New satellite images revealing the advanced militarisation of the Spratly islands, built by China, and Ross Babbage’s warnings of Chinese control of Australia’s approaches, add urgency to the need to understand where China and its relations with the US, especially, are heading.

Leading China analyst Jean-Pierre Cabestan, head of government and international studies at Hong Kong’s Baptist University, says Trump has decided to turn the tables on the pattern of the 21st century, and to have the US test the Chinese rather than vice versa, as indicated by his conversation with Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen.

Speculation is growing that the Trump team’s strategy is to go a step further and align itself with Russian President Vladimir Putin, a turn that several election contenders from the Right in Europe may wish to join. Such a manoeuvre, some claim, would leave China out in the cold, friendless except for the likes of North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un and Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte, a self-confessed murderer.

It may prove difficult next year for Xi to focus fully on responding, since his priorities will need to be domestic — getting the economic transition right, downgrading the debt crisis, arranging for his own cohort to move into the top jobs in the party-state apparatuses — in the lead-up to the crucial 19th Communist Party congress in October, which will determine China’s governance structure for a further decade.

Of course, that may deflate Trump’s disruptive strategy, since China may simply be too engaged in other priorities to rise to the bait.

And a Trump-Putin alliance may help drive some other important players closer to China, rather than attracting a consensus to “get with the strength” — especially if that alliance seeks to erode or dismantle international economic or security arrangements.

Beijing learned a lot during the global financial crisis, says Cabestan, including how to deploy the tools — a mix of repression and persuasion — to preserve social stability.

The urban middle class may feel at times irritated at being treated like children by authorities, but are not questioning the one-party hegemony. Those who do raise such questions — lawyers, journalists, civil society activists, academics — are by now almost all locked up for long sentences for “state subversion”.

Nevertheless, lack of confidence in Xi’s capacity to manage the huge, complex Chinese economy has helped drive the capital flight the government is trying to restrict, with foreign reserves falling more than $US1 trillion ($1.36 trillion) over the past 18 months.

Much of the key decisions in China are now being made in the secretive suite of commissions and “leading small groups”, whose ways of working, meeting dates, membership, decisions and powers are not revealed to the public. Many of the reforms flagged and welcomed early in Xi’s leadership remain yet to be implemented, says Cabestan — or appear stuck between apparently contradictory policy positions, such as the need to reform state-owned enterprises, yet also the insistence that they retain the commanding heights of the economy, and the moves to professionalise the judiciary while tightening the party’s control over courts.

Credit is especially given, however, to Xi for his radical shake-up of the PLA, modernising its technology, reducing its unwieldy numbers, separating out the three military services more clearly, shifting the structure from a regional basis to a central command to which core services and functions are accountable, and with Xi becoming commander-in-chief to which the three services, plus a new, powerful strategic support service, report.

The PLA has developed its first forward base, at Djibouti in Somalia, but remains naturally risk averse since it lacks war-fighting experience. “Keeping everyone in the dark about its use of force is better than using it and failing,” Cabestan says.

Xi still lacks sufficient support within the party of 89 million merely to impose his chosen personnel on the party. But whereas when he came into office four years ago he had to contend with substantial, semi-organised factions, he has presided over their fragmentation so that they only now coalesce, on occasion, around individuals — with policies almost never in play.

His anti-corruption campaign, prosecuted through the party’s Central Commission of Discipline Inspection, has played a major role in that divide-and-rule success. Critics dare not raise their heads for fear of attracting the CCDI’s grim attention, so they are merely waiting for a big slip-up.

Of course, this can happen in the international arena as much as domestically, so Xi will be keeping a close eye on how Trump transforms US power. He cannot afford to appear to be conceding ground to the US even while being too busy on domestic priorities to pursue fresh foreign forays. And China has yet to bed down convincingly Xi’s ambitious and potentially brilliant Belt and Road initiative, recreating the region as tributaries of Beijing.

Besides challenging international protectionism that threatens China’s economy, Xi needs to dismantle local protectionism that resists his centralising reforms. His strategy is to make the party present everywhere, and to position the centre to control the vast nation more efficiently in its real and virtual lives, by rolling out the new grid management and social credit systems.

The new elite he is installing ready for a power sweep at the party congress is bound by interests rather than policies. Some are like him — “red hearts” whose parents were party elders — but more are members of what is now being called the New Zhijiang Army, people who have worked alongside him, especially in Zhejiang province.

Arthur Kroeber, the editor of China Economic Quarterly, asks whether Xi will be able to maintain a steady course in the face of trade and other threats posed by Trump.

He says that “the possibility that East Asia will become the arena of a new cold war between the world’s two largest economies is a dismal one” for all of us.

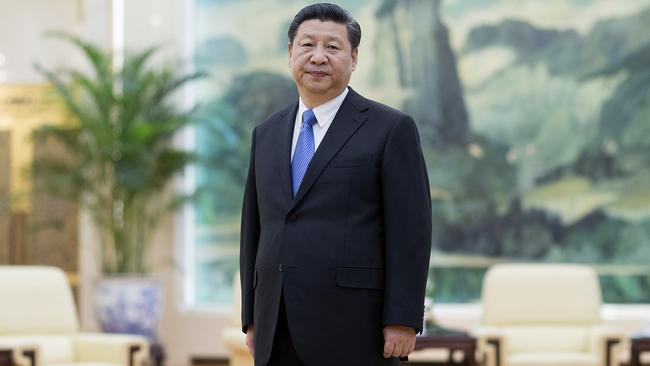

A battle is taking shape between the world’s two most powerful figures: Chinese President Xi Jinping, who aims to be a “core” of certainty, and disruptive US president-elect Donald Trump.