Secrecy is the curse in this fiasco. Morrison’s swearing himself in to five separate portfolios in addition to being prime minister meant a deception of the public, the parliament and most of the ministers involved.

Anthony Albanese is engulfed in a synthesis of genuine outrage and unique political opportunity. He accuses Morrison of “an extraordinary and unprecedented trashing of our democracy” – and Morrison is wedged, under fierce assault by the Labor government while facing a reaction of dismay, anger and bewilderment from his own side.

The fortunes of the Liberal Party and the Coalition have sunk even further. Albanese is rolling out evidence to show unconventional and untrustworthy behaviour orchestrated by the former prime minister in response to the pandemic. He wants to damage the Liberals for years. The core problem is Morrison’s conception and concentration of power during the pandemic.

Aware of his vulnerability Morrison is defending himself but saying to his colleagues that, for any offence, “I apologise”. It won’t assuage many dismayed colleagues. It was a blunder of political and personal relations for Morrison to swear himself in to their portfolios without telling finance minister Mathias Cormann, home affairs minister Karen Andrews or, incredibly, his trusted deputy leader and treasurer, Josh Frydenberg. Unaware that Morrison also was sworn as treasurer, Frydenberg spent late last year deflecting pressure from some Liberal MPs to challenge his unpopular leader.

The juxtapositions are beyond weird. So for the 12 months before the election Australia had two treasurers, Morrison and Frydenberg, but Frydenberg didn’t know, nor did the public, parliament or cabinet. This is because Morrison took no decisions, got no briefs and played no role as treasurer. He was the invisible treasurer and, with one exception, invisible minister in the other four portfolios.

But if Morrison – resources portfolio apart – didn’t take any decision, then surely the entire model was unnecessary and unjustified. An argument can be mounted at the start for Morrison to be sworn in as health minister along with Greg Hunt. But beyond that the argument for Morrison to assume the other four portfolios is weak and unpersuasive. Yet the damage is immense. Any way this is assessed, the damage is out of all proportion to the benefit.

Morrison justifies his actions as a “break glass in case of emergency” safeguard. But Morrison’s fallback mechanisms have an organising principle – they invariably mean an increase in prime ministerial power or potential power. The revelations on Tuesday suggest a cabinet that barely functioned during the pandemic and a prime minister who called the shots but, apparently, with inadequate advice from the Prime Minister’s Department.

The reality is that Morrison, surely, was able to extend this model only because it was secret. Would the cabinet, let alone Cormann, Frydenberg and Andrews, have tolerated these collective arrangements had they known? Surely not.

Two issues now arise – legality and actual decision-making. Morrison says all his moves were legal, constitutional and followed due process. The Governor-General, with full documentation, authorised everything. But Albanese has asked the Solicitor-General for a legal opinion that will be delivered next Monday. This is pivotal.

Will this opinion cast a legal doubt over Morrison’s actions and the authorisation provided by the Governor-General? If so, this will become an inflammatory situation. “If there was any legal problem I wouldn’t have done it,” Morrison has told colleagues. Government House has been quick to say the GG, David Hurley, acted on advice but added, significantly, the decision whether to publicise appointments was a matter for the government. So far, there is only one known decision Morrison made as a portfolio minister – to cancel an oil and gas exploration permit off the NSW coast given sitting Liberal MPs needed the cancellation to protect their election prospects. This was not a cabinet decision; it was a decision for the resources minister, Keith Pitt, who had a different view to Morrison.

So Morrison used his separate authority to get the result he wanted. Morrison, acting as resources minister, pre-empted the resources minister. This is unconventional in the extreme and a breakdown of ministerial responsibility. Did Morrison take any other decisions? Morrison says “no”, this is the “only matter” where he made such a portfolio decision.

Yet Morrison’s defence of acquiring the portfolio powers in relation to Treasury and home affairs is unconvincing – he calls it a “belts and braces” approach given the pandemic’s future was difficult to predict.

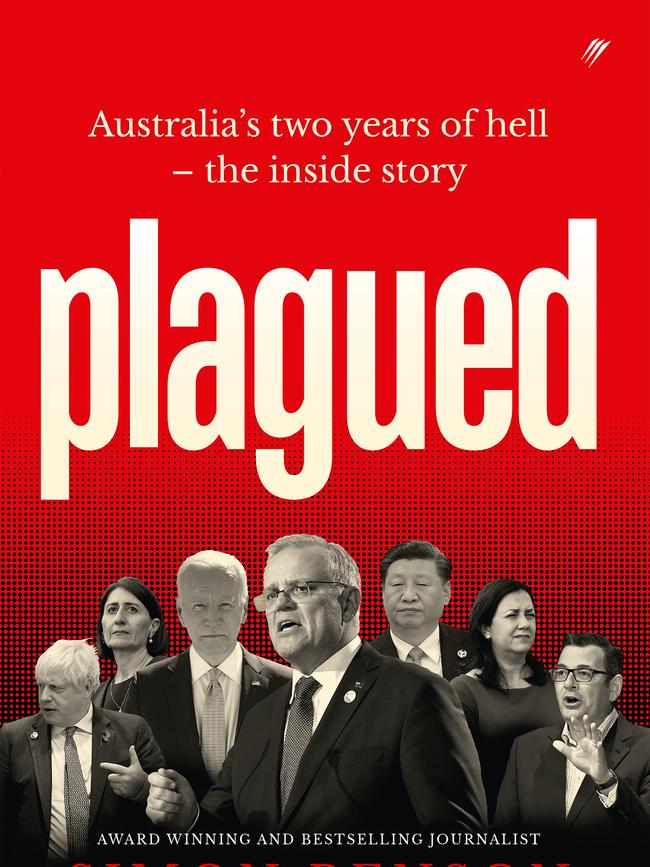

By his complete rejection of the Morrison tactic Albanese will need to explain how he thinks the health dilemma should have been managed. As the Simon Benson-Geoff Chambers book Plagued makes clear, the problem facing the Morrison government in early 2020 arose from the drastic consequences of invoking the emergency powers of the Biosecurity Act. When health minister Hunt and attorney-general Christian Porter examined the act they were gobsmacked.

“How did the parliament ever pass this?” was their reaction. The act gave the health minister virtually unlimited powers, non-reviewable by courts or parliament, powers probably greater than a war minister, with the Benson-Chambers book saying Hunt saw it as “up there with the divine rights of kings”. The 2015 law should never have been passed in this form. Porter devised written protocols to govern Hunt’s use of the powers. But Morrison wanted more checks and balances.

The solution they devised was to swear in Morrison as health minister to safeguard against one minister having such unacceptable power. Hunt supported the move. The Governor-General got a separate briefing about the “human biosecurity emergency” the government might need to declare.

Sources said on Tuesday that Morrison told the national security committee of cabinet about the dual ministerial arrangement. The mistake seems obvious: the decision should have been publicised. It would have been accepted by the public with ease. Critically, Porter gave his advice as a “one-off issue” in relation to the Biosecurity Act dilemma.

The key to the entire saga seems to be that Morrison, once the model was established in relation to health, then applied it to unlock other problems he thought might arise in the portfolios of finance, home affairs, Treasury, and industry, science, energy and resources.

Albanese said “no explanation” satisfies the swearing-ins. “I cannot conceive of the mindset that has created this,” he said. But Albanese is now PM. The Biosecurity Act is his responsibility. Does he support the law in its current form? Maybe he does. If not, what solution would Albanese recommend?

At this stage there seem to be two areas for reform – changing the Biosecurity Act and ensuring that any changes to ministerial arrangements must be gazetted or made known to the public, parliament and executive.

But this issue has a long way to run as more material and facts emerge. While Andrews called on Morrison to quit the parliament, a by-election is the last option the Liberals need now.

It is the secrecy, deception and absence of visibility around prime ministerial power that has brought Scott Morrison undone.