Taiwan’s election will cast ripples across the globe

President Tsai Ing-wen, of the Democratic Progressive Party, is stepping down after her constitutionally limited two terms, so voters will chose from incumbent Vice-President Lai Ching-te, Hou Yu-yih, from the KMT, or the third candidate, Ko Wen-je, of the Taiwan People’s Party.

Much of the campaign has been fought over issues familiar in Australia, including housing affordability, low wage growth and gender politics. The candidates’ property investments have been a notable negative campaign issue.

Relations with China have also been critical in the election, as always. There are important differences between the candidates in policy and rhetoric towards China. However, with a consensus in the electorate that rejects Beijing’s non-negotiable position of unification under the One Country Two Systems formula, they have limited room to manoeuvre if they want to get elected.

There are common political themes with Australia, but the intensity of Taiwanese democracy is on a different level. The parties hold huge rallies in the weeks before the vote that are choreographed like rock concerts, with tens of thousands of supporters.

Campaign trucks with loudspeakers drive around the cities and there is a relentless pace of local campaign events for the legislative candidates. The televised candidate debates run for over two hours, followed by hours of commentary.

This intensity comes partly from history. The long struggle for democracy through the 20th century, beginning during the Japanese colonial period in the 1920s and through the authoritarian era to the 1980s, means the Taiwanese see democracy as a transformative modernising force. It also creates a deep well of symbolism and rhetorical styles that energise the democratic process. The DPP is fond of baseball references as an upbeat way to tell the story of modern Taiwan. The KMT sometimes uses the legacy of Chiang Wei-shui, the Japanese colonial-era democracy activist, to balance its historical legacy in China. All parties use food and temple culture in their campaigns.

Also, in a stark difference to China, Taiwanese politicians use the range of Taiwan’s spoken languages and their full expressive potential to persuade and mobilise the electorate in stump speeches and interviews.

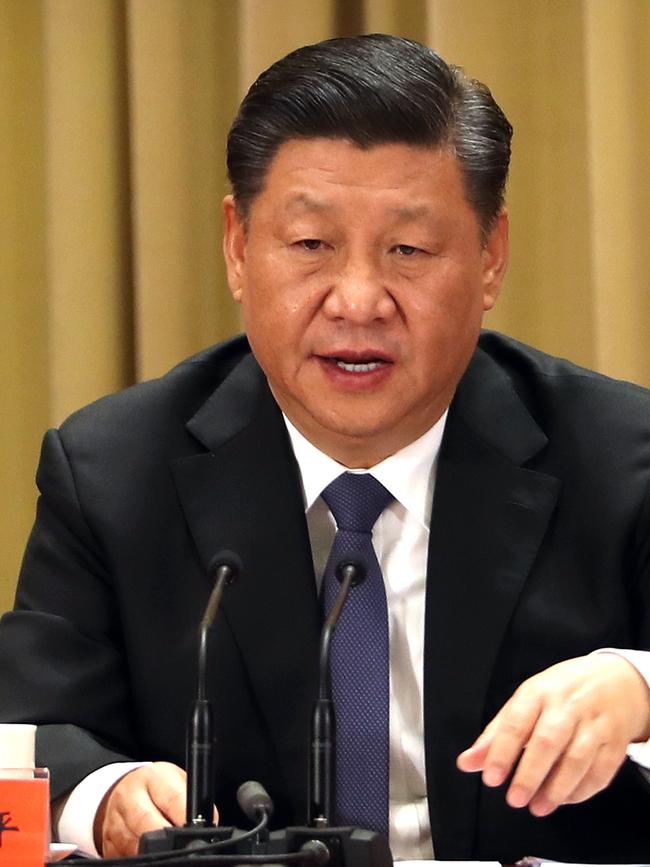

The KMT’s Hou Yu-yih will slip, seemingly inadvertently, between Mandarin Chinese and Taiwanese, sometimes in the same sentence. China’s leadership in contrast, uses language – only ever Mandarin Chinese – to assert unchallenged power.

The intensity of Taiwan’s democracy is also at stake. Beijing threatens Taiwan militarily and constantly issues statements about the inevitability of what it calls “reunification”. The Taiwanese understand this outcome means the destruction of the political, social and cultural institutions they have built over decades in the name of Taiwan.

It would not be right to say the complexity of Taiwanese politics and society is not understood in Australia. Australian media outlets relocating correspondents to Taipei instead of Beijing after 2020, including this masthead, has ushered in a golden era of outstanding reporting of Taiwan, as good as any in the world, by Australian journalists from across the media landscape.

Australian policymakers, politicians and policy analysts, however, are generally behind the media. Although there are parts of the policy apparatus in defence and foreign affairs, and individuals in the major parties with deep Taiwan knowledge, there is a tendency in policymaking and public life to see Taiwan as a proxy for broad themes of great-power politics. Taiwan is treated as an “issue” in the US alliance and China trade, rather than a place with a uniquely complex history and a politics of its own.

There are loud voices in Australia’s public life who use Taiwan simply to litigate the US alliance. This matters because whatever the election result, it is likely that the notable domestic political quietude of the Tsai Ing-wen era will not continue.

A three-way race will produce a less unequivocal winner compared to 2020 and the new make-up of the legislature will mean critical decisions by the government around defence, energy and international relations might be shaped by domestic politics in ways that may be easy for external observers to misinterpret.

This means Canberra must be proactive in finding opportunities to let Taipei explain domestic political developments. So too must Canberra listen to diverse voices on Taiwan – the Taiwanese-Australian community, Tokyo as well as Washington and Beijing, and Taiwanese people outside Taipei. Taiwan’s style of democracy is well-established but Canberra still needs to build familiarity with Taiwan to understand a different tone to its politics under a new president.

The regional security outlook is deteriorating, and so strengthening our own national capacity to respond with agility, nuance and assuredness to events in Taiwan and in the Taiwan Strait is more important than ever.

Mark Harrison is senior lecturer in Chinese studies at the University of Tasmania.

This weekend Taiwanese voters go to the polls to elect a new president and legislature.