Molan writes: “Australian society is as fragile as any other society in the world, and that this would surprise Australians is because our society has been spared for so long the effects of the worst kind of unnatural disaster – war.”

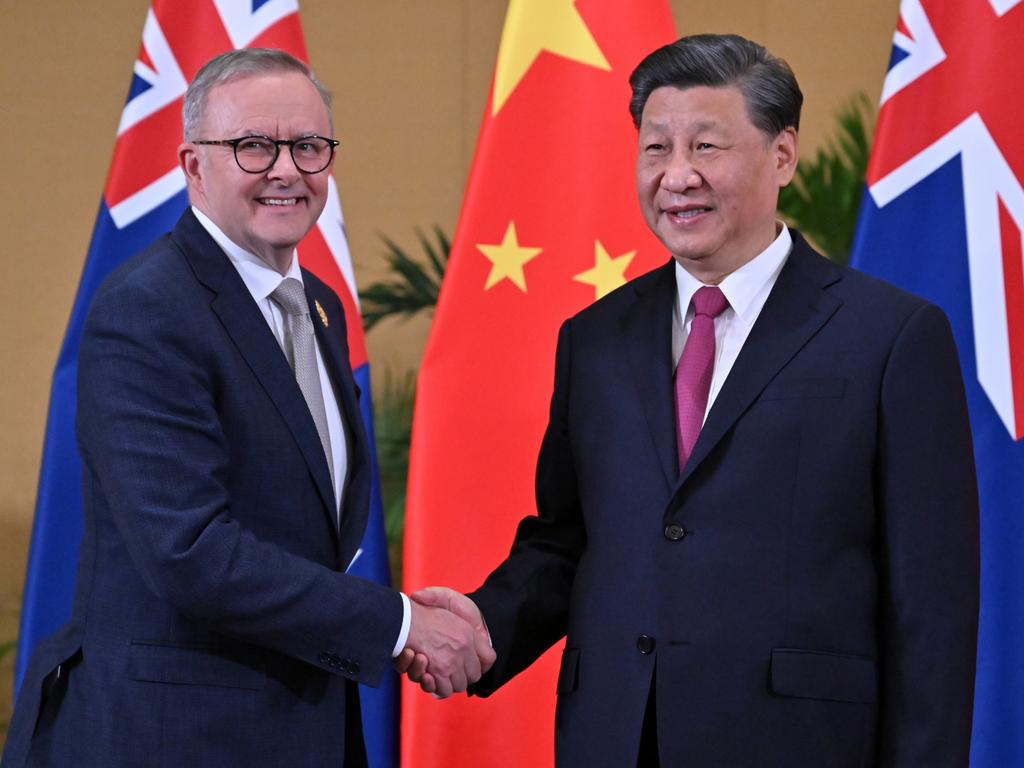

The Australian government is mired in uncertainty about what to do. “Without a tradition of strategy-making itself and with no preparation for such an event”, Canberra gives in to Beijing’s demands to abandon the American alliance, join the Belt and Road Initiative, supply ultra-cheap coal and iron ore to China. “That is what happens to tributary states.”

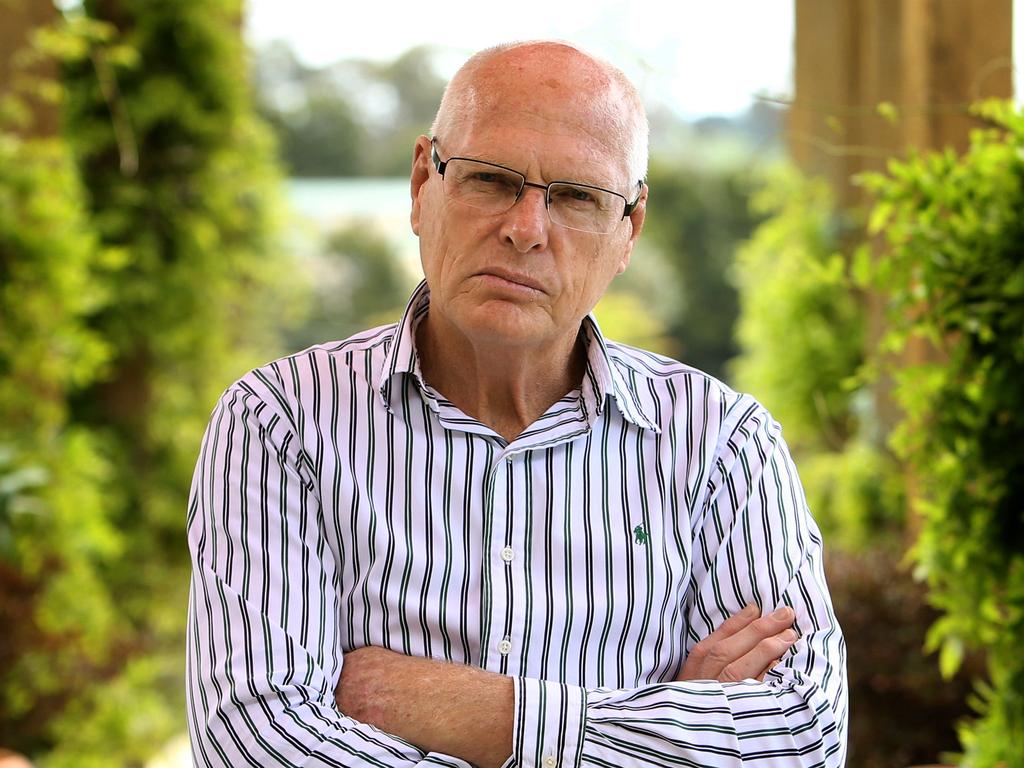

Molan wanted his book, released last August, to be a call to action, not a cry of despair. He worried in phone calls with me if, this time around, the government would pay attention.

You might think that Molan was a pessimist. Absolutely not. Jim most often had a broad smile on his face and was eager to discuss his latest idea and the next big thing that he, the army, the ADF, the government and the parliament should do. In the best way possible Jim was committed to a life of doing good things designed to strengthen Australia. He finished the book fighting his own terrible health battles but Jim didn’t complain. He was driven to share his enthusiasm for life and the adventures it contains.

I first met Jim (if my memory is correct) in April of 1998. He was a brigadier and defence attache in Jakarta. Ian McLachlan was minister for defence and I was his chief of staff. Then, an ageing president Suharto faced rising opposition to his authoritarian rule. Violence was intensifying in East Timor.

The challenge for John Howard was to keep a vital bilateral relationship peaceful while Indonesia faced strong global criticism for its cruel behaviour in Timor.

Defence links stabilised a relationship that threatened to unbalance. On his second posting to Jakarta, Molan spoke Bahasa and knew the TNI (Indonesian military) top leadership well. Jim and the embassy had succeeded in getting Indonesian agreement for the ADF to deliver disaster relief assistance into West Papua, an area off limits to official Australia. The aid saved thousands of lives facing a disastrous drought.

In Jakarta, McLachlan was hosted at a dinner by the head of the Indonesian military, General Wiranto, a presidential aspirant and an enthusiastic karaoke singer who had released a number of disks. Wiranto crooned Sinatra’s My Way – ironic given the Timor situation. A worried McLachlan knew his time at the mic was coming. He asked me if he should recite The Man from Snowy River.

“Don’t worry, minister,” Molan said before taking the stage and singing with gusto Halo, Halo Bandung, an Indonesian sentimental favourite celebrating the 1940s fight for independence from colonial occupation.

Imagine dozens of clapping and smiling Indonesian military officers and a handful of relieved Australians. We all loved Jim. His natural warmth was priceless in the dark days of August and September 1999 when rampant violence in East Timor threatened UN officials, Australians and Timorese alike. As a diplomat Molan was in Dili as much as Jakarta, negotiating with TNI and the militia leadership. He put himself under direct risk by evacuating people to the airport, getting them on to Air Force transport aircraft under the guns of agitated militia and soldiers.

Jim’s central role prior to Australia’s stabilisation operation is detailed in the just-released first volume of the official history of peacekeeping in East Timor by Craig Stockings. This is a brilliant history of a pivotal moment in Australia-Indonesia relations and of Timor Leste’s birth. The truth is powerful. Canberra officials tried hard to thwart its publication (a story for another day).

Molan says his role and that of his embassy colleagues was modest. Personal relations built over years limited the risk of a conflict between the ADF and the TNI. Strategically, though, he judges “the only things you can influence (directly) are inconsequential”.

Molan may be remembered more widely for the role he played as the most senior ADF officer deployed to Iraq in 2004-05 as the military coalition’s chief of operations. His 2013 book, Running the War in Iraq, is a clear account of the chaos that ensued from an attack against Saddam Hussein that did not plan for an occupation.

Molan helped deliver an Australian war objective – to lift the value of our alliance with the US through practical military professionalism. To trace the lineage of AUKUS, the latest expression of how we gain strategic leverage in Washington DC, look back to Australia’s role in Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Jim was searing in his private views and only slightly more muted in public comment about Australia’s under-gunned military. It isn’t possible to defend the country in our contested region with defence spending well short of 2 per cent of gross domestic product. Molan knew that and wasn’t afraid to say so.

Following Iraq, Jim made the case in Defence to build a joint force strong enough to make a difference in large-scale combat. His ideas didn’t fit the comfortable national consensus. This was in the day China was considered a happy money-making opportunity rather than a looming threat.

After he left the army, Jim played a key role in designing the Coalition’s Operation Sovereign Borders policy. He maintained that Australia did have the means to prevent unauthorised boat arrivals, challenging yet another Canberra consensus at the time. Others designed the practical strategies but Molan gave the policy impetus and standing.

In his brief political career, Jim argued for a national security strategy. His first recommendation in Danger on our Doorstep was to develop a “brutally honest” strategy that addresses weaknesses in “national resilience”, not just tinkering with ADF structure.

Inside the Morrison government, Jim didn’t find many listeners. “The idea of producing a written national security strategy is not popular with Coalition leaders, who prefer some government policy to remain much more informal,” he wrote. Why think things through when you can make stuff up?

Publishing Danger on our Doorstep was Jim’s way to bring the case for an honest national security strategy to a public audience. Australia’s national security thinking will be smaller and more blinkered without Molan at a time when we need imagination to prepare for the future – more ideas and less half-baked “issues management”. Read Danger on our Doorstep. Its Jim’s message about how we can defend the country and not succumb to despair.

Molan was a big ideas man operating in spaces – the Army, Defence, the Liberals, Parliament – that want ideas small and tightly wrapped. The mismatch spurred his enthusiasm for the contest of ideas.

In his book Danger on our Doorstep, Jim Molan describes a surprise attack from communist China on US and allied forces in the Indo-Pacific. Much of the US military in the Pacific is quickly destroyed, aircraft carriers sunk and bases in Hawaii, Guam and Japan rendered useless. Our Air Force is smashed by missile attacks at the start of the war. Much of our navy is quickly sunk and harbours are mined, halting trade. The army has no role beyond crowd control after looting begins for food, fuel and medical supplies.