But the Greens have managed to do so by insisting on including the right to disconnect amendment. It purports to protect employees from the bombardment of work-related emails, texts and phone calls outside office hours. It’s real effect, however, is far more insidious.

Knee-jerk responses to confected moral panics are generally a bad idea, particularly when they lead to ambiguously worded laws that apply indiscriminately with little regard to the nature or size of the business.

While out-of-hours interruption might be annoying for some, others will recognise it as reassurance that their work is valued by their employer. Either way, it is better to let responsible adults work things out between themselves rather than glue yet another layer of compliance to the Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes No. 2) Bill, a cornucopia of red tape that acts as a disincentive for jobs and a catalyst for inflation.

The disconnect amendment is a victory for the anti-work ethic which has been gathering strength since the Covid-19 panic. It is inspired by the secular delusion that work is merely a means of earning a living rather than the purpose of living itself.

Like the Greens’ demand for a four-day week, the right to disconnect hinges on the seductive narrative of restoring the work-life balance supposedly disrupted by the pressure of modern life. Work is scapegoated as the problem, as an unnecessary burden and a source of stress, rather than the key to personal fulfilment and shared prosperity.

The compulsory closure of workplaces and the glorification of social distancing triggered a destructive change in workplace culture that has become permanently entrenched in the public sector. It created a laptop class with special privileges denied to other Australians who faced the choice of working from work or not working at all.

One of its most pernicious offshoots was the phenomenon of quite quitting, meeting the minimum requirements of one’s job with no more time, effort or enthusiasm than absolutely necessary. The right to disconnect is its natural corollary.

The Morrison government tried to force public servants out of their pyjamas, wean them off Zoom meetings and return them to the office. It had little success.

Last July, long after any serious threat from Covid-19 had vanished, the Community and Public Sector Union bamboozled The Australian Public Service Commission to agree to some of the most generous work-from-home rights in the country for 174,000 bureaucrats across 103 commonwealth agencies.

It empowered every APS employee to make a flexible work request, including permission to work from home. The agreement barred agencies from limiting the number of days employees could work away from the office.

Instead, they were obliged to “lean towards” requests, presuming they were obliged to wave them through. This extraordinary change in workplace practice, far older than the commonwealth public service itself, occurred without any consideration of its long-term effects or the consequences for public sector productivity. Little attention was paid to the effects on organisational culture, staff morale, information security and increased technology costs.

Instead, it was blithely assumed by those within the Canberra bubble to be a very good thing, making it easier for women and Indigenous Australians to compete in the workforce.

A clause in the agreement gave First Nations people the right to request flexible working on the grounds of connection to country and to fulfil their cultural obligations.

The soft-headed assumptions justifying the mass disconnection from work are challenged in a new book by David L. Bahnsen, the founder of the US-based private wealth management firm The Bahnsen Group. He confronts the modern sacred cow of work-life balance, describing it as “a poorly phrased euphemism for asking someone to work less, think about work less or care less about work.”

He says the habit of working together in an office was part of a spontaneous order that coalesced over a long period. It allowed employees to collaborate, connect and communicate in a way that furthers a business’s mission. It was an efficient means to share ideas, debate points of strategy and react to challenges in real-time.

Bahnsen bluntly states the obvious: employees are less accountable when working from home. People are less productive when they don’t have established work hours. Far from enabling personal fulfilment, it increases alienation, erodes corporate culture and fragments workforces. It robs workers of the sense of reward that comes from celebrating victories and working through obstacles in physical proximity.

Instead of encouraging a more inclusive workforce, it benefits an exclusive few at the expense of the many. When increased anxiety, loneliness and isolation is being blamed for a rise in mental instability among younger workers, the destruction of office life cuts them off from another source of face-to-face interaction. It reduces the opportunity for mentoring and teaching workplace culture. All to increase their wellbeing, reduce stress and improve their lifestyle.

“We know what is really behind the mentality of work-from-home, and it is not a call for more productivity, creativity and innovation,” writes Bahnsen. “The reality of human nature is on my side here. Businesses and workers that embrace the time-tested value of collaboration and daily presence will come out the winners.”

Productivity arguments in favour of working from home are hard to sustain. After a spike in productivity in the first half of the Covid-19 emergency, productivity went into free fall from the middle of 2021. The decline was arrested in the September quarter of last year, but it was largely because of reduced working hours, not greater workplace efficiency.

The argument for a return to conventional working arrangements is at least being heeded in the private sector, where profit matters and productivity is more easily measured. In the US, Goldman Sachs has announced a crackdown on laggards, reminding employees of their obligation to be in the office five days a week.

Citigroup and JP Morgan Chase & Co have been tracking attendance using data from entry cards. Citigroup recently told staffers they may face consequences, potentially affecting pay, if they don’t comply with attendance policies.

Elon Musk, one of the most vocal opponents of the work-from-home movement in the corporate world, told Tesla administrative workers in an email: “If you don’t show up, we’ll assume you have resigned.”

Musk draws attention to the hypocrisy of social justice laptop warriors supporting measures that may benefit themselves but are profoundly socially unjust. Working from home has never been an option for manufacturing staff at Tesla.

Women who work at supermarket checkouts continue to balance their work and family commitments as best they can around their shifts. They bear the cost of getting to work and childcare on smaller salaries than a Canberra public servant.

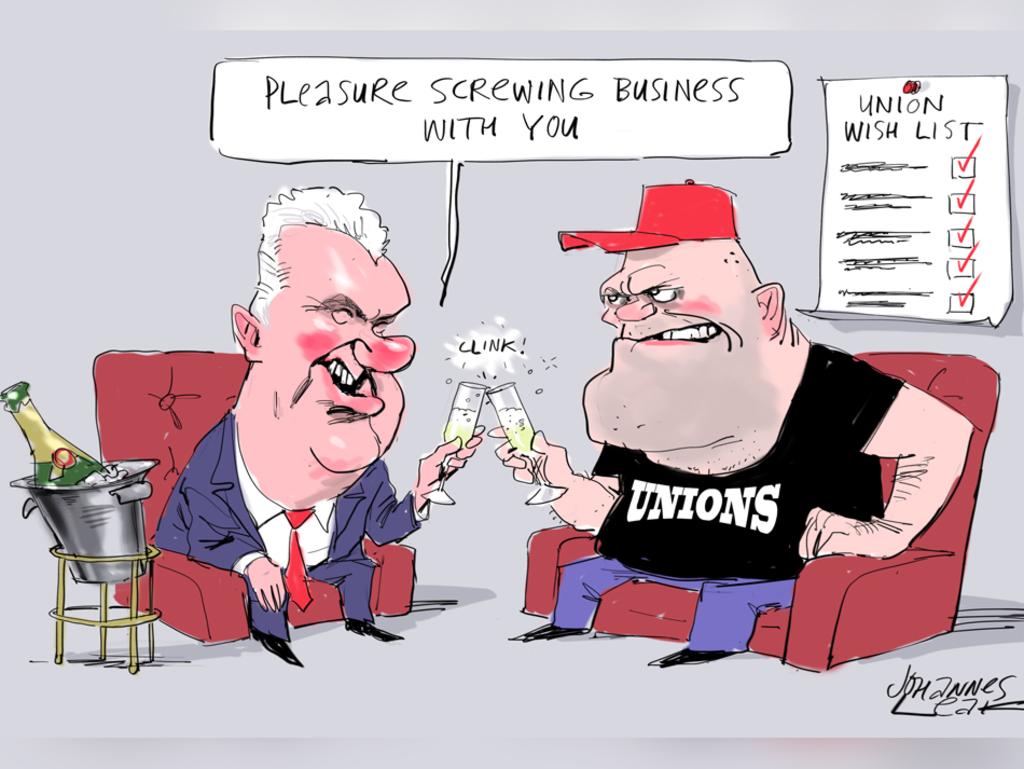

On Sunday, Peter Dutton honed in on the economic consequences of outsourcing workplace policy to the Greens. He was right to draw attention to the damage to business, the added pressure on inflation and the unemployment rate. Yet the conservative critique of industrial laws must go beyond mere economics and confront the progressive assault on the value of work itself.

Work is much more than an economic activity for most people. It is a source of purpose, meaning and identity. It bestows dignity and social obligation on individuals. It offers the reward of what Arthur Brooks described as “earned success”, the inner satisfaction that comes with proof that our service is valuable to others.

Conservatives must push back against the progressive delusion that a workless existence can ever be acceptable or that inequities can be overcome by increased dependency on the state.

A pro-work ethos will drive measures to encourage Australians to work for longer and review the policy settings that shoehorn workers into retirement at an age when they still have much to contribute. We must revisit the meaning of retirement after a century of rising life expectancy. Workers in their late 50s or early 60s should be able to look forward to something other than a 25-year holiday.

A pro-work government should tackle welfare reform, recognising that the best form of welfare is a job. It will confront the dominance of academia in post-school education to encourage more young people into trades and the caring professions.

It must firmly reject the utilitarian view of work as a means to an end and recognise its higher purpose. Reinvigorating the work ethic will do more for social justice than any number of economic interventions by the state.

Nick Cater is a senior fellow at the Menzies Research Centre.

A week ago, it was hard to imagine a less appetising piece of legislation than the dog’s dinner of a workplace bill the government dished up to parliament at the end of last year.