Telling voters that his wife, Jen, explained to him why an alleged rape in a ministerial office should be treated as a matter of grave concern was a cheap, folksy tale that backfired because it was insulting to women — and men.

It was on par with the Prime Minister claiming he doesn’t hold the hose when there are bushfires, and he’s not a police commissioner when it comes to rape allegations. He misses the point every time about what is required of him.

Be informed, very informed. On that score, it was foolish of him not to read a dossier sent to his office and written by a woman who has alleged that Christian Porter raped her when they were at high school.

If Morrison’s own office keeps these serious matters from him, why would Linda Reynolds feel comfortable coming to him about an alleged rape in her office. A political strategy of plausible deniability does nothing to support women in parliament.

For too long, people working in Parliament House have traded on, and suffered from, a bogus myth that this workplace is so different from others that normal rules don’t apply. I hate to break it to the Canberra mob, but you are not that special. Rules that apply in well-run workplaces should apply especially in parliament, to model best practice for the country. And that starts with complex issues such as allegations of sexual assault landing smack bang on Morrison’s desk. As any good chief executive knows, the buck stops with him or her. Not even the PM is so special that he can duck these issues.

To be sure, changing a workplace culture takes time. But here are 10 things the PM could do now to get that process started.

First, the PM could walk into the chamber today and propose normal work hours, say 9am to 6pm, in parliament. When parliament brought forward the end of the business day from 11pm to 8pm, its work got done. Be innovative. Encourage greater efficiency in less time. The federation won’t collapse. And MPs, especially those with little children, can have more normal lives while in Canberra.

Second, give MPs a proper lunch break with no divisions during that time so MPs don’t have to explain their absence and seek a pair for a potential vote. One woman mentioned having to make up stories so as not to reveal harvesting eggs at lunchtime. In the 21st century, no one needs to explain what they do at lunch.

Third, alcohol. Get rid of it. No workplace should be a place for a piss-up, especially when it comes to the people’s representatives. Instead of allowing MPs and staff to self-medicate with alcohol, reduce the sources of stress. Introduce zero tolerance for drunks and drunken behaviour anywhere in Parliament House, whatever the hour. Breath-test and drug-test workers in Parliament House to make it clear that the boozy culture there has come to an end.

Fourth, reform question time. Make it more civil, more meaningful, along the lines of the UK where a minister is allocated a QT session to deal with their portfolio. Political points are still scored, and more policy detail explored. In Australia, the most watched parliamentary proceedings are an ugly blood sport premised on disrespect where each side aims for maximum humiliation. Only the loudest, most aggressive voices, invariably macho ones, make the evening news. Politics will always be a combat sport, but there are ways to rein in the vulgarity. This is one.

Fifth, establish uniform and clear rules, and reporting lines, for every MP’s office. There are effectively 227 small businesses operating in Parliament House with every MP’s office a law unto itself. This is ridiculous. Getting rid of the archaic, opaque and tangled mess in place could lift standards very quickly. There should be one set of workplace rules laid out clearly for the whole of Parliament House, enforced by a central body. Every worker should understand the system, so that rules are enforced. Being elected should not equate to an entitlement about workplace behaviour. MPs are not that special.

Sixth, review the parliamentary privilege that applies in every MP’s office. The Australian Federal Police can turn up in any workplace across the country with the right warrants to investigate a matter — except an MP’s office. Combined, the Parliamentary Privileges Act 1987 and a Memorandum of Understanding with the AFP create special rules for MPs that are vague, largely untested and provide an unwarranted shield. National security concerns can be dealt with separately. Parliament House should not have an ambiguous protocol that not even MPs understand, and may abuse.

Seventh, the psychological services in Parliament House are a joke. Taxpayers are forking out for a contract that offers “confidential counselling” to MPs and their families by a company called Benestar. The Australian has been told few MPs know about it and, at least prior to COVID, “no one has used the service”. Fix that, please. People need to be genuinely supported in the workplace.

Eighth, stop mouthing sweet nothings in our ears. It is simply not enough that the Minister for Women, Marise Payne, has a spokeswoman who says that the senator “works every day on matters of concern for women”. What has she done? More to the point, how can she act without the PM’s support?

Ninth, no more silly distractions. Remember when Morrison became agitated and antsy when a journalist used the phrase “bonk ban” to describe Malcolm Turnbull’s new policy to end relationships at work. A bonk ban was a poor substitute for dealing with the harder issues. Neither Turnbull, when he was PM, nor Morrison now have moved on what matters.

Tenth, party leaders could instruct their MPs today that spreading rumours about the sex lives of female MPs, and their female chiefs of staff, and their female staffers must end. It’s not OK just because their work is politics. I’ve had senior ministers contact me wanting to share gossip about their colleagues’ sex lives. It speaks volumes about them, not their target. Former minister Kate Ellis will have more to say on this and other matters in her book, Sex, Lies and Question Time, to be published in a fortnight.

We can all drive change. Staffers should not have to keep sexual secrets for their bosses. That is not normal. We, in the media, especially those in the press gallery, can also change our behaviour. Many senior male and female journalists complaining about a toxic culture in Canberra now have been there for decades. What did they do to change that? Instead of wanting to be players, getting on the turps with MPs and staffers, soaking up the gossip in corridors, they could politely say: “No. Not interested. I have work to do and so do you.”

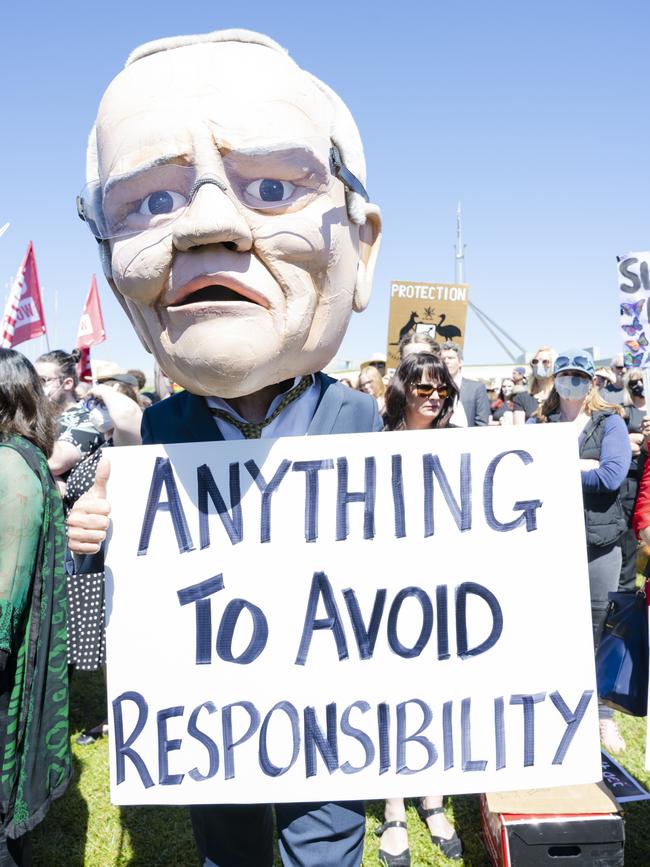

The Prime Minister faces an uphill battle to convince Australian women that he is the man to make Canberra a safer place for them. His performance to date has been woeful. Scott Morrison has an unfortunate tendency to refer up, like a branch bank manager looking for someone else to explain things to him, and leaving it to others to make the hard decisions.