Referendum rules need reform before we vote on a voice

As Australia contemplates a referendum on an Indigenous voice to parliament, more attention needs to be paid to how that vote would be run. This is important because the current rules for holding a referendum are archaic and ill-suited to modern times. Fortunately, parliament has begun work on this through a new inquiry by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs.

The Constitution can be changed only by the Australian people at a referendum. This requires a yes vote from a majority of people eligible to vote in federal elections, as well as majority support in at least four of Australia’s six states. The Constitution is otherwise silent on how the poll is to be run, except to say that it “shall be taken in such manner as the parliament prescribes”.

This vests enormous power in parliament to determine the mechanics of the poll. It can decide whether voting is compulsory or voluntary, what information is provided to voters and the timing and regulation of the yes and no campaigns. These rules can be written to provide a fair contest, or to advantage one side over the other. As currently drafted, the rules tend to provide greater assistance to those opposing change.

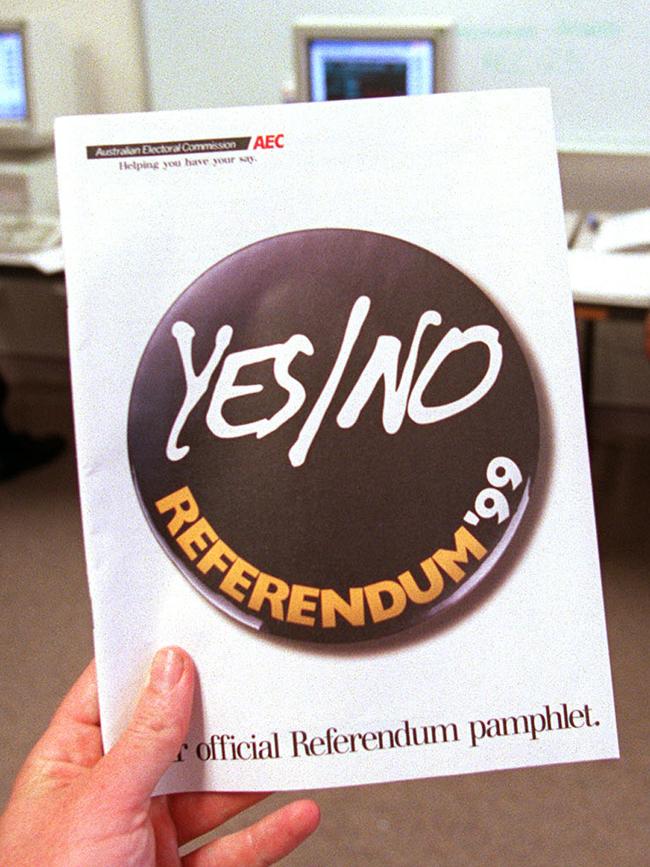

Parliament set down rules soon after Federation in 1901. They have been amended from time to time, including in 1912 to provide voters with a written pamphlet setting out 2000-word statements for each case. These must be approved by the parliamentarians who voted for and against the change. These rules persist today in the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act.

Decades have passed since these rules were substantially reformed to reflect changes in Australian society and new campaigning techniques. The result is a referendum rule book that is woefully inadequate. It shows its age in having key provisions that precede the introduction of radio in Australia, let alone television or the internet. As a result, the primary method for disseminating the yes and no case pamphlet is still for it to be printed and then posted to each voter. The rules also prohibit disorderly conduct at public meetings, but fail to account for the existence of social media.

Other rules have been shown over time to be problematic. For example, the commonwealth cannot spend money arguing for or against the change. There are merits to federal neutrality, but this makes little sense when there are no limits on any other organisation or government. As a result, past referendums have seen public debate monopolised by groups seeking to oppose reform. State governments have also used their finances to undertake blanket advertising against change, with no capacity for the commonwealth to respond.

These and other aspects of our referendum machinery legislation are long overdue for reform. Importantly, this needs to occur now before we embark on the next referendum campaign. Experience shows it is wise to do so well before the campaign itself. Without this, rational debate over what amounts to a sensible and fair process of holding a referendum risks being overtaken by political assessments of whether reform would favour the yes or no case.

This happened on the last occasion Australia came close to holding a referendum. In 2013, the federal parliament agreed to put a proposal to the people on whether to permit the commonwealth to make direct financial grants to local government. The idea won overwhelming support across the major parties. However, when parliament came to debate the rules for the poll, and in particular how much money should be provided to each side, agreement broke down. In the end, the proposal foundered and was never put to the people.

The House of Representatives standing committee should recommend a wide range of reforms to fix our referendum rules. An obvious place to start is to remove the restriction on commonwealth expenditure for or against a referendum. This could be replaced with a requirement that federal expenditure is divided equally between both sides, or in proportion to the number of votes cast for each case in parliament. Federal money could also be used to fund yes and no cases.

Another obvious place to start is the pamphlet. We can do better than providing each voter with 4000 words of printed material in their letterbox. At the very least, this information should be provided in a wider variety of formats and disseminated online.

The structure of the pamphlet also needs revisiting. The current design is about winning the argument at all costs and encourages exaggeration and misinformation. Partisanship and sharp disagreement are a necessary and important part of a referendum debate, but should not be the only information provided.

Voters should also be given neutral, explanatory material prepared by a referendum panel of independent experts and representatives of both sides. This would enable Australians to assess the competing positions in what can be a complex and confusing area. Without this, it is no surprise that voters have often rejected change on the basis of “Don’t Know? Vote No”.

George Williams is a Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Professor of Law at the University of New South Wales