Nor is Langton alone. Linda Burney has accused the “wantonly misleading” No campaign of using outright falsehoods as its “weapon of choice”. And just this week the Prime Minister slammed the “stuff that’s going into people’s Facebook posts” as “designed to spread misinformation”.

Now, to err is one thing; to lie quite another. The first is regrettable; the second is immoral.

In effect, the word “truth” comes from the Early and Middle English term for fidelity, loyalty, or reliability. Truthfulness is therefore the form of trustworthiness that relates to speech – and to deceive voters by knowingly telling untruths is plainly to breach that trust.

But the claims point to worse than moral opprobrium. To know “the truth” yet deny it, and intentionally induce others into error, is among history’s most sinister accusations – for it is precisely the Inquisition’s definition of heresy.

That too involved a change in meaning. Etymologically, “heresy” derives from the Greek term hairesis, which simply meant “choice”, typically of one opinion among others, and had no negative connotations.

By the time of Paul’s letter to Titus, heresy was viewed, far more pejoratively, as the fomenting of schisms among the faithful; however, the New Testament itself never enjoined silencing schismatics.

It was only in 385AD, some time after the emperor Constantine’s infamous decree against the “enemies of truth”, that Priscillian and four of his disciples were put to death for heresy, the first judicial execution of its kind. And it wasn’t until 1233, when Gregory IX established the Inquisition, that it became doctrine that heretics – “those who, having known the truth, perversely refuse to submit to it” – should “not just be separated from the church by excommunication, but shut off from the world by death”.

Winding that back took many centuries and countless horrors. The road to change is too long to recount; but nothing better highlights the transformation than John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689).

The fundamental disputes about the world we live in, Locke wrote, are matters of “judgment and opinion, not knowledge and certainty”, whose resolution could only be based on reason guided by “grounds of probability”. “Judgments and opinions” would inevitably differ; however, the differences were not to be feared – for civil strife’s root cause was not disagreement but the determination to “compel others to be of my mind, or censure and malign them if they be not”.

It is consequently no accident that Locke’s Essay Concerning Toleration, published anonymously in 1689, set the intellectual basis for religious freedom. Nor is it an accident that there was an inextricable connection between the development of religious toleration and the cementing of political liberty.

John Toland made that connection explicit in his path-breaking The state-anatomy of Great Britain (1717), which established the notion that to oppose the king, when one believed he was in error, was neither treason nor heresy, but the highest form of patriotism. So was born that seeming oxymoron, the concept of a “loyal opposition”, which, by jettisoning the Aristotelian view that “faction” (stasis) inevitably destroyed the polis, proved 18th-century Britain’s greatest contribution to democracy.

It was with all that in mind that Hannah Arendt, who no one could tar as a reactionary, launched her unforgiving and utterly unforgettable assault on those who claimed, in politics and public life, to have “the Truth”, God or even worse, “History”, on their side.

The reality, she wrote in 1958, is that social action, “with its innumerable, conflicting wills and intentions”, triggers changes whose outcomes “we are never able to foretell with certainty”. That contrasting evaluations will be made of the likely outcomes is consequently entirely natural; under those circumstances, to demand “mass unanimity” is nothing “but an expression of fanaticism”, which “by eliminating debate and diversity eliminates the very principles of political life”.

And by stifling controversy, the dogmatic claim to “the Truth” is the surest path to misery, “for the inexhaustible richness of human discourse is infinitely more significant” in securing social progress “than any ‘One Truth’ could ever be”.

In the end, said Arendt, it is only the capacity “to hold different opinions and be aware that other people think differently on the same issue (that) shields us from that god-like certainty which stops all discussion and reduces social relationships to those of an ant heap”.

But the accusations of lying do not just reek of the illiberalism that views critics as heretics, who merit being silenced by laws against misinformation and disinformation; they are also infused with rage.

The Yes campaigners’ rage can fairly be described as Homeric: like that of Agamemnon and Achilles, it is the fury of those who fume at not receiving the deference they believe they deserve. Like Shakespeare’s Coriolanus – in what is both the most Homeric and the most political of Shakespeare’s plays – they chafe at having to “beg of Hob and Dick their needless vouches”: that is, at having to win over the plebs by presenting a coherent case that rebuts, rather than merely vilifying, the other side.

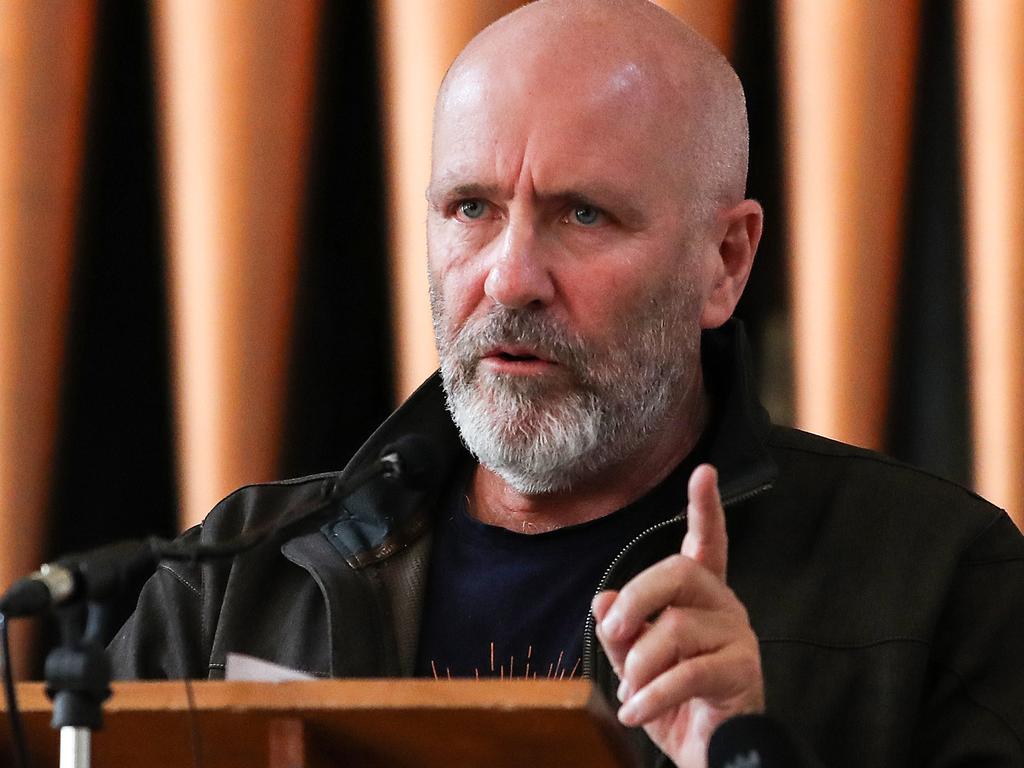

And like all Homeric rages, they veer from anger into contempt, epitomised by Noel Pearson’s tirades against Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, and sink into incivility.

Nor do the Yes camp’s intellectual leaders shy away from that fact: Megan Davis, for example, derides the calls for civility from what she terms “the civility brigade” as simply a cover-up for “marginalising already marginal groups” – a seemingly incongruous description of the lavishly funded and officially backed Yes campaign.

What Davis and others forget, however, is what the ancients well knew: that Homeric rage, with its trashing of civic coexistence, is an open invitation to Nemesis, the goddess of retribution against arrogance, who, by blinding the hubristic to reality, leads them into the humiliation of defeat and the agonies of doom.

Of course, viewed in contemporary perspective, that blood-soaked denouement seems better suited to the Homeric era than to our own. Fortunately, the modern world offers a milder, but no less devastating, cure to the pretensions of all those who rage at their critics – a cure, worth quoting in full, that Alice, travelling through Wonderland, spells out when she refuses to answer the Queen of Heart’s ridiculous questions.

“ ‘How should I know?’ said Alice, surprised at her own courage. ‘It’s no business of mine.’ The Queen turned crimson with fury, and, after glaring at her for a moment like a wild beast, began screaming ‘Off with her head! Off with …’. ‘Nonsense!’ said Alice, very loudly and decidedly – and the Queen was silent.”

With outraged cries of “off with their heads!” bellowing across Australia, who could possibly put it better?

According to Marcia Langton, “the public square has been flooded with egregious lies about the referendum proposal”.