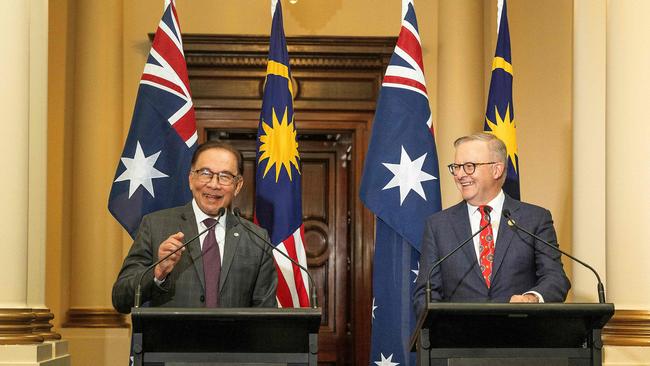

The Philippines will not yield one inch of our sovereign territory to any foreign power, Marcos thundered, concerning Beijing’s incursions into waters around The Philippines. By contrast, Anwar declared: “If they (the US) have a problem with China, they should not impose it on us; we do not have a problem with China.”

Anthony Albanese essentially talked but said nothing in response to both leaders.

Australia’s position with ASEAN over China, pre the Albanese government, was perfectly fine. It still is, unless Canberra decides to solve a problem that doesn’t exist and thereby creates a new one.

Let me explain. Here’s a hot scoop. The 10 member nations of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations have already been tipped off to the news that Australia is a longstanding strategic and military ally of the US, and that we have quite a lot of problems with Beijing’s regional behaviour.

Generally, ASEAN wants Australia to maintain its strategic identity, though not all of them can always say so publicly.

First, let’s pause to pay tribute to Marcos and Anwar. They both represent real democracy. Marcos overcame the once negative legacy of his family name to resoundingly win a democratic election. He’s a much better president than Rodrigo Duterte was and he has restored strategic stability to Manila.

Anwar is one of the most determined and courageous figures in Southeast Asia. He spent years in jail on trumped-up charges of sodomy. His life is a triumph of democratic activism. That’s not to say that both men haven’t said and done things over their careers that Australians would find difficult.

But let’s be frank, ASEAN is diverse and internally divided. Recognition of this is its great strength, Its monumental achievement, through relentless and exhausting diplomatic processes, has been to render internal state on state military conflict within Southeast Asia almost unthinkable.

In that, its achievement is at least as great as the EU’s. But its impact beyond Southeast Asia itself has ranged from slight to negligible. That’s not a criticism of ASEAN. But it naturally flows from its internal diversity, not least in relation to China.

Cambodia, Laos and, in a more complex fashion, Myanmar are Southeast Asian nations where China has enormous influence. Thailand and The Philippines are military allies of the US, although both Washington and Canberra lost a lot of influence in Bangkok when they foolishly boycotted the Thai government after a military coup.

Indonesia is dedicatedly non-aligned. It wants and needs Chinese money but it also has a big spate of arguments with Beijing. And it has a long history of spasmodic persecution of its ethnic Chinese minority.

Malaysia blows hot and cold on China. It wants China’s money and internal Islamic politics reinforce an inclination to put some distance between itself and Washington. Malaysia, too, has a history of some conflict between ethnic Malays and its Chinese minority and has laws that embody positive discrimination in favour of Malays against ethnic Chinese and Indians.

But Malaysia, with Singapore, is also a member of the Five Power Defence Arrangements with Australia, our only formal quasi-military alliance in Southeast Asia. Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei are majority Muslim nations.

Singapore is not a formal ally of the US but is strategically hard-headed and has taken strong action to keep the US militarily, economically and politically involved in Southeast Asia.

All the Southeast Asian nations, even the Chinese strategic clients, are more than a bit scared of China. They could well share Tony Abbott’s droll private joke that Australia’s view of China is driven by two contradictory emotions: fear and greed.

This Southeast Asian fear of China means they virtually all want the US to remain involved in the region.

The greatest weakness of the US in Southeast Asia is the lack of a trade and economic agenda, though it is a big source of both investment and aid.

But all the Southeast Asians recognise that Australia is a significant force helping to tie the US to the region. They also recognise that Canberra has more influence in Washington than any Southeast Asian nation does.

Therefore, they’re delighted if we take a stronger line against Chinese ultra-assertiveness in the South China Sea, its cyber attacks, its campaigns of political interference and all the rest.

Mostly, they don’t want to take such positions publicly themselves. Their own politics don’t work that way and they’re a bit worried about Chinese retaliation. We are wealthy, distant, protected by the US alliance and have a Western-style dialectical political culture, which means it’s expected that we take stronger positions.

No one in ASEAN wants us to try to be faux Southeast Asians ourselves. That doesn’t work. Lee Kuan Yew derided Gough Whitlam as “a sham white Afro-Asian”. We’re not ASEAN members, nor should we want membership. ASEAN has all kinds of rules, such as referring all disputes to an ASEAN Council, which nobody observes but that would tangle us up endlessly.

Foreign Minister Penny Wong seems to have made an analytical mistake in her approach to ASEAN. She tries to speak to ASEAN as though Australia were trying to be ASEAN, instead of being the closest possible friend, but nonetheless quite different.

Thus in a strange speech on Monday she framed the challenge to the region not as assertive Chinese behaviour that undermines the rules and norms of international conduct.

Rather, she framed the problem as “strategic competition” between the US and China, as though the two superpowers were equally to blame for this, or as though strategic competition were some kind of freak of nature, or approaching storm, in which we had no view as to right and wrong. This is analytically and politically misjudged.

The Albanese government has become publicly pusillanimous. It speaks of China now far more timidly than it did in its first months in office.

Enter ASIO director-general Mike Burgess. In a carefully worded and well-judged speech, Burgess described the actions of a foreign “A-team” of spies and diplomats targeting Australia. Everyone knew he meant China and this has been confirmed in numerous press reports. In authorised and clear public interventions in the past, Burgess has explicitly called out China, in relation to cyber theft.

Calls for Burgess to name an ex-politician, of which there are hundreds in Australia, he says was compromised by the A-team are completely misplaced. ASIO primarily collects intelligence, not legal evidence. Intelligence can be urgent but not fit for court. Burgess achieved his overriding communications objective, which was to warn of foreign, specifically Chinese, interference.

The Albanese government’s decision to put itself into public purdah over China is now dysfunctional. It shouldn’t be left primarily to agency heads to tell Australians about their strategic environment. No one in ASEAN wants us to become New Zealand which, despite its promising new government, has had no strategic input or consequence in Asia for the past 30 years.

In speeches and interventions by Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim and Philippine President Bongbong Marcos we see two contrasting, indeed contradictory, ASEAN approaches to China.