Why an Israeli ground fight with Hezbollah makes no sense

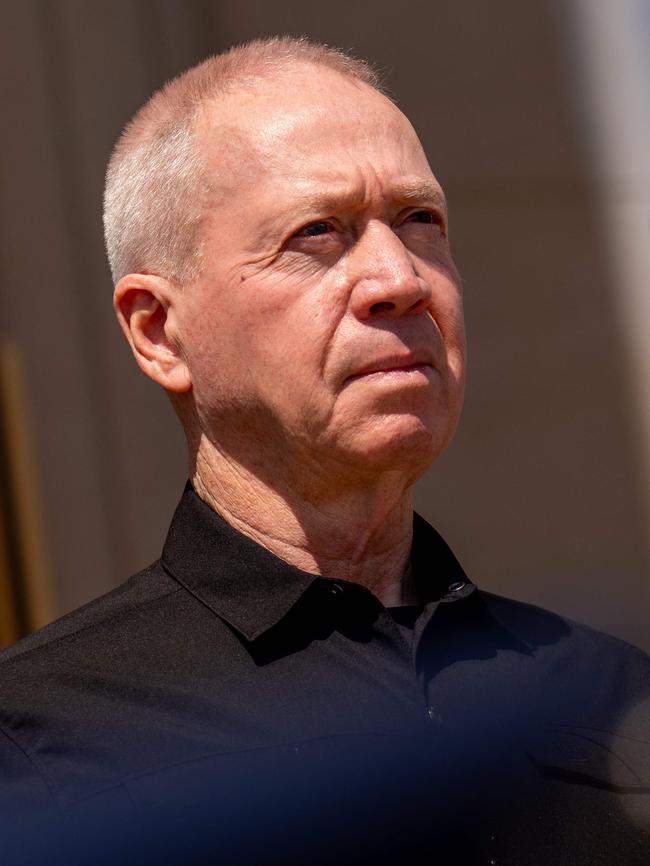

Israeli Defence Minister Yoav Gallant is one of the advocates, and threatened military action, while media reports suggest invasion plans for Lebanon have been agreed upon by the Israeli military. In Britain’s Telegraph, unattributed claims of Hezbollah weapons storage facilities at Beirut’s airport have also been reported.

At first blush it would appear counterintuitive that Israel – still engaged in a bloody ground campaign in Gaza – would contemplate a ground incursion against Hezbollah in Lebanon.

After all, Israel has a poor record of military adventurism in Lebanon. The south of the country is difficult terrain, providing an advantage to the defender – just as Australia’s own short but bloody campaign against the Vichy forces in that country during World War II illustrated.

A well-organised defence with disciplined troops can make life very difficult for an attacker.

Over the years, Israel’s occasional ground incursions into Lebanon have won them increasingly insignificant strategic benefits. In 1978, Israel’s ground incursion against Palestinian militants in response to an attack in northern Israel achieved tactical gains, but at a significant cost to the local Lebanese.

In 1982, a much larger ground operation was launched, initially to drive out the Palestinian factions from southern Lebanon. This resulted in the Israeli military advancing on Beirut to expel the Palestinians from all of Lebanon.

The Israelis didn’t extract themselves from Lebanon until almost two decades later, by which time the foreign Palestinian factions opposed to Israel had been replaced by a much more committed and capable local Lebanese Shi’a group – Hezbollah.

At the time, Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon was hailed not just as a victory for Hezbollah, but as a victory for all Arabs.

Six years later, Israel was back in southern Lebanon, following a cross-border raid against Israeli military forces by Hezbollah. The campaign achieved some tactical victories, but achieved little of any strategic consequence. The decision to go to war (and Israel’s ability to prosecute it) was heavily criticised by the Winograd Commission in 2006.

Ground campaigns are inherently complex and messy. Conducting them simultaneously on two fronts would stretch the capabilities of the best professional militaries in the world. Doing so with largely conscripted or reserve forces is even more fraught with difficulty.

Those who support Israel’s return into Lebanon will argue the Israeli military of 2024 is different to that of 2006, and that the lessons that arose from the hasty prosecution of the 2006 war had been well learnt.

Both these statements are undoubtedly true. But the 2024 version of Hezbollah is also more capable, with many of its members fighting in Syria to prop up the Assad regime. Moreover, Hezbollah has developed its technical capabilities – recent drone footage over Israel and a drone attack on the Israeli Sky Dew aerial observation platform were signals carrying a clear message: namely, despite Israel’s air superiority, its air supremacy can be challenged.

There is a political imperative to achieve a cessation of hostilities on Israel’s northern border so that tens of thousands of Israelis can return to their homes. But the way to achieve this is through a cessation of hostilities in Gaza.

Hezbollah has a domestic constituency to answer to, and its decision to stop engaging targets in Israel will be tied to an outcome in Gaza.

To think some form of ground action against Lebanese Hezbollah will stop rocket attacks against northern Israel is evidence of the same type of flawed logic which drove decision-making back in 2006. As much as they are an Iranian proxy, Hezbollah are still Lebanese and many of operatives live in the areas they operate in.

Unlike the Israeli troops who would enter Lebanon, Hezbollah would be defending their homes.

If the aim is to degrade Hezbollah’s rocket inventory and impose some form of buffer zone to buy time for the Israeli population to return to northern Israel, Hezbollah will continue to deploy longer-range weapons systems, or continue to harass northern Israel with shorter-range systems that will survive any ground offensive.

No ground incursion is ever as neat or as easy as it is envisioned. Having spent nine months battling to destroy Hamas in Gaza, trying to solve the Hezbollah problem by invading Lebanon makes little strategic sense.

Israel has learnt in the past that Southern Lebanon is not Gaza, and Hezbollah is not Hamas.

Rodger Shanahan is a Middle East analyst and former army officer.

More Coverage

Earlier this week in these pages, Jonathan Spyer suggested military action against Hezbollah was the best course of action to break the deadlock at the northern border.

Earlier this week in these pages, Jonathan Spyer suggested military action against Hezbollah was the best course of action to break the deadlock at the northern border.

An Israeli ground campaign in southern Lebanon would achieve no permanent improvement to security at the border and come at the cost of hundreds, if not thousands of lives.