Late last week, just days before the official reopening of Melbourne’s Holocaust Museum, a group of UN Human Rights rapporteurs accused Israel of genocide.

Even when set against the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the rapporteurs’ statement, which steers well clear of declaring Hamas’s goals and conduct genocidal, is laughable. In effect, as William Schabas notes in his authoritative treatise on Genocide in International Law (2000), making out a charge of genocide “requires the prosecution to establish the highest level of specific intent”.

But it is obvious Israel’s “specific intent” is not to exterminate the inhabitants of Gaza – had that been its goal, it could have achieved it with devastating speed by aerial bombardment, without endangering thousands of Israeli servicemen and women.

And the fact the claim is manifestly inconsistent with Israel’s unceasing efforts to warn civilians of impending military action, and encourage them to move to safety, only further undermines its credibility.

But the accusation’s absurdity is less surprising when it is considered in the context of the Genocide Convention’s troubled history. As Anton Weiss-Wendt shows in his two-volume study of the Convention’s early years, the USSR was intimately involved in its drafting, with Stalin (an undoubted expert on genocides) personally marking up the successive versions that led to the final document, which was approved by the UN General Assembly on December 9, 1948.

The result was a legal instrument the American Bar Association called full of “vague formulations that could be used against the United States”, but which plainly “lacked the teeth” to prevent the genocides carried out by authoritarian regimes.

Opened for signing as the Cold War turned especially threatening, North Korea’s invasion of South Korea on June 25, 1950 provided the Soviet Union with the first opportunity to test the new Convention’s propaganda value.

Almost immediately, China and the USSR charged that the US, instead of simply ensuring South Korea’s self-defence, was perpetrating a genocide that “overshadowed even the Nazi atrocities” by dropping bombs “stuffed with insects infected with communicable diseases” on North Korean schools, hospitals and refugee camps.

Those contentions were entirely concocted, as historians Kathryn Weathersby and Milton Leitenberg have shown. Far from suffering genocidal attacks, the North Korean regime, acting on Chinese and Soviet advice, had injected prisoners with cholera bacteria and then provided tissue samples from their corpses to supposedly reputable human rights investigators.

But despite their complete falsity, the claims were a propaganda triumph, fuelling massive anti-American protests worldwide. That success, which confirmed the shock value of accusations of genocide, cemented a pattern that was to be repeated time and again.

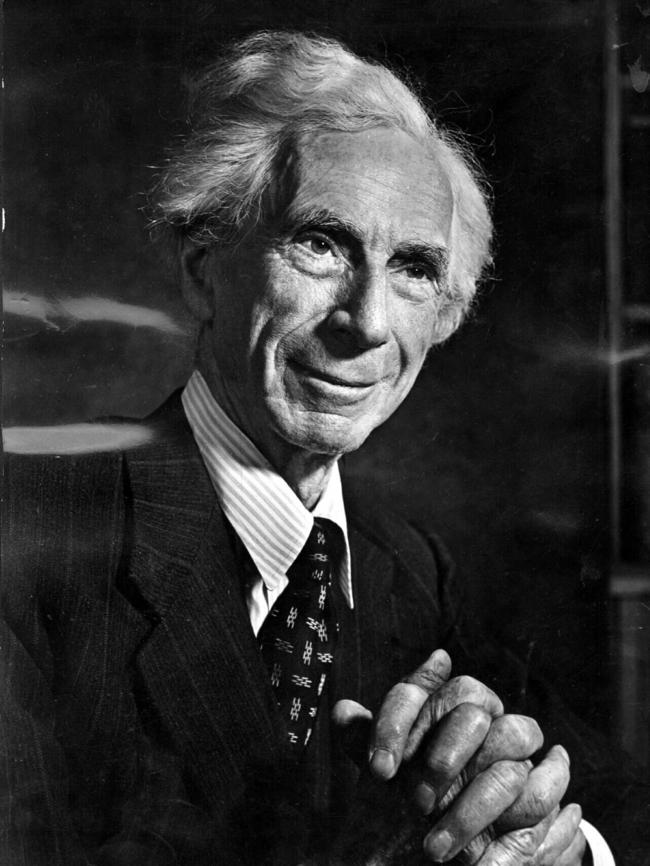

Central to that pattern was the use of prominent dupes. Behind his back, the Soviets ridiculed Bertrand Russell, who had distinguished himself in the run-up to World War II by suggesting that in the event of a German invasion, Nazi troops should be welcomed in Britain as “tourists”, since the manifold charms of the British way of life would take “the starch out of them”. But Russell and a bevy of illustrious lawyers, whose intelligence was surpassed only by their stupidity, unfailingly lent an aura of authority to even the most far-fetched allegations.

As that process played itself out, the claim that a “genocide” was under way, in any one of its “ecological”, “cultural”, “racial” or just plain “ethnic” varieties, was applied by a bewildering range of UN bodies and experts to over 80 countries, accounting for four-fifths of the world’s population.

No country, however, was targeted more relentlessly than Israel. Yet again, the Soviet Union under Stalin took the lead, first accusing Israel of perpetrating a genocide “no different from the Nazis” in 1950, just as the Arab League was threatening to renew its war of extermination against the Jewish state.

After that, the clamour never subsided: from 1948 to 1988, fully one-fifth of the articles in Pravda mentioning genocide involved accusations hurled at Israel.

Indeed, the last comprehensive Soviet study of genocide, published during the Gorbachev era, downplayed the USSR’s own crimes while accusing Israel of cold-bloodedly murdering Palestinian children by distributing bombs disguised as toys. And even those contentions, presented without a skerrick of evidence, paled compared to the claims of the Arab states and their fellow-travellers – claims in which the assimilation of Zionism to Nazism, and of Israeli leaders to Hitler, was always uppermost.

The aim of this propaganda blitz was clear: if Israel was itself perpetrating a genocide comparable to the Nazis’, it could hardly derive any moral legitimacy from the Holocaust. Rather, as an abomination, it deserved, like the Hitler regime, to be wiped out, justifying its enemies’ genocidal plans.

But the ultimate result of the strategy the Soviets pioneered, with its endless proliferation of genocide claims, was to rid the notion of its substance.

Winston Churchill, when he reported in 1941 on the atrocities the Nazis were committing in the western borderlands of the USSR, had called them “a crime without a name”. Now, the term, coined in response to his speech, remained, but it was a name without a crime. As Weiss-Wendt put it, “genocide” had become “a hollowed-out vessel that could be filled with any meaning” – once everything is genocide, nothing is.

The effect, highlighted by last week’s UN statement, is not only to distort public understanding of the contexts to which the term is recklessly applied; it is, even worse, to occlude the distinctiveness of radical evil.

War has always been, and always will be, a charnel house of blood and misery. But an unbridgeable gap separates its terrible suffering from the horrors of administrative mass murder – and, most obviously, of the Holocaust.

We cannot, nowadays, even come close to fathoming what was experienced by those the Holocaust sought to destroy. The all-consuming fear the prisoners in the camps had to swallow in order to continue to live; the constant prospect that one might at any moment be beaten, hanged, or shot; the aching hunger without any prospect of respite; the deliberate, calculated reduction of human beings to walking, crawling skeletons, suspended in the no-man’s land between life and death; and then death itself, industrialised, everywhere present, stripped of all dignity, shorn of all meaning.

Genuinely comprehending those experiences is impossible. And as they recede into the past, they risk becoming ever more abstract, ever more removed from our mental map. That is why institutions such as Melbourne’s Holocaust Museum, which allow us to stare genocide in the face, are of such importance. But it is also why the UN statement is so utterly pernicious.

By blurring the distinction between the radical evil that was shockingly on display on October 7 and the response to it, the statement legitimates an entirely false moral equivalence behind which that evil can shelter, strengthen and strike. There neither is, nor could there possibly be, any surer way of guaranteeing yet more genocides. And, in the Islamists’ tender hands, they will be the real thing.