None of us understood what they were talking about until one of the joyous group explained they had discovered that day that they were now legally allowed to drink alcohol without having to obtain their citizenship rights.

Halls Creek at the time was a magical place; it had few opportunities but also little crime. In fact the town’s crime rate in 1967 was below the state average; domestic violence, child abuse and youth suicide were unheard of, mainly due to functional two-parent families. Aboriginal stockmen were the backbone of the beef industry and with their RM Williams boots and cowboy hats were the Michael Jordans of the day.

When I look back on that day and the cry “We are free”, I cannot help but lament the enormity of those three words. I wonder if it was the start of a process that has locked many of my people in a downward spiral and a self-imposed prison we are still unable to escape from.

The patterns that upheld the norms and values that maintained our families for thousands of years started to come apart, slowly at first but gathering pace; a pace no one, or no amount of money, seemed able to stop.

The reason this was happening to Aboriginal people in the Kimberley was the introduction of the basic wage, the mass redundancy from pastoral stations that followed, and the introduction of social security payments and alcohol. These factors caused a tidal wave of change in a very short time that affected the most vulnerable members of society, with catastrophic consequences.

The biggest loser was the Aboriginal male. From a proud man vital to the only industry in the Kimberley, and the foundation of Aboriginal families for millennia, he was relegated to a beggar who had to go cap in hand to his wife who, if they had children, received more money in benefits than he did.

With limited education, no job and no role or purpose in life, he had no economic status in his family and was no longer required by the industry he had built. As a consequence domestic violence increased to terrible proportions, as did the Aboriginal prison population. Fractured families increased and the number of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care grew exponentially.

Indigenous people currently receive $32bn a year in aid to solve these problems, but there is no real solution in sight. There have been many policies and strategies over the years but, despite the goodwill of governments and an army of dedicated service providers, little has changed. There are, of course, many Aboriginal families who have done well – mine included – but many more who haven’t.

I know we cannot turn back time and recapture the magic of Halls Creek and other small towns around 1967 Australia. But we can rethink our strategies and how we help Aboriginal Australians share the nation’s wealth. After 55 years of trying everything to close the gap, to little effect, maybe it’s time we give Aboriginal people a chance to give the decision-makers some advice through a voice.

It is a fundamental truth that the building blocks for all great societies are strong families that have discipline and structure, based on routines that produce positive outcomes. This is the principle of the path and, with few exceptions, all those who follow the path will succeed.

Many of our communities are struggling with overwhelming social issues and we cannot pull ourselves up by our bootstraps, as the advocates of self-determination believe, and we will require leadership from within and outside.

The voice could be an advocate in such circumstances, providing advice to government on what it could do to create the social and economic environment that enables families to succeed.

The voice proposal does not infringe on the rights of other Australians, nor should it. It is a genuine attempt to right many wrongs and create the mechanism to allow Aboriginal Australians to initiate strategies they feel will make a difference for their people. You could describe it as a mechanism for increasing their involvement in the democratic process.

How it is implemented is crucial to how effective it will be; that is why I believe we do need broad political support and involvement in shaping the voice. To continue to deliver programs as we have done since 1967 is akin to moving the deck chairs on the Titanic.

We must change the direction of the ship, as it is costing huge amounts of money, affecting lives and damaging the future of countless innocent children who deserve a better life than we currently offer them.

There are no simple solutions to achieving real change: some decisions will need to be made that will not be popular or achieve immediate results. Maybe Australia has come to a fork in the road in its relationship with Aboriginal people, and we need to consider what outcomes we would like to see 50 years from now?

If we don’t do anything different from what we have done previously, nothing can change.

If you live in regional Australia the issues that are creating divisions in the community are not based on political structures in Perth or Canberra but the growing incidence of crime and anti-social behaviour. These things I believe are symptoms of wider issues, but unless we create a mechanism to listen to the voices who say we must do something, nothing can change.

The two questions I believe Australians should consider at the referendum are “What should we do?” or the more empowering question, “Who do we want to be?”

I hope our answer to the second question will lead us to the conclusion that if most of the things we have tried in the past have not worked, and if we would like Aboriginal people to enjoy a better life, we will support the Indigenous voice to parliament.

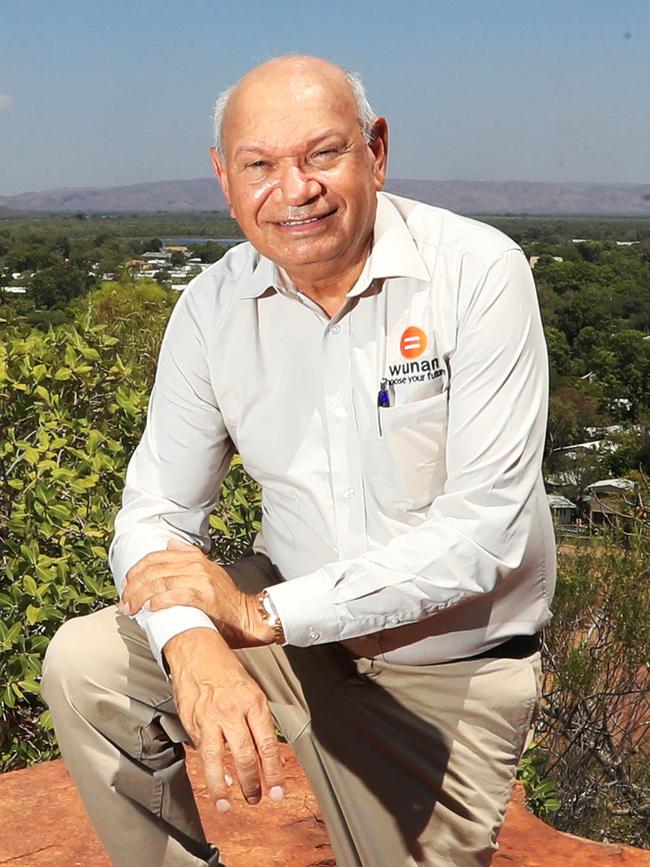

Ian Trust is chairman of Empowered Communities.

It was 1967. I was 16 and walking with friends to the basketball court in Halls Creek, an old goldmining town in the far north of Western Australia. I had just finished school in Wyndham and was holidaying in my former home town. We passed a half-dozen Aboriginal people who were walking to the local hotel shouting, “We are free, We are free!”