When it comes to climate, China wins either way

They are only going to intensify as international tensions over the timeline for decarbonisation of the world economy threaten new geopolitical fault lines that will widen domestic divides.

Tensions with our allies over climate policy have not been put to rest. At COP26 in Glasgow this week, former US president Barack Obama lashed out at China and Russia for not doing “nearly enough” to address the climate crisis.

But the main international fault line is between energy-deficient developing countries that want more time and money to switch from fossil fuels, and governments of advanced economies committed to speeding up the transition to renewables.

Public opinion in developed countries and corporate money have swung behind the need to rapidly move away from fossil fuels. COP26 has reinforced this trend. More than 100 world leaders attended the Glasgow conference in person. Significant, though qualified, agreements have been signed to reverse deforestation, end coal production and reduce methane emissions underlined by the agreement between the US and China to ramp up co-operation on climate change.

But despite these achievements, only the most sanguine of optimists can now believe that temperature increases will be kept to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, the recognised benchmark for a generally benign climate.

Emissions will continue to rise in China, India and Russia. Many countries have failed to match their promises to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to the agreed level, making it far more likely temperatures will rise above 2C.

The world’s leading climate scientists are in little doubt about what this will mean for all of us.

A 2C-plus warmer world will not be a pleasant place to live. More frequent extreme weather events such as the destructive bushfires that ravaged Australia’s east coast early last year will place serious pressure on human habitation, freshwater availability and food supplies. Logic suggests we should do everything possible to prevent this climate future.

But energy realities threaten to trump logic and emotion.

Although there has been demonstrable progress in moving the developed world to renewables, poorer countries are still heavily reliant on fossil fuels and will remain so for decades.

For them, the here and now challenges of economic growth, jobs and energy security are paramount. Eco-fundamentalists do their own cause a disservice by insisting on unrealistic time frames to accomplish the most complex and difficult economic transition in history.

Support for action on climate change in the developing world ranks well below the level of concern evinced in Australia, North America and Europe.

That’s why big emitters such as China and India have resisted pressure at COP26 to commit to ambitious 2030 emission reduction targets and net zero emissions by 2050. But China also sees geopolitical opportunity in the climate wars that are aggravating political divisions within and between the advanced economies.

It hasn’t gone unnoticed in Beijing that Quadrilateral Security Dialogue members India and Australia are more aligned with China than the US on climate policy. Reassuring images of allied unity during the recently signed AUKUS agreement contrast sharply with Australia’s refusal to sing from the same policy song sheet as the US and Britain by eliminating coal and signing up to methane reductions.

Despite producing 31 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gases, Beijing has deflected criticism of its weak environmental credentials, a task made easier by the ideological blindness of climate change activists. Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg rails against the real and imagined policy failings of the West but refuses to criticise China even though it burns half the world’s coal. Some of the more than $US500bn ($685bn) Beijing allocates to its defence and security apparatuses annually would be better spent on securing the health of our shared environment.

Instead, China’s spurious claim to developing country status buys time not afforded to Australia to wean itself off reliance on fossil fuels and dominate the market for renewables.

China already produces 70 per cent of solar panels, has seven of the top wind turbine manufacturers and is a major player in the booming electric vehicle market. Allowing the world’s biggest emitter and user of coal 10 years longer than developed countries to become carbon neutral reduces its energy costs while driving up those of competitors.

The technological advantage enjoyed by the West in the production of internal combustion engines is being swept away as they are replaced by EVs, levelling the playing field. Either way, China wins. Far from being the result of superior foresight and planning, China’s emerging technology pre-eminence is primarily due to the ability of state-supported enterprises to undercut the prices of Western firms and control whole ecosystems.

This reinforces China’s market dominance and creates new dependencies that can be exploited for economic and geopolitical gain, as Australia has found to its cost. Scott Morrison needs to make sure his EV strategy is not as China dependent as our trade in resources and education services.

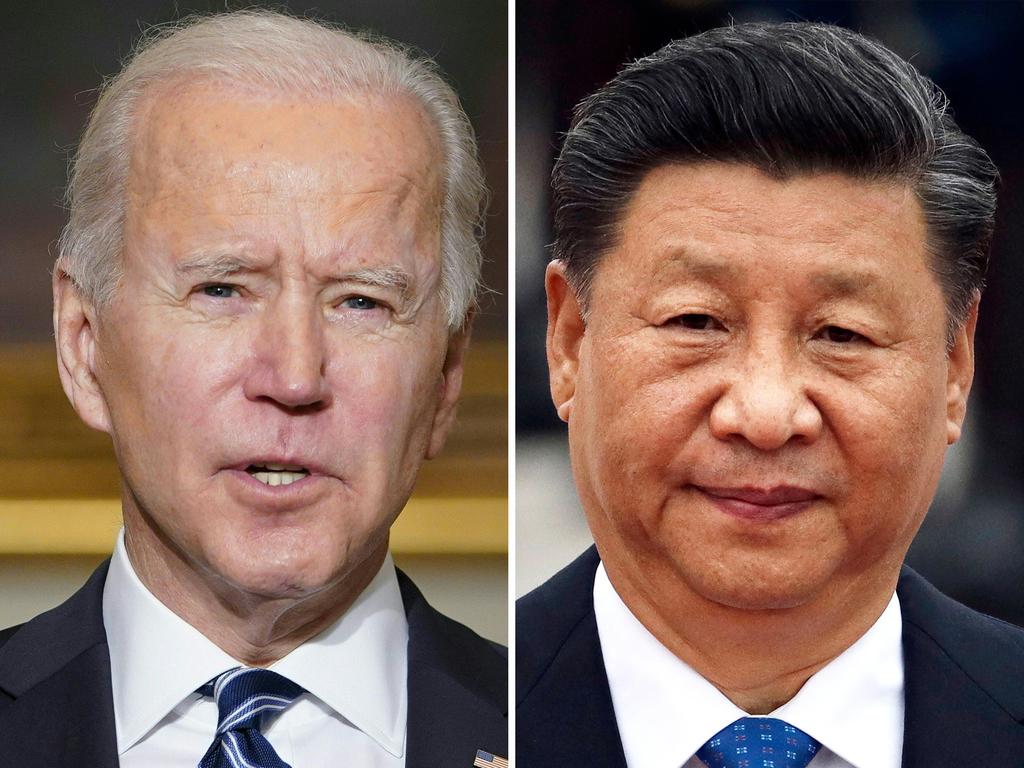

The Biden administration errs in believing co-operation with China on climate change can be separated from tendentious areas of the relationship. Beijing explicitly rejects compartmentalisation. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi made this clear in September, warning: “US-China climate change co-operation cannot be separated from the larger environment of US-China relations.”

President Xi Jinping is a devout practitioner of linkage diplomacy in which all elements of national power are harnessed in pursuit of specific foreign policy goals. Climate policy is no exception. Xi believes US pressure to make deep emission cuts is part of a strategy to limit China’s growth and contain its rise.

This means he’s unlikely to speed up decarbonisation of the economy or burn less coal; quite the opposite. Last year China built more than three times as much new coal power capacity as all other countries in the world combined and plans to add another 43 new coal-fired power plants.

The inconvenient truth is that unless China can be persuaded or pressured to reverse course, we are all going to be living in a much hotter world.

Alan Dupont is chief executive of geopolitical risk consultancy The Cognoscenti Group and a nonresident fellow at the Lowy Institute.

Don’t think that Australia’s climate wars are at an end.