Share benefits of capitalism or risk liberal democracy

The moral philosopher, Adam Smith, famously said more than 200 years ago: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”

This is perhaps the most meaningful quote in economics; and perhaps the most misused. It is the basis for Smith’s “invisible hand” of market forces that can keep the economy running well. Smith was clearly in favour of market forces, and not government, guiding decisions on, say, where and when to invest. Some think this means Smith was advocating for governments not intervening in the market economy in any way at all, which is wrong. Smith in his writings was clear that market forces and price signals, indeed his “invisible hand”, cannot bring the desired outcomes without companies facing competition, and it is a key role of government to ensure we have competition.

It is, I think, also not widely understood that the essence of well-accepted corporate strategy theory and practice is for companies to seek to gain market power. Profits from “outrunning” many competitors by aiming for better products are usually small and/or temporary as prices are set by the market where many players are competing fiercely. Alternatively, profits from exercising market power are large and continuing because, with the degree of freedom provided, companies can achieve prices above competitive levels.

In Michael Porter’s famous 1979 article, he described how companies generally actively seek market power through lowering competition, raising entry barriers to would-be competitors, or gaining some continuing “hold” over consumers. And when companies have market power, they should seek to protect it.

Warren Buffett has repeatedly said he only invests in companies with “moats” around them. He means companies that are in significant ways protected from competition. Company actions and objectives are therefore often at odds with the approaches and objectives of antitrust, and with good public policy. When companies seek to lower competition by a merger, or seek to block competitors, it is no accident. It is what they actively seek to do because it is the way towards higher profits.

Some believe businesses only succeed by looking after the interests of consumers. This is naive; it ignores market power. Companies must have regard to their consumers. The level of attention companies pay to their customers will, however, usually depend on how much competition they face.

All businesspeople know that when the number of competitors gets too large price competition is often the result, and that this “destroys shareholder value”; or, alternatively put, helps consumers. With a small number of stable competitors each company is aware price competition will simply lower prices across the board and not benefit any company; so prices remain high and stable.

New entrants will seek to grow share by lowering prices or product innovation and must be kept out by the existing players by raising entry barriers or acquiring the new entrant early. There are many forces against policies that promote competition. Business and business organisations, and often business media. Progress in improving competition is like walking up the down escalator; if you are not pressing forward you will go backwards.

Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator for the London Financial Times, has written: “What has emerged over the last 40 years is not free-market capitalism, but a predatory form of monopoly capitalism. Capitalists will, alas, always prefer monopoly. Only the state can restore the competition we need.” This is the essence of what Adam Smith was saying. Far from the “invisible hand” suggesting the government should not intervene in the market place, there is a crucial role for government to promote competition. As Wolf said, liberal democracies are under threat from the consequences of a lack of competition, particularly that the benefits from capitalism are not being properly shared. It must be said encouraging people to pursue their self-interest is not the most obvious way to run a society. But it works as it creates prosperity. It will only be able to do this in a democracy if the wealth is reasonably evenly divided. Some who want to keep wealth unequal have realised democracy can no longer serve their interests.

I embrace capitalism, as it generates prosperity, and can do more. But it must come with rules ensuring competition, and there must be policies to redistribute some of the wealth created. We should harness the power of incentives and innovation to solve significant problems: a carbon tax would do wonders for harnessing capitalism to tackle climate change.

We need stronger merger laws and a law against unfair practices, as they have in the US, UK and most of Europe, if our market economy is to yield the benefits it should.

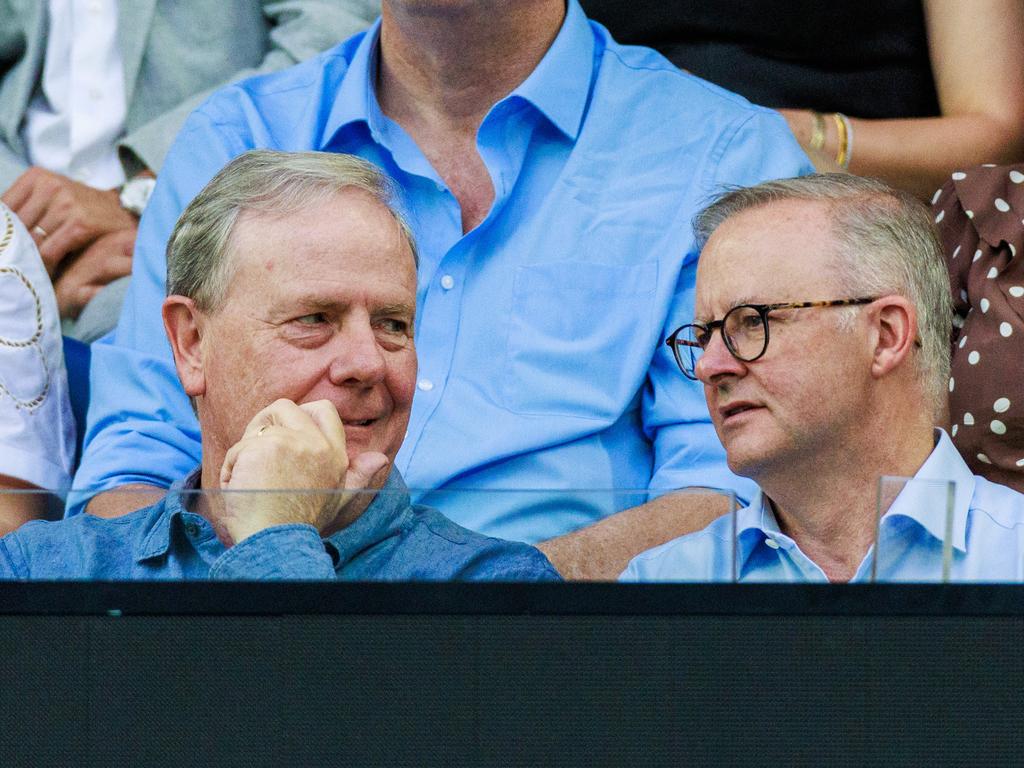

Rod Sims is former chair of the ACCC. This is an edited version of an address at a seminar organised by the universities of Sydney and Queensland.