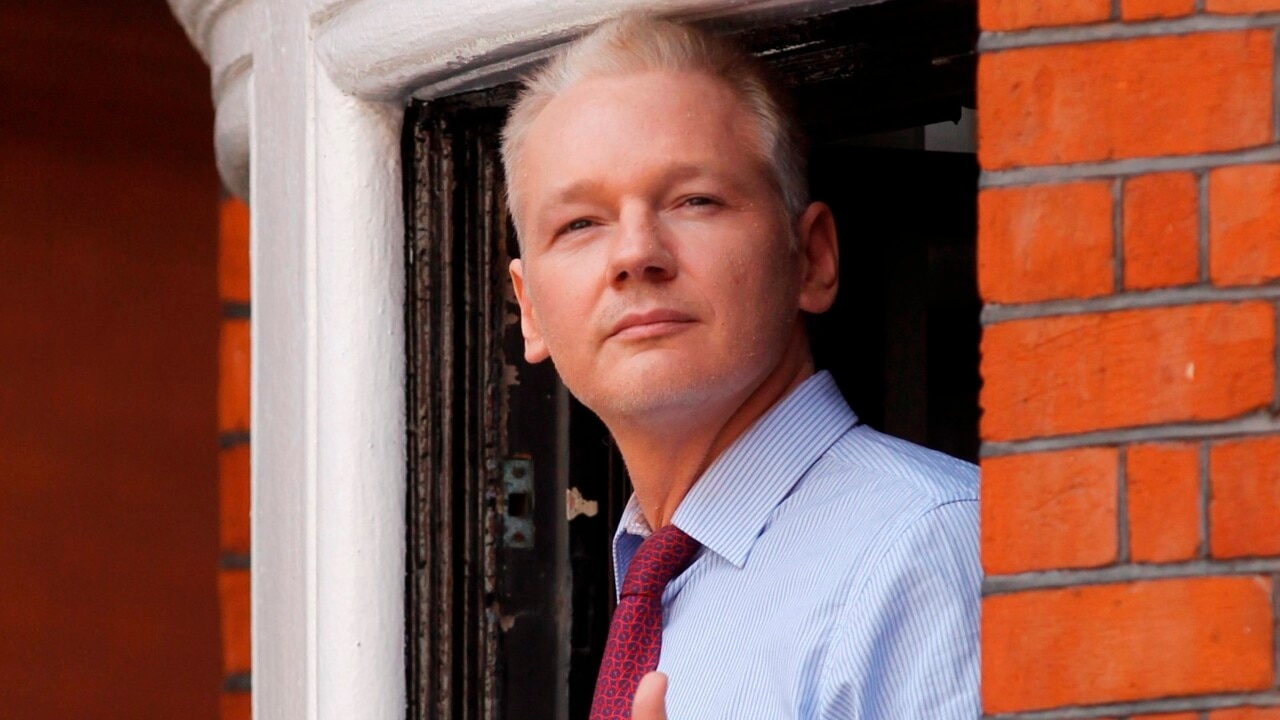

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange is a polarising figure, but this could help Anthony Albanese

The release of Julian Assange marks the beginning of the end to the legal dispute in one of the longest-running diplomatic and political sagas in Australia’s history.

But it is unlikely to bring an end to the contested public debate that he unleashed more than a decade ago.

Assange will remain a polarising figure, politically and within an establishment that has been divided over embracing him as one of their own – the media.

Assange’s liberty is unlikely to end this essential dispute; is he simply a criminal activist who endangered lives or a crusader of press freedom that his backers claim him to be?

Whatever one thinks of Assange and the crime he has finally confessed to, his incarceration, much of it self-imposed in London’s Ecuadorean embassy, had gone beyond farce.

Few would dispute that a legal resolution needed to be reached, whether that meant release or extradition to the US to face trial.

Anthony Albanese is being given credit for helping to bring about a conclusion favourable to Assange, on an issue that has been a thorn in the side of Australian politics for more than a decade.

It’s unlikely this outcome could have been reached had it not been for the political alignment on the left between Australia and the Biden administration.

This much is obvious, considering an angered response from former Republican vice-president Mike Pence after the plea deal was revealed.

The suggestion that this outcome has come about through a new bipartisan approach in Australia misreads the position of Peter Dutton – whose view remains that of every prime minister and opposition leader prior to Albanese sensing political opportunity before the last election.

And that has been that the Australian government had no skin in the game and it was a matter for the justice systems of the US and Britain. This position has been one held by both Labor and Coalition governments since the saga began.

It has been the only bipartisan position on Assange to have been maintained.

Few may recall Assange had threatened to sue former Labor prime minister Julia Gillard for suggesting he was a criminal 12 years ago.

It is Albanese who has been the change agent.

There are and may always be mixed views on Assange, what he did and what he represents. This goes beyond any sympathy derived over time since his arrest, bail-skipping, self-imposed exile and banishment to Britain’s notorious Belmarsh prison.

While he is most famous for the mass release of classified US cables and military logs from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars in 2010, few would recall Assange was also convicted in Australia in the mid-1990s for hacking, following charges to which he eventually pleaded guilty in order to avoid lengthy jail time here.

To some, he is a narcissistic villain; to others, he is the Libertarian anti-establishment poster-child for free speech and activist journalism.

The views on Assange haven’t been confined to polar positions on left and right. Ironically, support for Assange has come in its most vocal form from the extremes of the political fringes on both sides. The Greens and whistleblower MP Andrew Wilkie may have led the chorus on freedom for Assange, but the cause has expanded in recent years.

Former Queensland Nationals MP George Christensen, who once visited Assange in prison, had said: “There are a lot of Australians on the right and left who think that Julian Assange is a ratbag, that I am a ratbag, but that he should be brought home.”

Nationals MP Barnaby Joyce, on learning of Assange’s release on Tuesday, said: “It’s an issue that goes beyond Mr Assange; it’s about extraterritoriality. It’s about an issue about an Australian citizen who did not commit a crime in Australia, was not a US citizen, but had the prospect of going to the US for a long period of jail.”

Under Dutton, there has been doubtless a softening of the tone. While he has maintained continuously that the justice systems of Britain and the US had to be respected, he had questioned the delays in justice being served.

Dutton has also maintained a private dialogue with Albanese through the process of diplomacy with the US, signalling he too believed it was going on longer than was necessary or just.

While there was no unity ticket, Dutton could see no value in maintaining a hostile position on Assange, considering many Australians probably don’t remember how it all started in the first place and particularly when some of his own colleagues were starting to agitate.

He would be comfortable with the prospect of not having to talk about it anymore.

For Albanese, the obvious political dividend comes from neutralising another of the ongoing political battles between Labor and the Greens.