If only he could. No one can say how the voice will be chosen, what powers it will have and exactly who can stand for it because all this would have to be decided after the referendum by the parliament; and then, most likely, further adjudicated by the High Court when a government’s decision-making displeases some or all of the voice’s members and arguably contravenes an expansively worded new chapter in our Constitution.

This referendum, should it pass, would be a blank cheque for change, and all that can be answered with certainty about a blank cheque is that it’s full of risk.

Pearson also says the voice is about Aboriginal people taking responsibility for their own lives. Again, if only. As the Prime Minister has said from the beginning, the voice will have no program-delivery responsibilities whatsoever and it won’t replace any of the myriad existing entities representing Aboriginal people or providing advice on their behalf. Because it would be entrenched in the Constitution, and because it would be an attempt to restore a measure of the sovereignty that Aboriginal people lost after 1788, it would take – in the PM’s own words – a very brave government to ignore it.

What the voice would have, in fact, is the opposite of Pearson’s claim – power without responsibility, the power to make endless demands without ever having to take responsibility for anything. Indeed, every failure and disappointment would be someone else’s fault; in the first instance the government’s for failing to spend enough to meet the voice’s demands, but ultimately the Australian people’s for the original sin of British settlement.

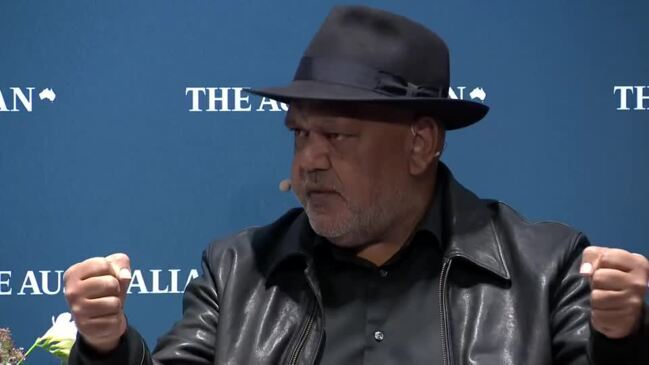

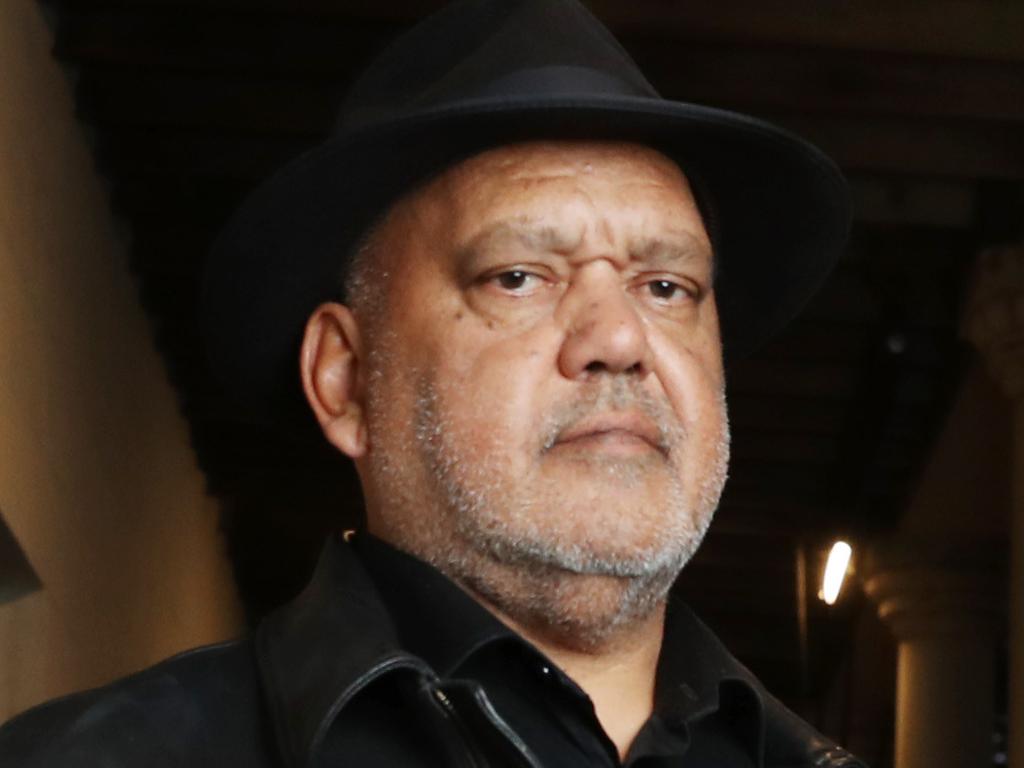

It’s good that Pearson now admits that the way the Yes case has been prosecuted is wrong. He now wants to engage with the opponents and the sceptics, instead of abusing them as closet racists or worse. Unfortunately for him, he can’t take back his disgraceful bullying of senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price for supposedly “punching down on black fellas” and allegedly being “caught up in a redneck celebrity vortex”. And he can’t retrospectively rewrite the Uluru statement for which he was one of the moving spirits.

The Prime Minister may not have bothered to read it, but the full Uluru Statement is a lengthy tirade against Australia, as the activists’ mantra – Voice, Treaty, Truth – reveals. Its Our Story segment is a denunciation of Australia’s history as a story of shame, characterised by official violence, even genocide, and ongoing oppression.

Even though this generation of Aboriginal people are not victims and this generation of non-Aboriginal Australians are not oppressors, the voice would mean that all of us and our descendants would have to live forever with institutional arrangements enshrining compensation for the crimes of some Australians’ ancestors against other Australians’ ancestors.

That today’s Indigenous disadvantage is the result of intergenerational trauma arising from British colonialism is a neo-Marxist fiction, yet it permeates the full Uluru statement. Even the one-page cover version refers to the goal of a Makarrata commission. Far from being a peaceful coming together, makarrata is a Yolngu word for a retribution ritual, a disabling spearing in the thigh to atone for a wrong. In this sense, what the statement’s authors want is payback for the past 240 years of nation-building as if there have been no compensating benefits for the original inhabitants.

In times past, Pearson’s public advocacy has been of great service to our country. In denouncing welfare dependency as the “poison that’s killing our people”, he was telling a profound truth transcending race. In demanding back-to-basics education, including rote learning of facts, he hit on the roots of so many modern Australian problems. In calling for a kind of “cultural interoperability” where Aboriginal people were immersed in their own high culture, as well as the best that has been thought and said, Pearson was expressing an ideal to which we all should aspire.

In articulating the concept of orbits that might begin in remote Australia but then lead anywhere in the world, he was trying to liberate Aboriginal people from being tied to a particular patch of land without losing a spiritual affinity for it. He was also right to point to the three pillars on which modern Australia has been based: an Indigenous heritage, a British foundation and an immigrant character. If only he’d been ready to enshrine this in the Constitution as a gracious acknowledgment of everyone and everything that has made us, rather than try to retrofit an ancestry-based fourth arm of government into our nation’s foundational document.

If only the Mandela side to his character hadn’t been subsumed these past few years by that of a tribal chief waging a guerrilla campaign against an oppression that is long since past and that has been replaced by the “tyranny of low expectations” that a grievance and entitlement-obsessed voice would just reinforce.

From 1788, the land mass that became known as Australia has been on a decisively different and better path. It’s no disrespect to the First Australians, or their achievements in surviving so long in what was then a very challenging environment, to say that they too have been the beneficiaries of British settlement. “The world’s oldest continuing culture” now has the advantage of equality before the law, respect for women and other minorities, and previously unimaginable technical advance. For all the mistakes of the past, this should no longer be a matter of grievance or guilt to anyone.

Instead, whatever our ancestry (which is invariably mixed anyway) we should feel immense pride in Australia’s achievement in becoming the least racist and most colourblind country in earth. The last thing we should do is jeopardise this by intruding into our Constitution this latest manifestation of identity politics. Pearson still hasn’t apologised to Price, perhaps because her warm embrace of the Indigenous, the Australian and the more broadly Western elements in her character shows a magnanimity that Pearson has lost and is only now belatedly trying to regain.

Voting No to this divisive voice should mean a reset to the Indigenous separatism that has bedevilled us these past five decades and allow all Australians to go forward again as one united people.

Tony Abbott is a former prime minister of Australia.

In a calculated pitch to The Australian’s readership and in a sharp change of tactics, the main Yes campaigner, Noel Pearson, now says it’s important to answer people’s questions about the voice.