Australia’s nosedive in academic results has stalled, the first post-pandemic PISA test results reveal.

Even so, about half the teenagers in year 10 failed to meet the basic minimum standards in reading, mathematics and science.

This is the “long tail of disadvantage’’ that former Labor prime minister Julia Gillard pledged to fix when she introduced national testing of literacy and numeracy, and poured billions of dollars into extra funding to help the disadvantaged.

Fifteen years later, the privilege gap has only grown wider.

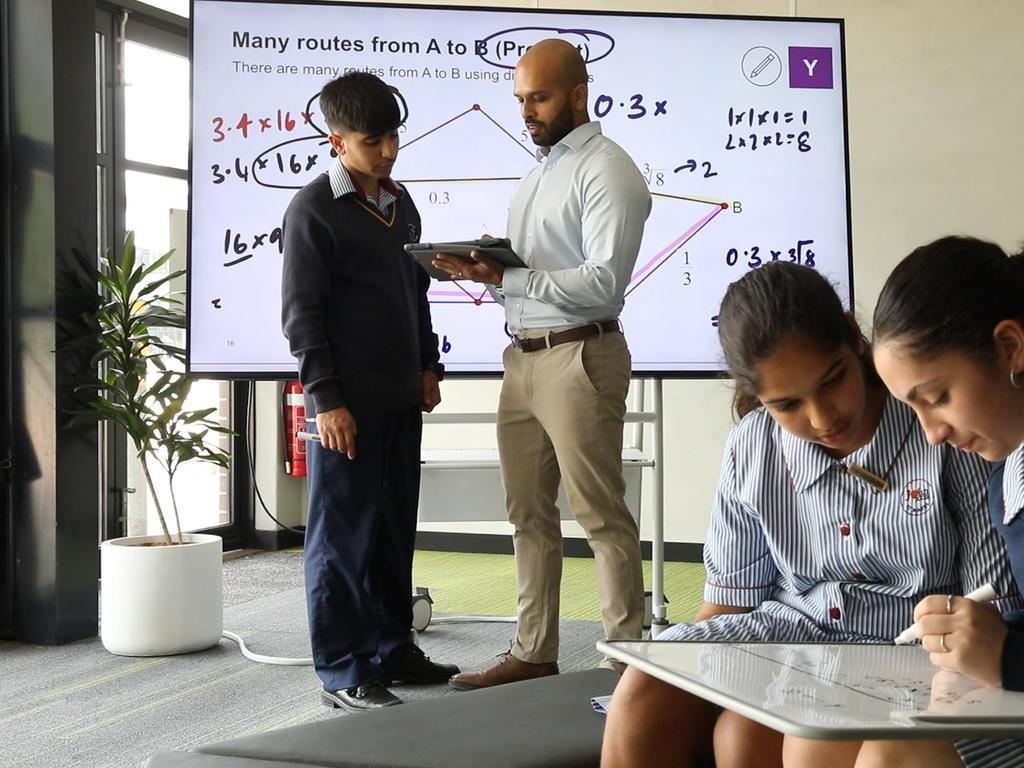

Students with parents who have enough money to pay for private school fees and expensive tutors are years ahead of their poorer classmates.

Wealthier parents are more likely to be well-educated, to read to their young children, and to promote school as important.

Kids who are sleeping in cars, or turning up to school with a rumbling tummy are unlikely to excel.

The fact that disadvantaged children are four years behind their well-heeled classmates gives them a lifelong educational handicap.

They’re more likely to drop out of school and fall into unemployment, perpetuating a cycle of poverty, poor health and crime.

Australia’s education ministers must stop schools in poor suburbs becoming educational ghettos, marred by low results and disruptive classrooms, as the better-off families transfer their children into private school havens.

The top teachers must be paid more money – a hardship payment – to teach and inspire children in the most disadvantaged schools.

Teachers must enforce the new ban on smartphones in classrooms and ensure their students are doing schoolwork – rather than watching YouTube or gaming – on their school laptops.

Big-tech companies must grow a conscience and stop cashing in on children’s obsession with games and social media that are designed to be addictive.

Seven years ago, the retiring headmaster of Sydney Grammar School, John Vallance, copped flak when he warned that spending on laptops in classrooms was a “scandalous waste of money’’ that would inhibit learning.

“I think when people come to write the history of this period in education,’’ he told me at the time, “this investment in classroom technology is going to be seen as a huge fraud.’’

How prophetic.

More Coverage

Money buys marks in Australia’s schooling system, where First Nations children, poor kids and those living in the bush have fallen years behind their wealthy, white, city classmates.