The Prime Minister told Sky News recently we should vote yes because it “will make us feel better about who we are as a nation”. He misses the point. Most Australians feel good about the place already. What worries them is the voice will make a great country much worse.

Many Australians share Peter Dutton’s fear that the voice will “re-racialise our nation”, a statement dismissed by Linda Burney as “disinformation”. Yet Dutton’s assessment is correct, judging by an example of the representations the voice might make offered last month by Megan Davis in her Mabo Oration.

She argues that Indigenous Australians should be able to access their superannuation before other Australians because they live shorter lives. Early access to superannuation is already available to sufferers of chronic illnesses or those in other desperate circumstances. Determining one’s superannuation preservation age by race will grant privilege to anyone who identifies as Indigenous, regardless of wealth or the state of their health.

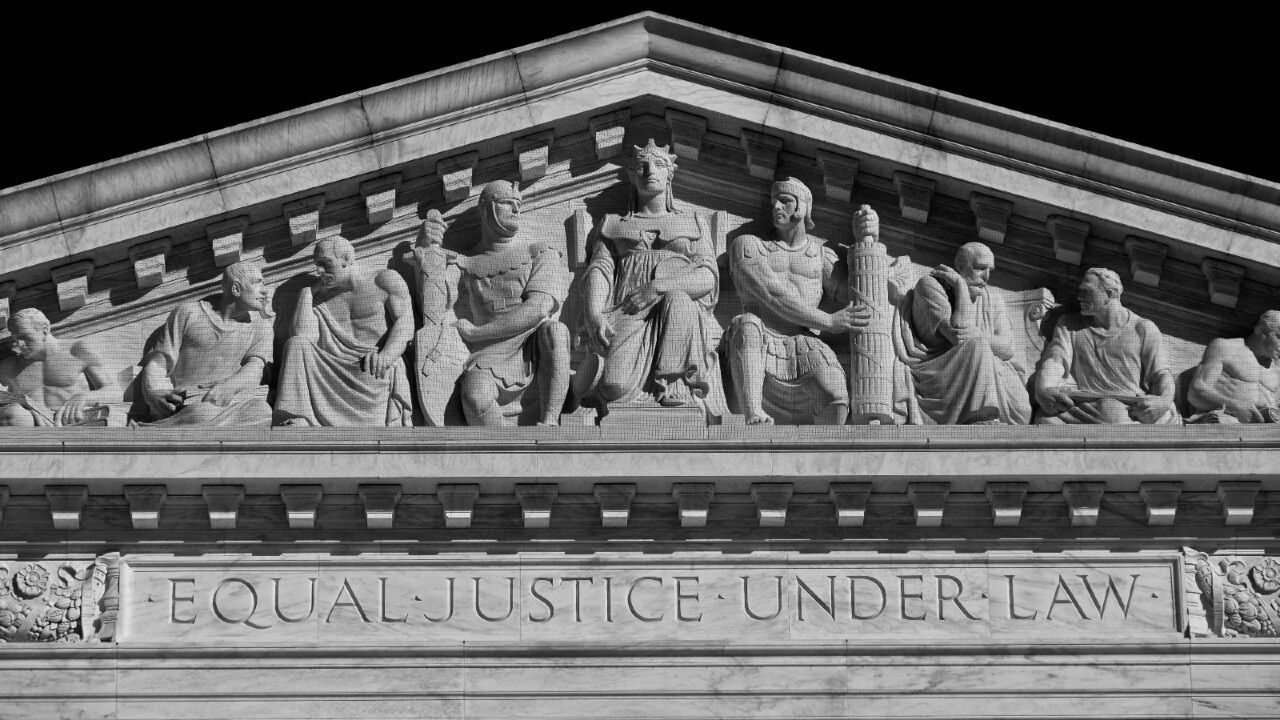

Measures such as these would be forbidden under the US constitution, which is bound to uphold the 14th Amendment passed in 1868 after the Civil War. Justice John Marshall Harlan eloquently expressed the amendment’s intention in his dissent to the Supreme Court’s 1896 decision in Plessy v Ferguson, which upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation.

“Our constitution is colourblind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens,” wrote Harlan. “The law regards man as man and takes no account of his surroundings or of his colour.”

Australia’s 14th Amendment moment, as far as we’ve had one, was expressed in two decisions taken in 1967 under then prime minister Harold Holt. The first was the end of the White Australia policy, which allowed immigration decisions to be determined by character but not by race. The second decision was the referendum in May 1967, passed by a majority of 90.4 per cent.

The 1967 referendum removed any grounds for official discrimination against a particular race. However, it allowed governments to discriminate positively in favour of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, leaving the door open for affirmative action.

The notion that it’s possible to discriminate in favour of one group without discriminating against another is firmly refuted by last month’s US Supreme Court ruling, which declared race-based admission programs for universities to be unconstitutional.

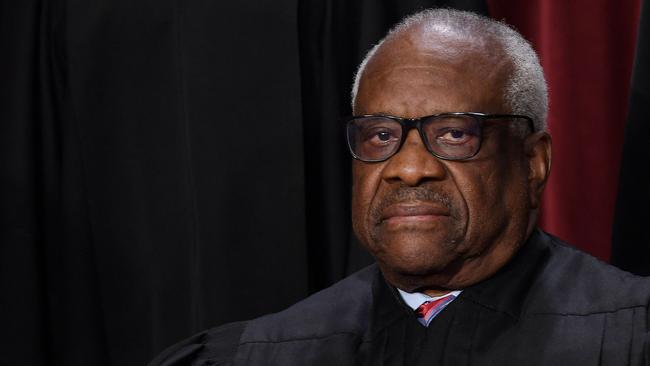

It considers the discrimination it creates for white and Asian students applying for a fixed number of college places, arguing that one act of racial discrimination cannot be corrected with another. Justice Clarence Thomas – an African-American born in 1948 in Pin Point Georgia in the then segregated South – is the most eloquent defender of the court’s decision. At the age of two, after his father abandoned the family, he was raised by his grandfather in a poor community near Savannah.

Thomas was admitted to Yale Law School via a Catholic college in Worcester, Massachusetts, but later claimed it was a mistake. When he applied for jobs at law firms, he said he was “asked pointed questions, unsubtly suggesting that they doubted I was as smart as my grades indicated”.

That may help explain Thomas’s passionate and originalist defence of the 14th Amendment and his argument that discrimination is always wrong, regardless of intention. “I have long believed that large racial preferences in college admissions stamp blacks and Hispanics with a badge of inferiority,” he writes.

The accomplishments of all members of the minority group are tainted since those who succeeded purely on merit are undistinguishable from those whose race played a role in their admission. “When blacks and, now, Hispanics take positions in the highest places of government, industry, or academia, it is an open question whether their skin colour played a part in their advancement,” he writes.

Thomas is among a shrinking minority of African-Americans who could reasonably claim to have been directly harmed by the segregationist policies in place for the first 16 years of his life. Yet he makes no claim for special treatment, warning that the dangers of pursuing historical grievances are unacceptably high. Today’s teenagers – who did not live through the Jim Crow era and did not enact or enforce segregation laws – “do not shoulder the moral debts of their ancestors”, Thomas writes “Our nation should not punish today’s youth for the sins of the past.”

Thomas’s chief antagonist is Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, a fellow African-American and one of three Supreme Court justices to dissent from the judgment. Jackson’s dissenting judgment says the majority decision “fails to acknowledge the well-documented intergenerational transmission of inequality that still plagues our citizenry”.

“With let-them-eat-cake obliviousness,” she writes, “the majority pulls the ripcord and announces ‘colourblindness for all’ by legal fiat. But deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life … The only way out of this morass – for all of us – is to stare at racial disparity unblinkingly and then do what evidence and experts tell us is required to level the playing field.”

Jackson did not experience segregation, having been born in 1970, six years after the passing of the Civil Rights Act. She was born in Washington, DC, to college-educated parents, raised in Miami, Florida, and educated at Harvard. Jackson has, however, suffered the stigma created by affirmative action of which Thomas complains.

The subtext to much of the questioning she experienced during her torrid confirmation hearing last year was that her top qualities in the President’s eyes were that she was female, relatively young and black.

Jackson’s judgment rests lightly on interpretation, legal precedents and constitutional principles, and heavily on the rhetoric of victimhood, intersectionality and race. It lacks the literary eloquence of Thomas, who grew up speaking Gullah, a Creole tongue, as his first language and chose to major in English literature “to conquer the language”.

The temptation to equate the history of US race relations with our own is, for the most part, best avoided. Australia did not experience slavery or Jim Crow. To the extent that Australians have resolved their differences, they have done so without a Civil War. They have not experienced the bitterness and racial violence that culminated in the 1964 Civil Rights Act or the divisiveness of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Yet the spirit of the 14th Amendment, and last week’s persuasive judgment in its favour, should help us marshal our thoughts as we consider the pros and cons of the voice, which is an explicit endorsement of affirmative action.

The amendment’s strength is to reject the notion that a nation can exist as a set of discrete classes and proclaim that race is irrelevant to an individual’s equal status as a citizen. The colourblind institution of citizenship binds us with an identity that rises above the alphabet soup of diversity dogma. To be American or Australian is to be a member, something bigger than the sum of its constituent parts.

“Only that promise can allow us to look past our differing skin colours and identities and see each other for what we truly are: individuals with unique thoughts, perspectives and goals, but with equal dignity and equal rights under the law,” writes Thomas.

“What matters is not the barriers they face but how they choose to confront them. And their race is not to blame for everything – good or bad – that happens in their lives. A contrary, myopic worldview based on individuals’ skin colour to the total exclusion of their personal choices is nothing short of racial determinism.”

Nick Cater is senior researcher at the Menzies Research Centre.

It will take more than soaring rhetoric to reverse the slide in the polling. Anthony Albanese must say what the Indigenous voice will do, apart from make us feel warm and fuzzy.