It was the 1960s, and Reynolds had come back from Britain to the Townsville University College, now James Cook University.

The message from his elders, according to writer Dean Ashenden, was “Australian history was down market but Aboriginal history, like the Aborigines themselves, was beneath notice”.

As we know, and as Ashenden reminds us in his prize-winning book Telling Tennant’s Story: The Strange Career of the Great Australian Silence (Black Inc, 2022), Reynolds didn’t take much notice of his colleagues and in 1981 published a comprehensive history of frontier wars and violence.

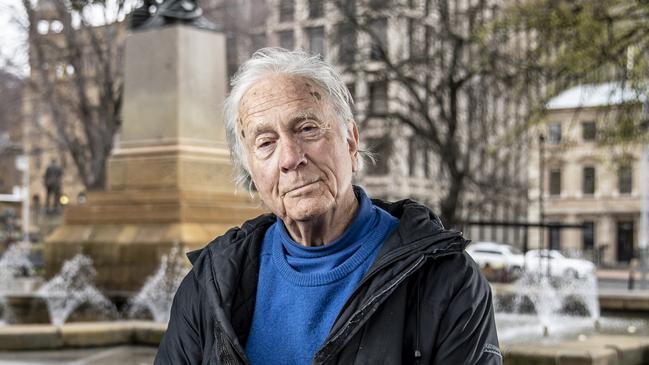

The Other Side of the Frontier: Aboriginal Resistance to the European Invasion of Australia is just one of many books by Reynolds, who also played an important part in the Mabo court case that overturned the fiction of terra nullius. At the age of 84, Reynolds can survey a country – and a profession – that is relentlessly uncovering the country’s history before, during and after 1788.

The silence of Ashenden’s subtitle is no longer as Australians engage in various ways with First Nations deep history and culture and begin to understand that “their” history is also “our history”. But it has been a long journey, one that Ashenden, an academic, political adviser and journalist, details in a book he has researched over many years.

Telling Tennant’s Story is Australia’s story in micro, but it’s also Ashenden’s story, and the story of so many of his generation who, thanks to a combination of collective denial, government policies and the relative lack of attention from universities, blithely managed decades of ignorance about First Nations people.

It’s not a guilt trip but it is a journey of acknowledgment.

Ashenden takes his cue from the famous line in WEH Stanner’s 1968 Boyer Lectures about “the other side of a story over which the great Australian silence reigns, the story, in short of the unacknowledged relations between two racial groups within a single field of life”. That silence came easily in Tennant Creek, the Northern Territory’s rough, tough droving and goldmining town where Ashenden’s father was head teacher at the local school in the 1950s, and where the whites lived in a kind of parallel universe to Aboriginal people.

Ashenden writes: “We’d hardly arrived in Tennant before we found out about the kids from the mission. We saw them every Saturday night at the open-air pictures … we’d all be settled (in deck chairs) under our blankets against the cold desert nights and waiting for God Save the Queen when the kids from the mission would file in between us and the screen, crossing to the far side to the benches reserved for them.”

Ashenden sees black people around the town, of course, but “these were encounters as in a tableau. So far as I can recall, I never spoke to any of these Aborigines, nor they to me … The Aborigines were nearly invisible yet somehow always there somewhere: sometimes referred to, even discussed, but never explained.”

It is not so different in Adelaide in the ’60s when the silence is still deafening: Ashenden recalls how his cohort did no Australian history, “let alone the history of relations between black and white”. But things were changing on campus, with events that “turned into an uproar that subsequently rose and fell but never really went away – a freedom ride, a tent embassy, speeches and tracts and posters beyond counting, strikes, investigations, legislation and litigation, movies, books and docos, then Mabo, a semi-official accusation of genocide, and the ferocious history wars. All that provided the means by which people of my generation and demographic learned what we hadn’t been told and unlearned some of what we had.”

Eventually Ashenden joins the dots, linking his curiosity about First Nations history with his Tennant Creek experience. Much, much later, he returns to the town in an effort to understand the “other side” of its history. His discoveries provide a thread through his book, but this is much more than a personal memoir. Chapter by chapter, Ashenden details the policies and attitudes and actions of Australians from “the first encounters of black and white, through the work of the early anthropologists, the historians and the courts in landmark cases about land rights and the Stolen Generations, to still-continuing controversy”.

It’s a readable account that takes us back to the 19th century, but reminds those of us who lived through it of the twists and turns of the 20th century, those years when it seemed white Australia took one step forward, then another step back in Indigenous affairs.

Ashenden appreciates the challenges we have faced in fully accepting “Aboriginal history”.

In his chapter covering Reynolds’s work, he notes the challenge for historians of “how to really listen to Aboriginal people, how to use ‘oral history’ and how to see what had been hidden by convenient blinkers (the fact of Aboriginal land management, for example) or by the loss or destruction of documents (Aboriginal deaths from white violence, for example).”

And how should we understand the full implications of “that part of the story for the whole story” – the one we had been told of our “great good fortune in having occupied an uninhabited continent without opposition”?

We might have known it wasn’t so, but as Ashenden says: “The work to be done was emotional as well as intellectual.”

It’s a line that resonates today as Australians decide how to vote in the forthcoming referendum on the voice to parliament.

There are strong intellectual arguments to be had on both the principles and the details of the voice, but there is also clearly “work to be done” on the emotional, the symbolic, even the spiritual and metaphysical side as we seek a better understanding of our past.

The referendum asks us to look forward but also to look back at where we have come from and what we have done and not done.

Ashenden offers just one example of how complicated our journey has been. The 1980s saw big changes, he writes, with “intense scholarly debate (in a) field that was booming as well as transforming itself … An Australian Bicentennial Authority formed in anticipation of 1988 was a creature of those heady days.” The ABA determined on a “warts and all” approach, deciding to fund a special Aboriginal program, declining to support a re-enactment of the First Fleet, supporting historians “in their efforts to uncover uncomfortable truths”.

Big stuff, right? And almost forgotten now. Ashenden reminds us that in 1984, Hugh Morgan, the immediate past president of the Australian Mining Industry Council, delivered a stinging speech against the Hawke government’s plans on “land rights legislation, sacred sites, national parks and a treaty with the Aboriginal people”.

Hawke backed down and soon both the director and the chair of the bicentennial authority had gone. On January 26, 1988, the tall ships sailed through the heads of Sydney Harbour.

For some it was a failure, for others a victory – but, just like frontier wars and the tent embassy and Mabo and Wik, it is part of a history we need to confront, not bury.

When Henry Reynolds, the historian whose work has been fundamental to changing our knowledge of early white contact with Indigenous people, first became interested in Aborigines, he was told by academic colleagues “that was no way to get on”.