We should be grateful for Scott Morrison’s leadership on the vexed issue of compulsory vaccinations. It is a touchy subject. The right to bodily integrity was recognised after the bitterest of experiences: the forced medical experimentations carried out by the German Nazi government.

There is room for disagreement on where the boundary lies between encouragement and coercion. The balance between individual rights and responsibilities towards others is equally fraught.

It seems reasonable to most people that a healthcare worker should be vaccinated, just as we expect them to wear masks and gloves. The question of whether the same rule should apply to supermarket attendants, car mechanics, journalists, horse trainers, cockroach poisoners and stump grinders, however, is one best decided by their employers.

The responsibilities of an employer under workplace safety laws are comprehensive and, where disputes arise, can be tested in court.

Given the importance of this debate, it is surprising there has not been more discussion about a decision by the full bench of the Fair Work Commission last week that is utterly germane. The commission had been asked to rule on a claim for unfair dismissal by a receptionist at an aged-care home in NSW who had refused to be vaccinated against the flu.

Two of the three commissioners hearing the case, vice-president Adam Hatcher and commissioner Bernie Riordan, concluded the woman’s dismissal was not unreasonable. Among the grounds offered for dismissing the case was that it would be against the public interest to grant the right of appeal.

The decision reads: “We do not intend, in the circumstances of the current pandemic, to give any encouragement to a spurious objection to a lawful workplace vaccination requirement.” The commission’s deputy president, Lyndall Dean, disagreed. In a lengthy dissenting judgment she says decisions to mandate vaccinations are a “lazy and fundamentally flawed approach”.

“All Australians should vigorously oppose the introduction of a system of medical apartheid and segregation in Australia. It is an abhorrent concept and is morally and ethically wrong, and the anthesis of our democratic way of life and everything we value,” Dean writes.

One doesn’t have to agree with Dean’s conclusions to recognise that she touches on issues of fundamental moral importance.

Her dissenting opinion is an important contribution to a vital debate we are doing our utmost not to have. The majority decision that there are no legal grounds to justify an appeal may well be right. Yet even the least vaccine hesitant among us must surely dissent from the notion that public discussion should be suppressed. The commission’s job is to regulate the workplace, not control public debate or insult our intelligence by implying that ordinary people cannot be trusted to separate truth from falsehood.

The logic for mandatory vaccination is unclear. The Covid-19 virus is so horrible, few Australians need to be persuaded the jab is in their own best interest. While the vaccines reduce the personal risk of severe illness or death, they do not appear to reduce the collective risk of the virus spreading in the community.

As Dean writes in her dissenting judgment: “The risk of spreading Covid only arises with a person who has Covid. This should be apparent and obvious. There is no risk associated with a person who is unvaccinated and does not have Covid, notwithstanding the misleading statements by politicians that the unvaccinated are a significant threat to the vaccinated, supposedly justifying ‘locking out the unvaccinated from society’ and denying them the ability to work.”

Dean refers to the advice from Safe Work Australia that employers cannot rely solely on a vaccinated workforce to minimise the risk of exposure to Covid in the workplace. She argues that testing employees is a far more reliable method for keeping workplaces safe. “Testing is now widely used around the world as a risk control for the spread of Covid. There is absolutely no reason why it cannot be widely used in Australia.”

Dean goes on to consider the human rights dimension to mandatory vaccinations. She examines the relevance of the 1947 Nuremberg Code and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which recognised the right to bodily integrity.

The freedoms we have surrendered in fighting this pandemic are not trivial. They include freedom of association and movement, freedom to protest peacefully and worship, freedom of commerce and freedom of Australians to enter or leave their country. We have lost freedoms so self-evident we didn’t even know we could lose them: freedom to grieve, to comfort and be comforted, to be beside our loved ones in sickness and health.

We have been promised that most of those freedoms progressively would be returned to us by Christmas if we stuck to the vaccination plan.

The people are sticking to their side of the deal. As of Sunday, 79.5 per cent of Australians in the most vulnerable age cohort, the over-70s, had been fully vaccinated. Well over half the entire adult population is in the same position.

At this point, premiers should be restoring liberties, not taking more from us. Yet every day, it seems, the Andrews government finds more freedoms with which to trifle and more areas of our private lives in which the state is willing to trespass. These are not the actions of a premier acting in good faith.

“It is the common fate of the indolent to see their rights become a prey to the active,” Irish orator John Philpot Curran wrote in 1790. “The condition upon which God hath given liberty to man is eternal vigilance.” Especially, it seems, in Victoria.

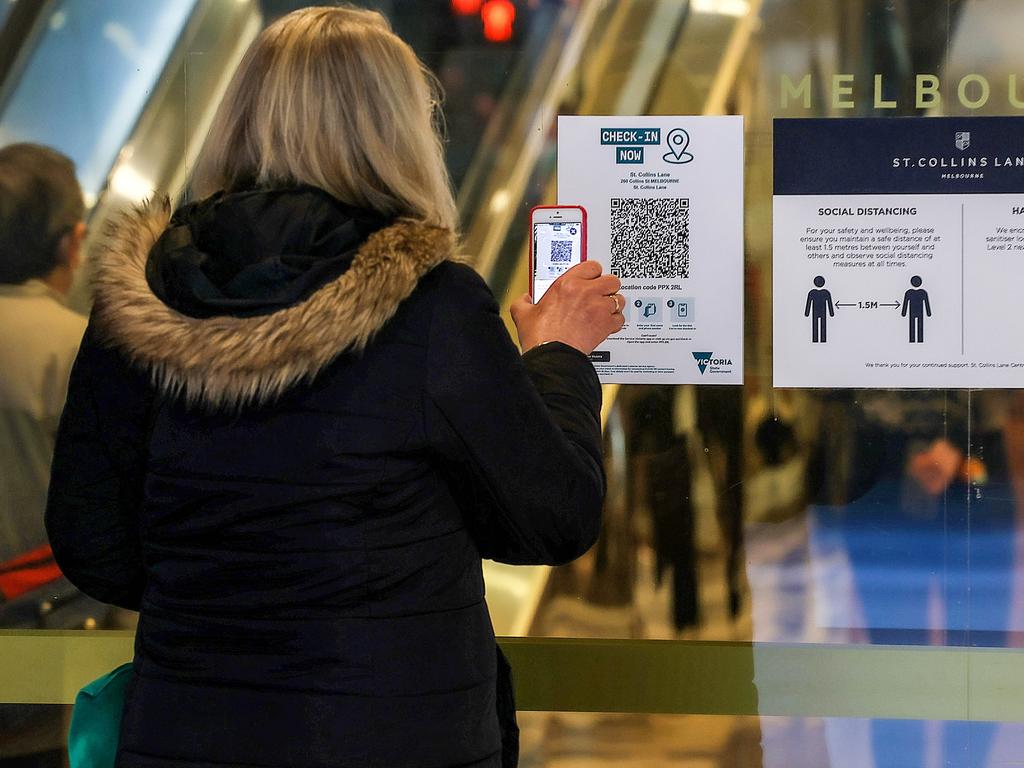

Last Friday Daniel Andrews made vaccinations all but compulsory in Victoria, although he did not put it in those terms. Instead, his chief health officer issued an extensive list of occupations where workers would need a jab to go about their business. Trappist monks have not been included as far as we can tell, but from Sunday week only vaccinated priests will be allowed to preach, provided it’s on Zoom.