Consultation has, after all, always been a two-edged sword. It can certainly help governments obtain valuable guidance. But we usually take it for granted that those providing information also have interests to advance, so consultation can readily degenerate into rent-seeking.

The greater the extent to which interested parties will capture the benefits of policies without having to shoulder their costs, the stronger the incentives for rent-seeking must be; and the harder it is for governments to ignore their advice, the more likely rent-seekers’ interests are to trump the public’s.

Nor are those risks purely hypothetical. Consider, for example, Megan Davis’ strident criticisms of the Coalition governments for allocating contracts to deliver services in remote areas through competitive tenders, instead of privileging Indigenous organisations. It may be that the tenders were poorly managed; that calls, however, for tendering processes to be improved, rather than for scrapping competitive neutrality and the pursuit of value for money.

Yet it is obvious the burgeoning Indigenous professional and managerial class, which is likely to dominate the voice, has much to gain from contracts being awarded on race, instead of merit. And with Davis herself saying the voice should exercise a dominating influence on decision-making, the pressures for preferential treatment to be extended, advantaging Indigenous elites at the expense of their notional constituents and of taxpayers alike, could prove overwhelming.

None of that would have surprised the great thinkers who shaped our understanding of liberal democracy, such as David Hume and Adam Smith. Although wary of monopolies and cartels, they regarded trade and commerce, which is based on openly selfish calculation, as plainly desirable; but they also emphasised the need to curb private interests when they invade the public sphere.

“Political writers have established it as a maxim,” wrote Hume, “that in contriving any system of government, every man ought to be supposed a knave, and to have no other end, in all his actions, than private interest.”

The solution, Hume argued, did not lie in a pointless quest to populate politics with angels; it lay in designing institutions that tempered the risks, including by ensuring no voice was favoured over others on the battlefield of public affairs.

The immediate issue was the right to an equal say in public consultation, notably in petitioning parliament. Clause 5 of the 1689 Bill of Rights declared “That it is the right of the subjects to petition the king, and all commitments and prosecutions for such petitioning are illegal”; but restrictions on “humble petitioning” imposed in 1661 had not been entirely repealed.

It took the crusades against sectional interests waged by the antislavery league, the campaign to repeal the taxes on corn and the Chartists before the “equality of voice” that arises from the right of all British men and women to petition parliament was unquestionably recognised in 1853.

The need to curb sectional interests arose even more acutely in the context of parliamentary representation. In 1867, the Colonial Office had approved reserving four parliamentary seats for Maori in New Zealand as a reward to the tribal chiefs who had sided with the Crown in the blood-soaked Maori wars; however, British opinion staunchly opposed the formal representation of sectional interests in the House of Commons.

Thus, in his influential Essays on Reform, Albert Venn Dicey, the Victorian era’s pre-eminent constitutionalist, argued that instead of deliberating upon the public good, any group’s “special representatives” would believe that there was “something sacred in defending at all costs their own interests”: the result would be “incalculable evils”, as “the most fanatical, the most narrow” minds, ardent only in the pursuit of their own advantage, turned politics into an exercise in grabbing other people’s income.

That tussle was not an exercise in “dividing a pie”; more like a brawl in a porcelain shop, it destroyed whatever there was to share.

Those dangers have hardly disappeared; and it is beyond doubt that howls of protest would quite rightly have greeted a proposal to bestow on miners, bankers or farmers an exclusive, constitutionally entrenched right to make representations to parliament and executive government, with the privilege being denounced as a right to pillage the public till.

But if those howls of protest, which one would have expected the left to unleash, have been so muted in the case of the voice, it is because our zeitgeist is permeated by a particularly patronising version of the myth of the Noble Savage, in which innocence, victimhood and disinterestedness stand entirely on one side and culpability, cupidity and power entirely on the other.

Marc Lescarbot, the French lawyer and pioneering ethnographer who, after living among Canada’s Mi’kmaq Indians, somewhat ironically coined the term “the Noble Savage” in 1609, knew better. Precisely because he regarded the Indians as human beings, inherently no better or worse than others, he was convinced they “have no want of wit”, with their chiefs understanding every bit as well as their French counterparts how to be “subtle, thievish, and traitorous”.

Lescarbot is hardly alone in refusing to treat Indigenous peoples as mere victims; just listing the contemporary scholars who have shown the crucial role Indigenous “agency” has played in shaping outcomes would easily fill this column.

Historically, that role was constrained by a crippling power asymmetry; but those days are long gone. And just as it makes no sense to whitewash the past, so it would be absurd – and blatantly inconsistent with “truth-telling” – to deny that the Indigenous administrative and managerial class has been instrumental in the conception, delivery and, yes, repeated failure of the policies intended to “close the gap”.

To assume that once they are empowered by the voice, they will reverse, rather than enhance, the separatism that underpins those failures – and that has helped assure that class’ ascension – is a triumph of hope over reality, perpetuating yesterday’s delusions at the expense of tomorrow’s progress.

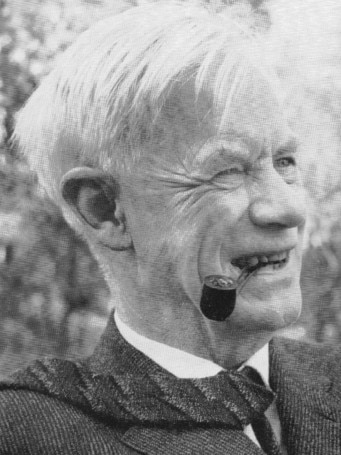

But Australians are a weird mob. As WK Hancock famously put it in Australia (1930), while “generally matter-of-fact people who distrust fine phrases and understand hard realities, in politics they have been incurable romantics”. “Fond of ideals and impatient of techniques, their sentiments quickly find phrases, and their phrases find prompt expression in policies” – policies that allow “swarms of petty interests” to harm those they purport to help.

Whether we are about to repeat that mistake is the great question of the moment.

If there is a ghost lurking behind the debate about the voice, it is that of the Noble Savage. That is not to trivialise the problems the voice is intended to address, nor to question the sincerity of many of its supporters. But the claims made on its behalf demand so stark a suspension of disbelief that they would, in any other context, be ridiculed as straining the credulity of the credulous.