It was 1990 and I was in the office at The Canberra Times when the phone on my desk rang and I answered.

“Is that Chris Uhlmann?” a menacing voice growled.

“Yes,” I said.

“Well, Winchester got it in the back. But you’re going to get it in the neck. In the neck. Do you hear?”

The “Winchester” he was referring to was assistant police commissioner Colin Winchester, who was assassinated by a gunman in the driveway of his Canberra home in January 1989.

Before I could respond the caller hung up. Perplexed, I wondered what to do. It was late and the most senior person in the building was the news editor, Bob Ferris. Bob was pushing up against the deadline to get the paper away and it was obvious he wasn’t in the mood for a long conversation.

When I told him about the call he did, briefly, appear concerned before glancing back at his computer screen. An unfinished headline beckoned.

“Probably a crank,” Bob shrugged and returned to work.

Clearly, it was an empty threat but everyone in the building industry was paranoid about something and it was rubbing off. There was ample reason for paranoia; the story I had just published was about a Building Workers’ Industrial Union organiser whose backstory included serving three years for attempting to rob undercover drug squad officers and assaulting a policeman.

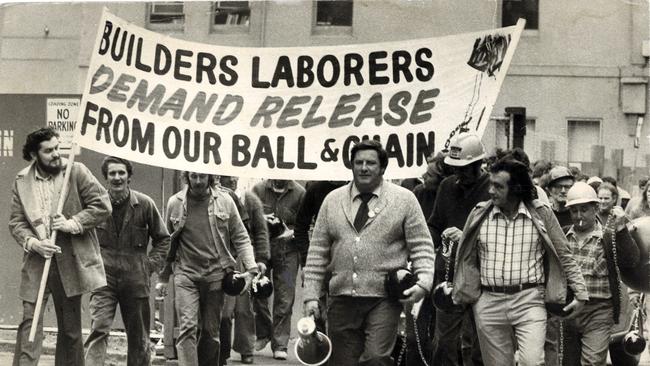

He was just one of the colourful figures who populated ACT building sites at a time when there was a bitter turf war between the rising BWIU and the remnant Builders Labourers Federation.

In the wake of a 1982 royal commission the BLF had been deregistered federally and in Victoria, but it still had branches in the ACT and Queensland.

It’s worth revisiting what royal commissioner John Winneke said about that union. “It has paid scant respect to the duties imposed upon it by the general law of the land, civil and criminal alike,” he wrote. “Under the pretext of ‘promoting the interests of its members’ this organisation has, with frequency, resorted to tactics of violence, intimidation and victimisation.”

Adding fuel to the fire in the early ’90s was the push by then ACTU secretary Bill Kelty to amalgamate the myriad craft unions into powerful super unions. The BWIU would join with the Federated Engine Drivers and Firemen’s Association and the United Mine Workers Federation in 1992 to become the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union. The BLF would pass into history.

My interest in the building industry coincided with another royal commission, this one called by NSW premier Nick Greiner and led by Roger Gyles QC. The inquiry did not cover the ACT and, for about six months, my journalistic ambitions rested on getting it extended to the territory.

Canberra was abuzz with rumours about rorts, corruption and intimidation on the six-year-long build of the new Parliament House. Somewhere in the suburbs pools had allegedly been paved with parliamentary marble and houses built with commonwealth cash.

The real hotspot was next to Lake Burley Griffin, where what was known as the Quadrant site became one of the most strike-plagued projects in Australia. At one point unions shut it down for 21 weeks in a row and in the first 18 months of the project its planned 20 storeys did not rise above ground level.

Two things about that time stick to this day: how frightened people were to put their names to accusations; and how much information was shared between the unions and some of the big builders. It was as if the union and construction bosses workshopped talking points with the punchline being, “nothing to see here”.

The Gyles royal commission was never extended to the ACT but when the 5000-page report was released in 1992 it recommended the deregistration of both the BWIU and the NSW Master Builders Association.

Gyles told a familiar tale of “nothing less than industrial anarchy in which any pretence of the rule of law or the application of principle has been abandoned”.

“The law of the jungle prevails,” he said.

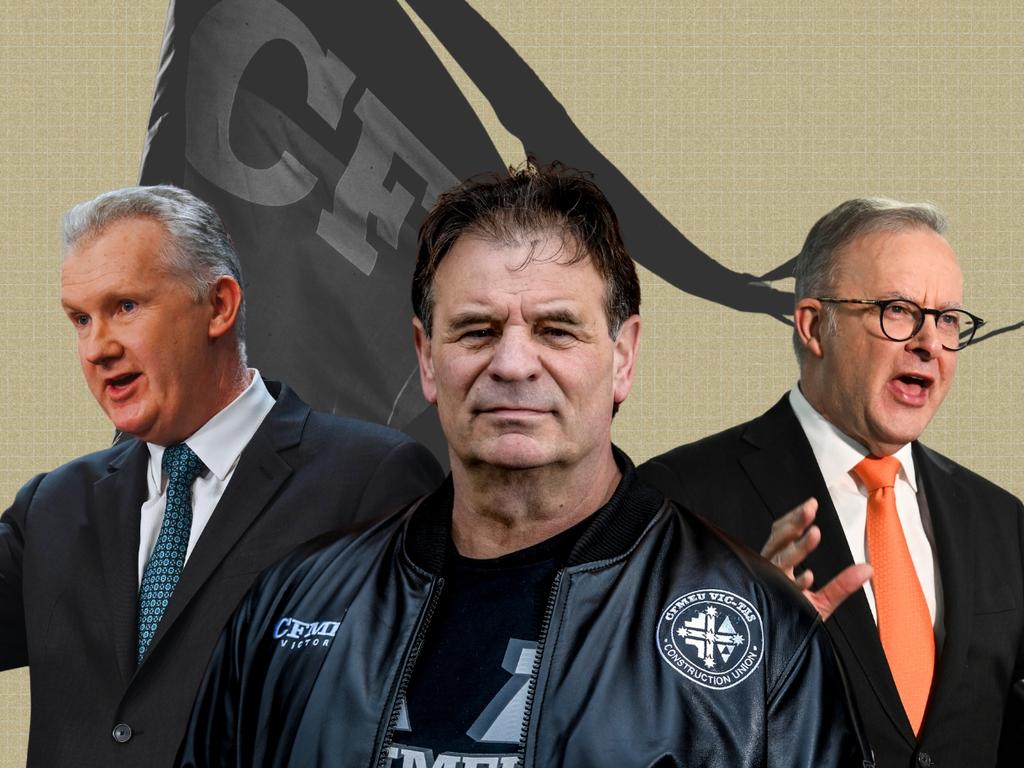

Thirty years later, reporting led by peerless investigative journalist Nick McKenzie has, once again, shone a light into the dark places of the building industry. He has found evidence of kickbacks, violence and outlaw motorcycle gang members as union delegates.

In correspondence with this column businesses have repeated some of the claims.

Again, no one wants to be named because of the fear of violence. One businessman claims he had “a CFMEU delegate tell me to my face they know where my kids go to school. It doesn’t get much more horrific or intimidating than that”.

One contractor says he puts site leadership through training with ex-SAS officers “so they can cope with bullying, intimidation, abuse”.

There are real-world consequences for all taxpayers, with industry groups estimating the construction union’s near veto power over building sites adds between 30 and 50 per cent to costs.

So, in 40 years since the royal commission into the BLF it appears nothing has changed except the names of the unions and officials.

This raises an obvious question: Why have the Victorian, ACT and federal Labor governments been so keen to entrench the power of the construction union when its nature was hiding in plain sight?

Victoria has imposed rules for procurement that grant the CFMEU extraordinary powers to influence those able to tender for large construction projects.

In the ACT, companies that tender for procurement must hold a valid Secure Local Jobs Code Certificate. Without a certificate, you can’t work on ACT government sites, even as a subcontractor. A council advises the minister on the operation of the code and the secretary of the CFMEU is one of three union officials who sits on that council.

Federally, within a month of the Albanese government being elected it defanged the Coalition’s building industry watchdog.

In the wake of the latest building industry scandal Labor is heading for the exits and expressing surprise and alarm. The deep question that needs to be asked is what ministers knew about how the construction union was operating when they passed laws that directly benefited the CFMEU. Were they wilfully blind or tacitly complicit?

Royal commission anyone?

The only death threat I ever received was while working on a series of stories about the building industry.