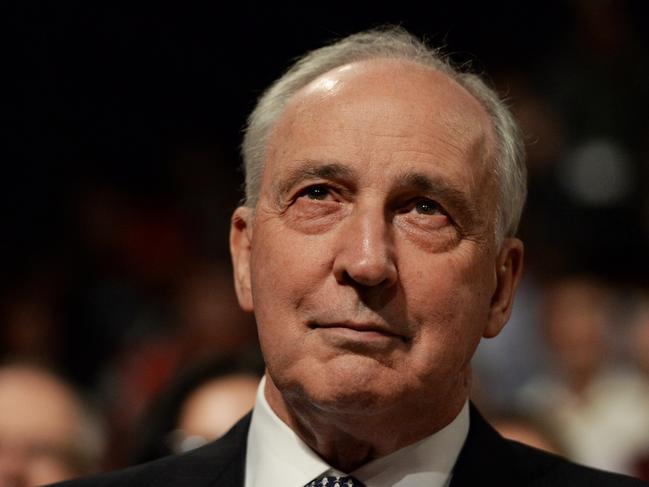

This is particularly the case with our current Treasurer, Jim Chalmers, who devoted several years of his life to writing a thesis about one of his role models, Paul Keating. It’s probably not a stretch to label Chalmers a fanboy of PJK.

But the difference between Chalmers and Keating, certainly as treasurers, is vast. Chalmers is effectively minding the shop, has no authority or persuasive powers in cabinet and is mainly hoping for the best. He is the antithesis of the reforming treasurer, notwithstanding his unconvincing efforts to establish otherwise.

Am I being too harsh here? After all, Chalmers took the time to write a lengthy essay about reinventing capitalism. Just recently, he gave a speech where he warned us about sluggish growth over the long term and the need for more investment lest living standards stagnate. He worries about the Australian economy being too fragile and subject to geopolitical risks. He wants to cultivate an anti-fragile economy.

There’s little doubt Chalmers has the gift of the gab; it’s just that his words (and messages) are both ill-conceived and unconvincing. He clearly thinks he needs to turn his back on neoliberalism, however that is defined. But in its place he has assembled a mishmash of thoughts, concepts and phrases to supposedly give coherence to his big-government spending agenda.

Chalmers leans on some unconvincing authors, such as Mariana Mazzucato, to support his arguments without realising she only finds favour with the far left of the political spectrum. But her premise that governments must act in partnership with companies to achieve certain predetermined, but often unachieved, outcomes is music to Chalmers’ ears. Others would simply call it crony capitalism.

Chalmers claims that boosting (directed) investment is the key economic challenge. It’s worth noting here that centrally planned economies such as the Soviet Union always had very high rates of (directed) investment, but this was never associated with widespread prosperity for its citizens.

The Treasurer nominates key areas for investment: the energy transition, technological change, advanced manufacturing, supply chains and critical minerals. He throws in the care economy – a misnomer for mainly uncapped government social spending – as well as greater competition policy and skills and training as the other elements in his agenda. Evidently, we are expected to believe all this amounts to a coherent approach to economic policy.

Chalmers has had more than his share of luck since assuming office. Commodity prices have stayed at historically high levels, which partly explain the budget surplus of $22bn achieved last financial year, and will contribute to another one this year. The tight labour market and the impact on income tax revenue, particularly via bracket creep, have also helped.

But the main point here is that Chalmers has utterly failed to rein in government spending. It is estimated that real government spending will rise from $627bn in 2022-23 to $775bn in 2026-27, an increase of nearly 25 per cent. As a proportion of GDP, government spending will be higher at the end of the forward estimates than in Chalmers’ first budget.

Let’s also not forget here the colossal amounts of money Chalmers has approved as off-budget spending items – think here national reconstruction, rewiring the nation, national housing. They add up to an additional amount of close to $50bn.

The contrast here with Keating as treasurer could not be more stark. For three financial years in a row in the late 1980s, Keating, in association with dogged finance minister Peter Walsh, achieved negative growth in real government spending. In 1986-87, government spending was 26.9 per cent of GDP; in 1989-90, it was 22.9 per cent. This was an amazing achievement but one Chalmers as Treasurer has no intention of emulating.

All successful treasurers effectively act as chair of an informal economic policy board comprised of the key ministers. There is not an area of government spending or regulation affecting the economy where the treasurer is not involved, be it industrial relations, energy, trade, federal relations, and the list goes on.

Sadly, for Chalmers, he is mainly an onlooker when it comes to the poor policies being foisted on the Australian people that will have very serious economic consequences down the track. The most obvious area is industrial relations where the relevant minister, Tony Burke, has imposed highly restrictive, pro-union changes with nary a thought for the impact on costs, productivity, investment or future economic growth.

Again, the comparison with Keating is brutal. Keating fully understood that the centralised setting of pay and conditions by a third party was incompatible with having an internationally competitive economy. He oversaw the dismantling of centralised compulsory arbitration and ushered in win-win enterprise bargaining.

Then there is the vexed issue of energy, where Chalmers has naively signed on to the jingoistic notion of Australia becoming a renewable energy superpower, a term with zero analytical content. Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen has imposed unrealistic timetables on various aspects of the energy transition while throwing around taxpayer money as if it were confetti.

The economic downsides of higher energy prices coupled with potential unreliability really don’t bear thinking about. A strong treasurer would have prevented this folly from gaining the momentum it has. Rather, Chalmers has bizarrely instructed the Productivity Commission to be guided by “getting to net zero and becoming a renewable energy superpower”.

A recent development of the federal government is to get into the game of using taxpayer money to pick winners, with a cool billion dollars heading out the door to establish a solar factory in the Hunter Valley. Either Chalmers has been too busy to read the news on these sorts of endeavours overseas or is simply wilfully ignoring the reality.

The developed world is littered with examples of failed experiments of governments handing out large subsidies to compete with Chinese solar manufacturers only for these projects to end in bankruptcy and lost taxpayer money. Think here Solyndra in the US, but there are multiple examples. Had Chalmers asked the PC for its advice, it’s pretty clear it would have told him to think again.

The bottom line is we have a very weak Treasurer in Jim Chalmers, who has constructed a flawed and misguided view of the role of governments in managing the economy. He shows no interest in the areas a reforming treasurer would normally spend most time on – tax and spending reform, deregulation and the like. He has also made a hash of the (dubious) restructuring of the Reserve Bank.

Rather than strip back unnecessary regulation, speed up project approvals across the board and allow businesses to make investment decisions on the basis of their assessments of future profitability, he wants to guide these investment decisions and to transfer dollops of taxpayer funds to achieve these guided decisions. It’s simply a highway to wasted money as well as even poorer productivity growth.

The vast majority of federal treasurers want to be reformers. They hope to be remembered as someone who saw problems in the economy and tried to fix them.