The 37-count indictment really has him bang to rights. In the clearest of legal prose, Jack Smith, the special counsel tasked with finding evidence against the former president, alleges an overwhelming case against him.

Trump took (in the final chaotic days of his presidency) and then conspired to hide the most sensitive classified documents the US government produces. He would show them to assorted unvetted and bemused guests of his Mar-a-Lago club. He inveigled his lawyer to destroy some of them when the FBI came knocking (the lawyer refused). He recurrently lied and obstructed the federal investigation into the documents’ whereabouts. Crucially, the special council alleges, he did all of this wilfully.

These are federal crimes. They are not the ugly but essentially trivial paying off of lovers. This time, conviction and jail time (in theory 370 years, or 10 years per indictment) loom.

Trump’s reputation as a betrayer of state secrets would be sealed. No foreign leader and their intelligence community would trust their battle plans in the hands of a second-term President Trump. Yet Trump’s popularity with his base remains undiminished. It has actually gone up since his indictment.

How are we to explain this? His obvious malfeasance, which has the real prospect of sending him to federal prison, seems to increase his support.

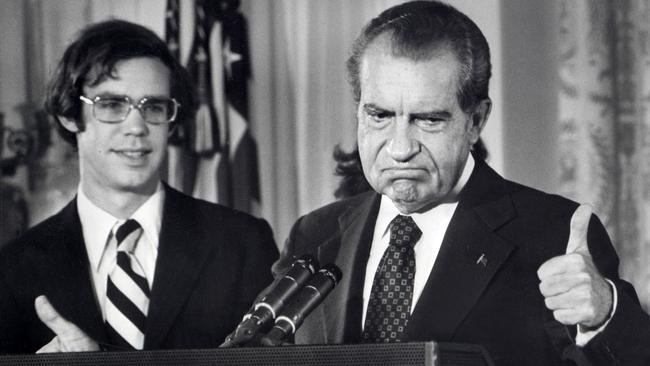

Why has Showergate not done for Trump among Republicans as Watergate did for Richard Nixon? Tricky Dicky knew the game was up when his own party deserted him. Trump, conversely, has his main GOP rivals lining up to indict the “deep state” that is coming after him.

Only former New Jersey governor Chris Christie has called this out. Why are senior Republicans so afraid of Trump, Christie asks, when “he hasn’t won a damn thing since 2016”.

To understand the fierce loyalty Trump commands, I lived for six months, last year, in the reddest state in the US: Wyoming. The ironically named Crook County is the most pro-Trump in America. The one county with a university (Albany), where pride flags are ubiquitous, even voted for him in 2016.

This week, all three members of the Wyoming congressional delegation derided the federal prosecution as political, “something that Third World countries do”.

Does Wyoming help us explain Trump’s hold on the conservative imagination? Yes and no.

While there is a respect for Trump’s bravado, the affection felt for him is less personal – not in those I met in the state – and more culturally strategic.

Like many Republicans elsewhere, Wyomingites love Trump less than they hate what he hates. He is a cause, a strategy that allows those on the right to push back against the sociocultural hegemony of the left.

The men and women they once relied on to do this, in the George W. Bush administration most notoriously, instead engineered China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation (destroying US manufacturing jobs), two disastrous Middle East wars (in Iraq and Afghanistan), and a global recession (which crashed the US housing market).

The right’s champions used to be officials such as Wyoming’s Dick Cheney. His daughter inherited the ire many Wyoming Republicans felt towards a Washington elite that had recurrently sold them out. She became a hate figure in the state not because she was anti-Trump. Rather, she was too pro-Washington, DC.

Liz Cheney became Trump’s nemesis last year, leading the January 6 inquiry against him – and losing the loyalty of Wyoming voters in the process. She lost her congressional seat to a Trump-backed challenger in November. In the 2000s, the right defended the father against the left; in the 2020s, the left defends the daughter against the right.

That new populist right is less partisan in a traditional sense but more anti-government. Trump has become its hero not for any carefully worked out electoral platform (he and his candidates keep losing after all) but because he is anti-government, too. The contempt with which he treats government documents is evidence of this and he is applauded for it. He hates what they hate.

His defence of coalmining – Wyoming produces 40 per cent of the coal America burns – only endears him to that state more.

The political left, of course, abhors populist heroes. But it has plenty of its own and grants them significant latitude. Bill Clinton could be fellated by an intern in the Oval Office and his party just looked the other way: “Everyone lies about sex.”

Ditto John F. Kennedy. His sex drive was legendary but Democrats, even after #MeToo, will not bracket him with Trump as a sexual harasser. (Trump has been accused of no sexual indiscretions in office.) Clinton and Kennedy continue to enjoy a Trump-style latitude among their supporters.

And there is the obvious double standard: Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton have each played fast and loose with federal files and emails. Yet it is Trump prosecuted for doing likewise. This is really the only political strategy open to him: “Why me and not them?!” It has considerable political resonance, even if it lacks legal realism.

A Trump in an arrowed prison uniform (in a cell with Nicola Sturgeon perhaps?) would make a mockery of American politics. But the more sinned against than sinning approach of Trump continues to inspire his base, in Wyoming and across the US.

Timothy J. Lynch is professor of American politics at the University of Melbourne. He was a Fulbright scholar at the University of Wyoming, 2022-23.

Donald Trump hoarding top-secret documents in his shower, among other places, is both utterly baffling and completely predictable. Baffling because there was no reason on God’s green earth that this could bring him anything but trouble. Predictable because only Trump’s ego, unique among men, needed the boost that wafting these files in front of B-list celebrities gave it.