Already he’s looking like the most consequential president since Ronald Reagan – except that while Reagan’s determination was to beat evil empires, Trump’s current inclination seems more to do deals with them.

When Trump threatened a 25 per cent tariff against American allies Canada and Mexico but only a 10 per cent tariff against American strategic foe China, that should have been a final wake-up call to all US allies that the global Atlas was sick of carrying the rest of the world on his shoulders. To their credit, both Canada and Mexico were finally roused to do what they always should have: better police their border with the US.

What’s now happening with Ukraine is a consequence of the long-term neglect by America’s European allies of their own military strength and shameless free-riding on a US that they’re much happier to lecture than to help. Trump’s agitated posts that Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky “started the war”, is a “dictator” and is continuing the war only to keep on the American “gravy train” do not reflect reality – but they do reflect Trump’s understandable frustration with allies that are more of an encumbrance than a force multiplier.

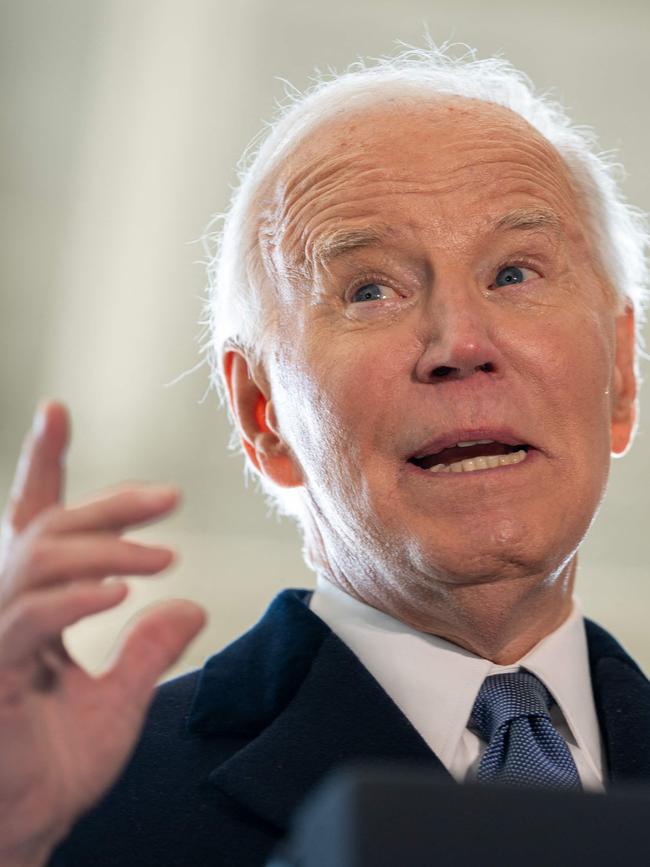

It was Joe Biden’s America that did enough to stop the Ukrainians from losing but not enough to enable them to win – but that reproach applies even more to the Europeans, who gave about two-thirds as much, only their help was more economic than military.

Along with many millions in his political base, Trump resents what he claims is $350bn spent by his predecessor to support a distant country in a far-off war without ever really explaining what was at stake. And if we’re honest, in all the worthy forums where officials talk about what “we” must do to solve some global problem, the real burden is always shared on to America.

In flagging a substantial troop presence to police any Ukrainian ceasefire, even the British Prime Minister, leading the West’s next strongest country, seemed to insist that it would require an American backstop.

Yet because the US no longer revels in being the indispensable nation but resents it, Britain would have to do more heavy lifting than at any time since the Falklands or the days of the British Army of the Rhine for any Ukraine ceasefire to be more than a pause before the Russian dictator resumed his march.

I doubt the new US President really wants to surrender the long Pax Americana under which, until very recently, the world was richer, freer, fairer and safer for more people – in exchange for a darker world where the strong do what they will and the weak suffer what they must – if only because Trump would hardly relish portrayal as the loser who betrayed Ukraine to Vladimir Putin, as Neville Chamberlain betrayed Czechoslovakia to Adolf Hitler.

Likewise, even a deal with one dictator to leave Ukraine a Russian colony need not mean a further deal with another dictator to give China a free hand over Taiwan, because the consequences of a new world disorder would be endless military jostling plus the proliferation of nuclear weapons to smaller countries that might be tempted to use them in an existential struggle.

Since 1945, the US is the one country that has been readiest to stand sentinel to others’ freedom, to do as much for others as they were prepared to do for themselves, often without the honour it deserved for being the policeman that a freer and fairer world will always need. And it’s possible that, far from surrendering the responsibilities that go with strength, the Trump Ukraine ploy may turn out to be a clever piece of political theatre, finally forcing European leaders to level with their voters about the need to do more for their own security.

One explanation for Trump’s evidently greater sense of solidarity with Israel than with Ukraine could be respect for a warrior nation that has never taken its survival for granted and never ceased striving for strategic and military self-sufficiency.

On this score, though, Australia, Canada and even Britain, which partly relies on the US for its nuclear deterrent, resemble the Europeans more than the Israelis.

With a militarist dictatorship desperate to turn Ukraine into part of Greater Russia; a communist dictatorship itching to seize Taiwan as its next move to avenge the “century of humiliation” and restore China as the world’s “Middle Kingdom”; an apocalyptic Islamist dictatorship still burning to wipe Israel off the map and desperate for nuclear weapons before turning its attention from the “little Satan” to the great one; and quite a few other countries imagining they’ve been ripped off by the West and eager to see it fall, these times could hardly be more dire.

After so much rhetoric from Western leaders about these times resembling the late 1930s, deeds must start to match words. Across the Anglosphere and the wider West, a defence industrial base does now need to be mobilised.

The compounding folly of net zero any time soon, gender fluidity and the cultural angst of the best countries on Earth must forthwith cease. Some form of national service, if only to remind young people that citizenship is a two-way street, needs to get under way. And China needs to be eased out of critical supply chains and critical technology partnerships so that any champions of freedom don’t find their systems suddenly turned off.

Rather than rail against the only leader the free world has, America’s Five Eyes allies, with whom the instinctive bonds of solidarity remain deep, should become much better at offering the great republic more practical help.

Perhaps if Australia, Britain, Canada and New Zealand (the CANZUK countries) could build an informal but vigorous strategic partnership of their own (noting that we’re already all linked in the Trans-Pacific Partnership) our leaders might be taken more seriously in Washington rather than dismissed like the errant governor of some potential 51st state.

In 1914, Australia volunteered to stand with the mother country “to the last man and the last shilling”. In 1939, we did our “melancholy duty” to support a Britain otherwise alone against the Nazi might. And there has never been a subsequent American war that we failed to support, less from cultural affinity than from the conviction that freedom and justice are the universal yearnings of mankind.

Of course, there is an alternative to renewing alliances built on a shared history and values cherished in common. Australia could opt to become an economic colony of China. But in that event, our paymasters in Beijing would hardly allow us a freedom that their own people lack. As last week’s live-fire exercise off our coast shows, Beijing’s expectation is that its clients “tremble and obey”. Soon enough, we would find that without strength, neither peace nor freedom lasts very long.

Tony Abbott was prime minister from 2013 to 2015. This piece was based on remarks he delivered to the Danube Institute forum in London.

There has been a lot to cheer in Donald Trump’s first month in office. He has sacked diversity hires, declared there are only two genders, swept away politically correct censorship and pulled out of the Paris Agreement, saying climate change is a hoax.