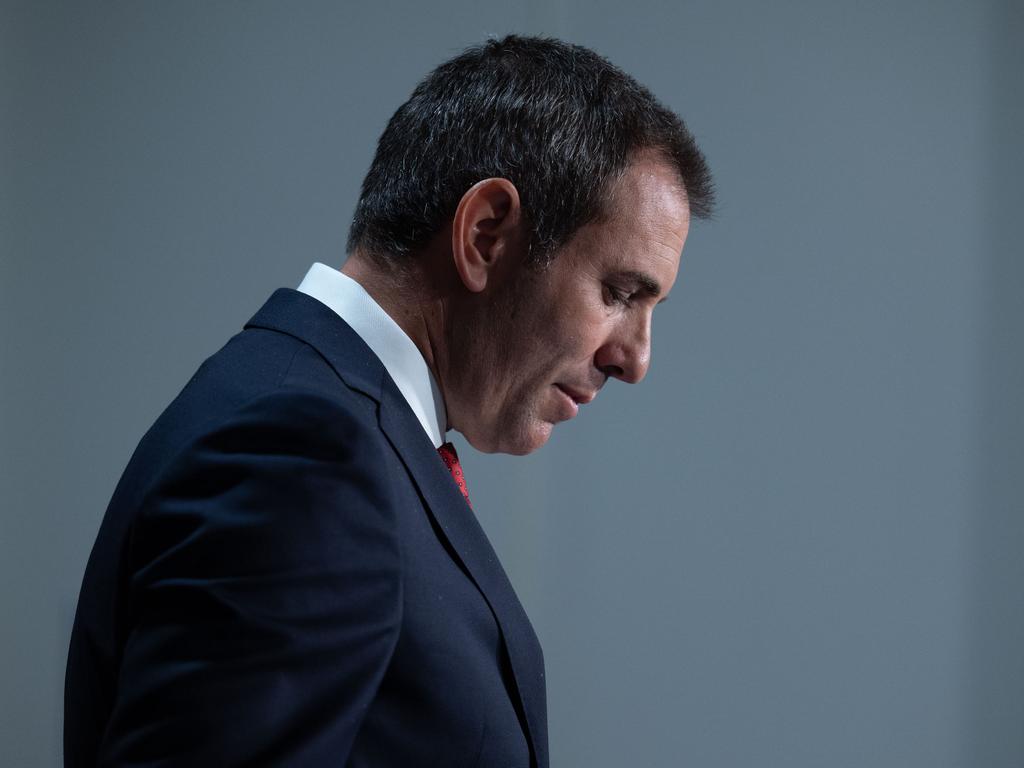

Nobody in Labor has done this for a long time. It’s risky. For many, it’s alarming. Chalmers has smashed the protective glass container in which the Albanese government presented itself to the world as a modest, “safe change” ALP government that wouldn’t rock the boat.

That was never realistic. Chalmers’s essay tells the world the 2022 election did more than terminate a decade of Coalition rule. It brought to power a Labor government that plans to introduce a new form of “values-based capitalism” for Australia.

Hang on. Anthony Albanese didn’t tell us that before the election – for the excellent reason it would have created campaign havoc. But governing is different. Chalmers, seven months a Treasurer, has taken it upon himself to offer a philosophical treatise to explain the meaning of the Albanese government (and probably inform many members of the government itself).

Chalmers has done three things. He announces that the world has changed fundamentally, that means Labor must change and he sketches the settings for a new Labor reform agenda for the decade of the 2020s. This is a big deal – for Labor, politics and the country. He hasn’t got it fully sorted. The qualifications run through the essay; for instance, Chalmers talks about “the beginnings of a new economic model”.

He knows the direction he wants. But uncertainties abound. “We’re trying to listen, we’re trying to talk straight, we’re trying to keep an open mind,” he writes. “But we’re also determined to lead, and I think we can see a framework of new economic models emerging already.”

Chalmers wants to help us make sense of the Albanese government. Maybe he wrote the essay to help clarify his own thinking. It emerges from his ambitions as Treasurer and his frustration on his discretion arising from a structural budget problem and an economy run by the central bank’s drive to beat inflation. He wants to break free from the straitjacket.

The essay is pervaded by Labor’s bedrock belief that only Labor possesses the reforming culture Australia needs. It is a case study in Labor egocentricity. Chalmers writes about the past, the present and the future. He upholds Labor’s historic mission but applies it in today’s new world. For Chalmers, laissez-faire is yesterday and austerity is not an option.

The intellectual origins of this essay are not new. The article updates the direction in which Labor has been moving for two decades. It abandoned long ago the market-based, Productivity Commission, micro-economic reform model that has dominated Australia’s economic debate since the path-breaking Hawke-Keating age. Labor decisively moved away from Keating after the 1996 election – since then the world has changed and Labor never went back.

From that time, Labor has opposed a more flexible labour market, rejected market-driven micro-economic reform, dismissed tax reform based on broadening the base and cutting the rates, Federation reform, shunned major spending cuts to achieve a surplus, promoted big government-led initiatives from Gonski, the NDIS and the NBN, and aspired to lead on climate change action.

Chalmers has now gathered up the main economic policies Labor took to the 2022 election, thrown them forward, and vested them with fresh lustre and new intent. What is his reform model?

It enshrines the energy and technology transition to renewables as a virtual centrepiece. He believes the market economy needs reform and must be better driven by government to social and environmental outcomes. He wants a resilient, supply-side economy, a growth agenda that prioritises equality and equality of opportunity, emphasises human capital and prioritises a co-investment model where public and private capital work together.

Chalmers bets the times are moving with Labor – given the clean-energy economy, the digital revolution and the growing emphasis on social outcomes. Every day he confronts the limits on the federal budget. He sees public-private co-investment as a contemporary version of Tony Blair’s Third Way. He thinks much of the investment class is moving with him, naming former Bank of England governor Mark Carney and former Macquarie Bank executive and Paul Ramsay Foundation chair Michael Traill.

He wants climate rating of firms to channel investment and a role for government in redirecting capital. The signals are there – the $15bn National Reconstruction Fund to boost advanced industry along similar lines to the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, the $20bn Rewiring the Nation plan, the $10bn Housing Australia Future Fund, and collaboration with the super funds to improve social investment.

This is reform far more politically acceptable than the harsh politics of the old market-orientated agenda. The zeitgeist is with Chalmers – it is hostile these days to free markets, globalisation and market-based reform. Chalmers will generate stacks of popularity for his vague but enhanced role for the state in capital allocation.

But it is loaded with risks and it is limited. Co-investment cannot transform our wage performance or living standards. It has a worthwhile role but will not reshape our economy.

Here’s the pivotal question: Will this new model actually deliver the productivity gains Labor needs? At this point it looks dubious. It is, moreover, wrong to imply our past policies contained no values. Labor has no monopoly on values. Australian public policy has long been built on a values foundation, mainly growth with equity.

Over the past generation Australia’s economic performance – essentially 30 years without a recession – is world-leading. In this period it moved up the income per capita ranking from 21st in 1992 to ninth today. Income per capita rose almost 70 per cent in the past 30 years. Household wealth grew ninefold.

While it is conventional wisdom within Labor to dismiss the Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison era as a “wasted decade”, that judgment lacks balance. Our economic recovery from the pandemic was among the best in the world. The unemployment rate at 3.5 per cent is the lowest in nearly 50 years. But our productivity performance lagged along with poor outcomes for real income growth.

“This tells us the system needs reinvigoration, not rewriting,” Business Council of Australia chief executive Jennifer Westacott said on Tuesday. ”We’ve dropped the ball when it comes to the reform needed to maintain a system that has actually left Australians much better off.”

Labor governed for only six of the past 26 years. It has little ownership of the framework it inherits. Chalmers should be wary about the forces he is unleashing. By attacking the market system, declaring Labor will shift to a different form of capitalism with values, but leaving the specifics vague, he invites others to put their interpretation on what he means. That’s a mistake.

Given that two of Labor’s most recent examples of government intervention – the reintroduction of multi-employer bargaining and caps on gas prices – will have damaging consequences in the marketplace, they invite people to conclude Chalmers’s essay means more of these policies. He needs to clarify.

The zeitgeist now is more assertive state power, an opportunity but a risk for Labor. Chalmers knows our history is choked full of state power follies. In his essay he said almost nothing about the central issues of budget repair, tax policy and productivity priorities – he needs to add a postscript. Fast.

Jim Chalmers has written an essay about the future, not the past. He is the first senior figure in the Albanese government to offer what Labor once did endlessly – put a philosophical framework around the policies of Labor in power.