The people had embraced a wave of liberal reforms that had granted freedoms of movement, press and creative expression – and the order had been made to subdue them.

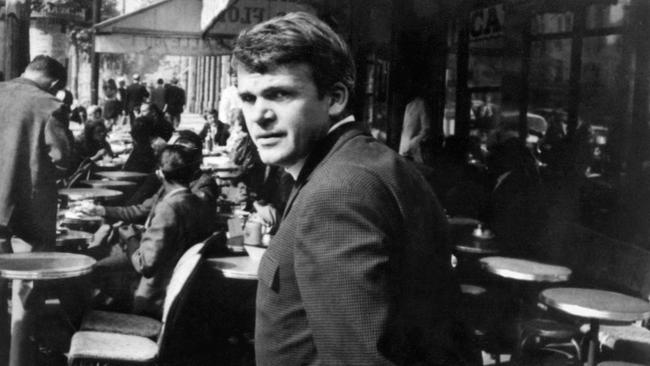

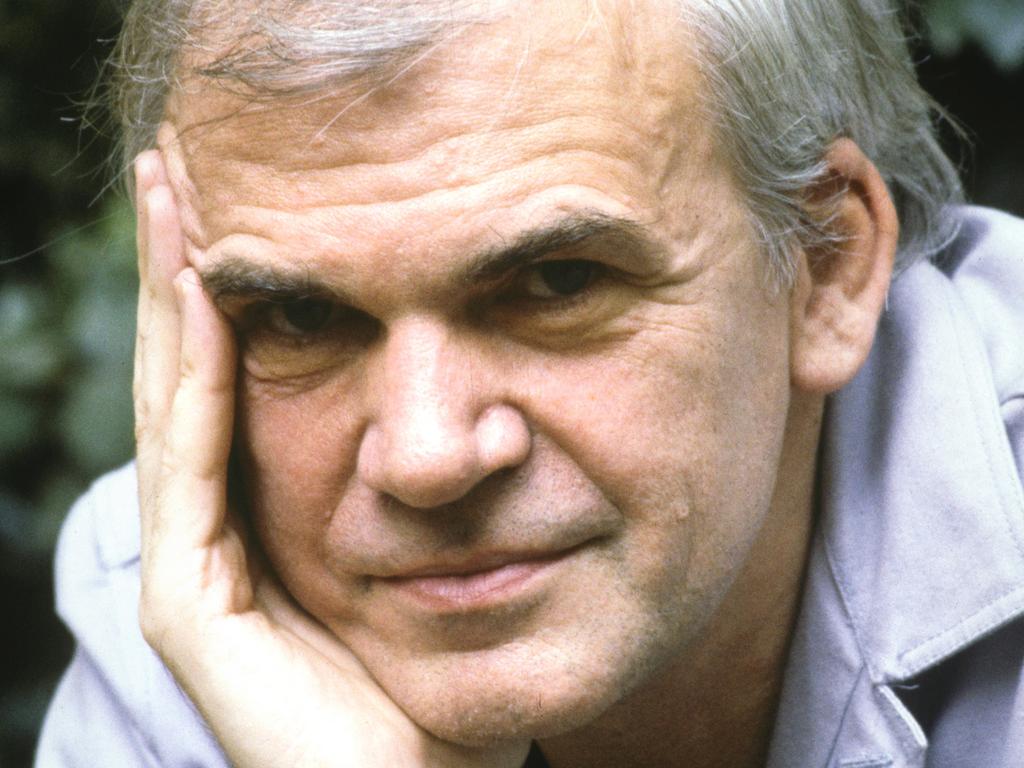

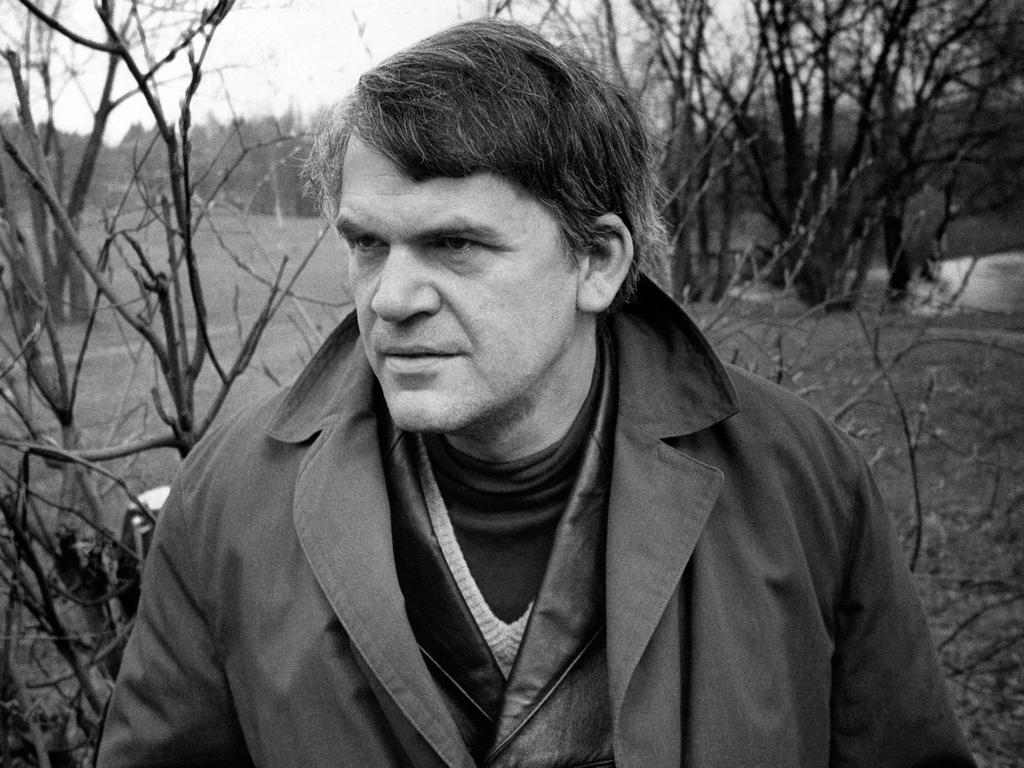

One of the creative voices emerging from this period was Milan Kundera, who died this week aged 94. A novelist who juxtaposed ephemeral joys with the experience of totalitarianism, he was considered one of the most original and penetrating writers of our age.

Born in 1929 in Brno to a middle-class family, he joined the Communist Party in his teenage years. Scarred from the horrors of the Second World War, his first poem was dedicated to a music teacher who had died in the Nazi death camps. His early work was staunchly pro-communist and he was “exalted” when the Communists took power in Czechoslovakia in 1948.

But as Kundera matured, so did his view of communism. Like many of his generation, he came to see the brutality enacted by his party was not just an accidental side-effect of revolutionary ructions, but a central plank of its guiding principles. By 1950, he was purged from the party for insufficient conformity, which became the major theme of his first novel, aptly titled The Joke.

Told through the eyes of a young student, Ludvik Jahn, Kundera recounts an atmosphere of suspicion and persecution that accompanied Communist Party study groups.

“Sometimes (more in sport than from real concern) I defended myself against the charge of individualism,” the protagonist narrates, “and demanded from others proof that I was an individualist. For want of concrete evidence they would say ‘It’s the way you behave’. ‘How do I behave?’ ‘You have a strange kind of smile.’ ‘And if I do? That’s how I express my joy.’ ‘No, you smile as though you were thinking to yourself.’ ”

The absurd nature of the vignette does not diminish its unsettling features. The young student goes on to recount how the suspicions of his fellow students made him question his own sense of self: “When the comrades classified my conduct and my smile as intellectual (another notorious pejorative of the times), I actually came to believe them because I couldn’t imagine (I wasn’t bold enough to imagine) that everyone else might be wrong, that the Revolution itself, the spirit of the times, might be wrong and I, an individual, might be right. I began to keep tabs on my smiles, and soon I felt a crack opening up between the person I had been and the person I should be (according to the spirit of the times).”

Kundera’s depiction of banal suffocation eerily parallels our own age. Afraid of speaking in class, lest they offend a peer, self-censorship among students today is the norm. Professors are reprimanded by university administrators for “liking” the wrong tweets. In many institutions academics are forced to genuflect to political causes to keep their jobs. While smiles may not be policed, comedy certainly is, with “problematic” jokes decidedly off-limits.

In The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, another of his earlier works, Kundera develops one of his major themes – that of historical amnesia. In describing how the Soviet-appointed president of Czechoslovakia, Gustav Husak, expelled 145 Czech historians from their positions in universities and research institutes, one of Kundera’s characters reflects: “You begin to liquidate a people … by taking away its memory. You destroy its books, its culture, its history. And then others write books for it, give another culture to it, invent another history for it. Then the people slowly begins to forget what it is and what it was. And the world at large forgets it still faster.”

While we do not live under the Iron Curtain in eastern Europe, and while we are not at risk of being subdued by armoured tanks, many Australians have displayed a remarkable desire to erase our own past in recent years. Electorate names are being changed to be more “sensitive”, and landmark names are being updated to become “appropriate”.

Across the country, local councils are currently voting to remove statues of early Australian premiers and prime ministers that remind us of our colonial past. Rather than contextualising this past – or creating new works of art – petty totalitarians simply obliterate.

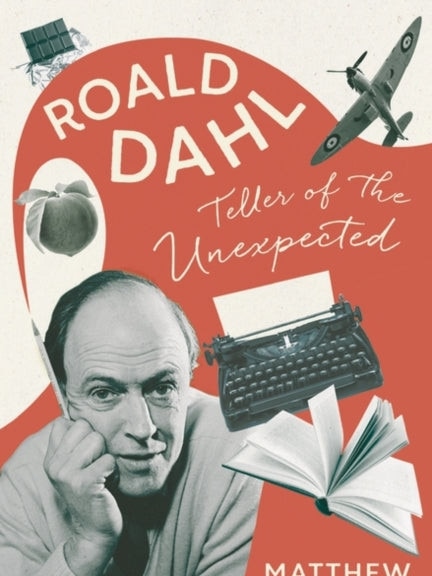

Other cultural artefacts being airbrushed include Roald Dahl’s books, which were recently edited to change words such as “fat” to “enormous” and “ugly and beastly” to just “beastly”. Other authors whose work is being edited to conform to contemporary sensitivities include Agatha Christie and Ian Fleming.

For decades Kundera resisted his books being digitalised, encouraging people to buy and read them in their paper form. Which makes sense if you remember digitalised texts are much more vulnerable to alteration by our cultural commissars.

In the end, although Kundera’s early works captured the feeling of being trapped in a rigid chamber of conformity, his later works, such as Immortality, eschewed political themes altogether. No less imaginative in style, they focused instead on the bigger questions of love and sex, life after death, meaning, and legacy. Like a true anti-totalitarian, his work focused on much more than just politics, and on questions far deeper than the grubby mechanics of power.

But, while Kundera’s oeuvre extended far beyond his early novels, his early work reminds us that the greatest rebellion against totalitarianism does not lie in self-aggrandising heroics, but in quiet acts of personal contemplation. While his novels are complex, multi-layered and intricate, a simple message shines through, which is that no matter how oppressive a political system is, the capacity of an individual to make his own choices – however small and however private – keeps him free.

Claire Lehmann is founding editor of online magazine Quillette.

At 11pm on August 20, 1968, a procession of T-55 tanks rolled into the streets of Prague. Made with thick armour and set with long-range rifles, Soviet troops were there to quell an uprising of the Czech citizenry, during a brief period known as the Prague Spring.