Sadly, whether it is the cost of living, the grind of modern professional life, or fertility conditions many Australians face substantial challenges to starting a family when they want to.

For some, it has already been placed entirely out of reach. These challenges are being felt hardest by women in their 30s, if the insights from my friends and family are any guide. Yet there is a dearth of policy solutions being offered to prospective parents, especially concerning the access and affordability of increasingly essential fertility treatments.

Australia’s birthrate sits at 1.6 babies per mother, below the rate required to ensure population replacement let alone stable growth. Successive governments have largely ignored this problem because, from a population point of view, it has been assumed that immigration can sustain Australia’s population growth.

It is often also assumed that Australia’s low birth rate is a normal consequence of modern Australians choosing to have fewer kids than past generations, especially because of greater career and educational equality for women.

But for many this doesn’t feel like a choice at all.

Male fertility has plummeted, halving since the mid twentieth century at the same time that there are manifold barriers for prospective mums. The hustle of professional life, the expectation of completing higher education and the perils of modern dating mean that most women now in their 30s spent their 20s working hard to figure out what they wanted in life and building a career.

In the decade in which they are most biologically suited to have kids, it’s the last thing many would consider. Meanwhile, young people need better access to education about fertility and parenting. For most, we cease getting sex education in high school, leaving most of us fairly uninformed about fertility health during our 20s. And when one goes to look for reliable information it is surprisingly inaccessible. A healthy young person thinking about whether or not they want to be a parent shouldn’t have to spend upwards of $90 to a GP to be get basic advice on maintaining their fertility health.

Young women and couples are landing in their 30s, finally feeling just secure enough to think about children and, despite being healthy, are finding that due to a multitude of conditions falling pregnant isn’t as easy as they assumed.

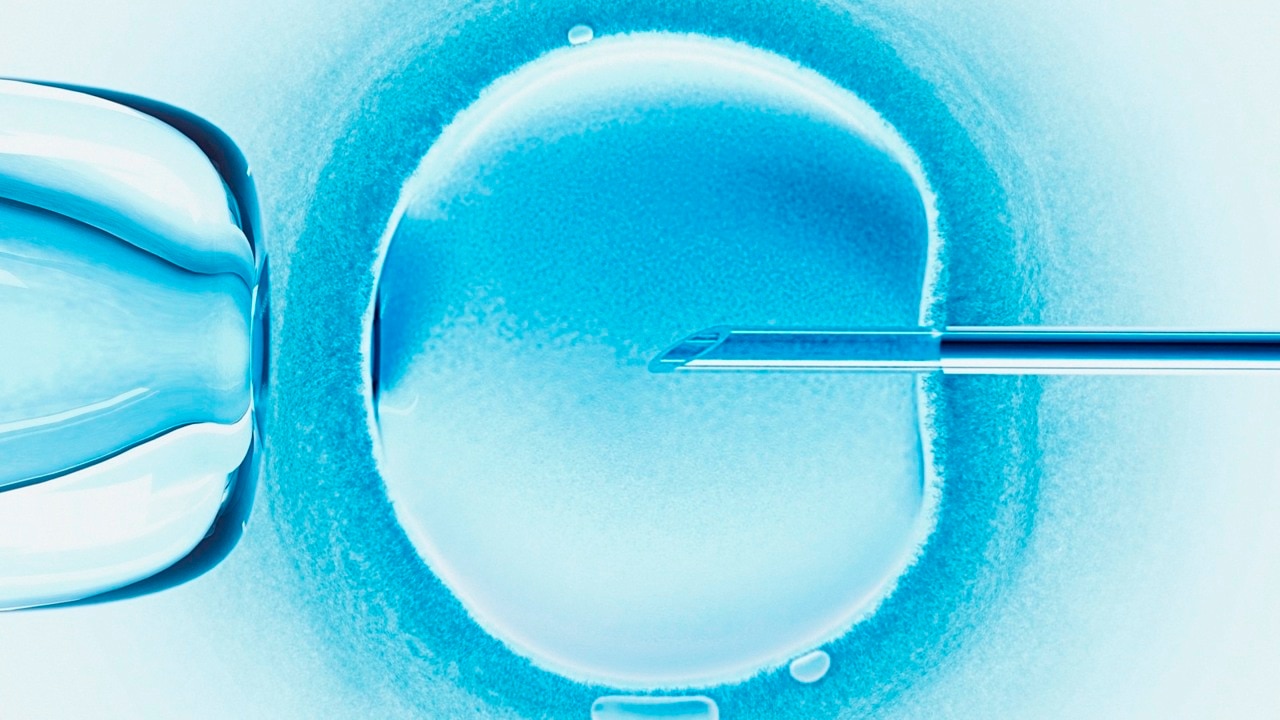

For these Australians fertility treatments, especially IVF, are a godsend.

But these therapies aren’t just about those who want to be parents but can’t; it’s also about those who simply want to maintain the choice. I know plenty of women who think they don’t want to be a mother, but nevertheless want to maintain the option, just in case. For them egg-freezing is an excellent insurance policy and a tool for long-term life planning.

Despite these miracle treatments being more commonly needed, there are cost and education barriers that are unacceptable given how essential this assisted path to parenthood is for the modern Australian family. Even accounting for Medicare assistance, the cost of a single cycle of IVF can leave patients out of pocket by $6,000 or more, plus other expenses. And that’s if only one cycle is required. Egg-freezing has a lower upfront cost but requires hundreds of dollars a year in ongoing charges. Meanwhile, women and men often don’t know enough about these options and fertility generally and so can miss their ideal windows to engage with such treatments.

For people trying to save a house deposit, or simply contending with other costs of living, it can be a bitter choice between the chance to be a parent and financial security.

While the macro pressures on parenthood – housing, cost of living – will take time to ease, policymakers need to think outside the box to start reducing immediate barriers. Subsidises could be explored to cover more medical expenses.

Targeted fertility education could be offered through unis, TAFEs, or workplaces to address the knowledge gap among men and women about their fertility health. Salary-sacrificing, early access to superannuation, or low-interest HECS-style loans could be explored as mechanisms to help young women and couples engage in egg-freezing while they’re studying or focusing on their careers.

It’s clear that the way Australians are planning for parenthood is being fundamentally changed and disrupted by fertility treatments. Yet our policies don’t reflect that these therapies are now essential to the future of the Australian family.

New measures are required to increase the affordability and availability of fertility treatments if the dream of the Australian family is to be kept alive for the next generation.

Urgent policy experimentation is needed to ensure the dream of the Australian family remains open to all. We should live in a society where those who want to be parents experience the fewest obstacles possible to growing families at the time of their choosing.