Yes, yes, Aaron Sorkin’s TV series is fictional. But when it first aired in 1999 there was a sense that some of what Jed, Leo, Josh, Toby, Sam and CJ did, or tried to do, could be done, or tried, in the real world. Their fictional attempts at sound policy might be replicated, to some degree, in real life. As flawed and vexing as Sorkin’s characters were at times, their inspirational politics unfolded with America on a winning streak. A decade before the first season, the Berlin Wall had fallen and the West had won the Cold War; Nelson Mandela was released from prison, ending apartheid soon after. Capitalism was spreading, third-way politics was blossoming. New technology was still exciting – Twitter wasn’t yet a thing. A peace had been secured in Northern Ireland. The US was the sole superpower. The West was on the up, not by the barrel of a gun but by the triumph of ideas about freedom over oppression.

True, on the other side of the ledger, wars broke up Yugoslavia, civil wars and genocide blighted the African continent, a recession hit Australia and the dotcom bubble burst. Then, by season three, 9/11 had changed the world.

Still, The West Wing reflected a time when more of us believed at least some of our leaders had convictions, could effect real change, and bipartisanship happened for important reforms.

This was the era, for example, when John Howard supported the Hawke-Keating economic reforms.

When was such bipartisanship reciprocated? A decade later, an American version of House of Cards was made, capturing a darker time. While the original and far superior British version appeared in 1990, that too reflected a pessimism in British politics after Margaret Thatcher overstayed her welcome. Machiavellian politics is nothing new.

That said, House of Cards returned to our screens for a reason, with the sinister Frank and Claire Underwood followed by that other big, bleak hit, Succession, a series about powerful, greedy, nasty people who can barely speak in full sentences. A Succession drinking game for use of the C-word would lead to a dose of alcohol poisoning requiring a hospital admission.

The show reflects the stomach-churning worst about our current age, its stunted, expletive-laden, polarising language a euphemism for the Twitter cesspit.

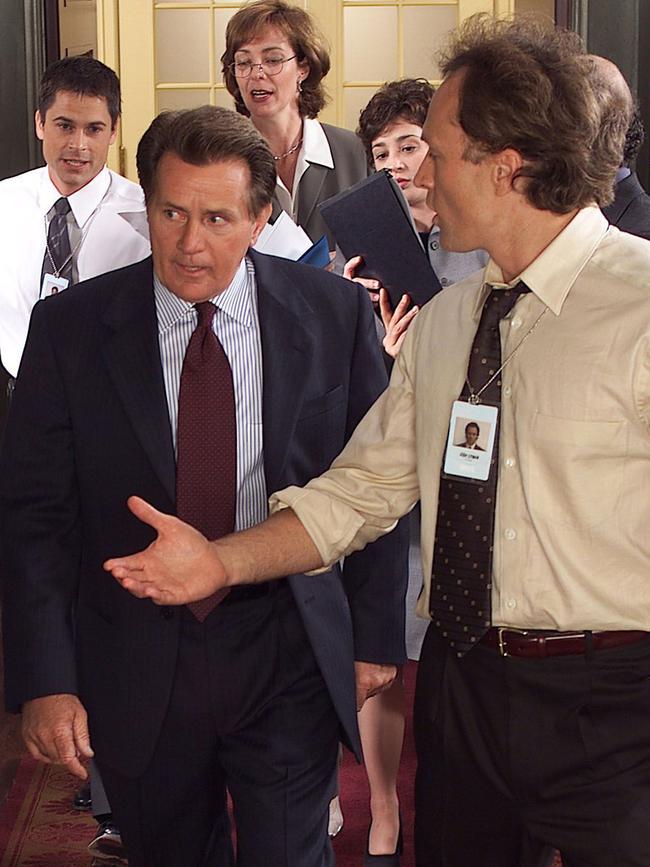

We talk about this often in my home, how The West Wing remains unmatchable, with its pre-2000s level of optimism, humour and clever, classy writing that moves seamlessly between a sex scandal where Sam (Rob Lowe) “trips” on to a prostitute to the president quoting, in context, Cicero and the Bible. In this show, Republicans can get on board with Democrats.

There is a scene that captured the show and the time, when speaking to his loyal – yes loyal – staff, the fictional Democrat US president says: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world. Do you know why?” A young speech writer answers: “Because it’s the only thing that ever has.”

Who among us doesn’t yearn for a politician who will believe what Sam does: “Education is the silver bullet. Education is everything. We don’t need little changes. We need gigantic revolutionary changes. Schools should be palaces. Competition for the best teachers should be fierce. They should be getting six-figure salaries. Schools should be incredibly expensive for government and absolutely free of charge for its citizens, just like national defence.”

Sure, the caveat from the staffer is: “That is my position. I just haven’t figured out how to do it yet.” We never hear such sentiments from any politician, let alone a conviction to get there.

My children, all in their 20s, lament that if this show were remade it would be too far-fetched or a spoof. Cynicism sets in, stays around, grows worse for a reason.

Since the awakening of political consciousness in my kids, in the mid-noughties, no leader has impressed them with a set of convictions: Howard was in his last term in office, then came Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard, Rudd again, Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull, Scott Morrison and Anthony Albanese. No treasurer since Peter Costello has embarked on serious structural change. His successors have been tinkers and fiddlers.

Many other under-30s may agree that recent leaders have done little good, other than campaign to stay in power. The thought of a modern politician achieving big things to improve people’s lives has become outlandish.

By contrast, for many years, at the same or similar age, I loved election day. We had leaders like Bob Hawke, Paul Keating, Howard. Love them or loathe them, these men had a clear set of beliefs. Each raised the pulse of the country, rather than putting us to sleep.

Thatcher did the same in Britain, inspiring new generations of politicians who loved her and wanted to perpetuate her views or hated her and opposed her views with an equal passion. Tony Blair made his mark carving out the so-called third way for a modern Labour Party. In the US, Ronald Reagan spoke about government and the economy in a way that others had not.

Though flawed, too, these leaders stand as giants in contrast to the longer list of pygmy political leaders who came after them, whose names and periods in office are greeted, especially among the young, with a yawn.

Would younger voters get excited about a new Hawke, Keating or Howard? Probably not. As Centre for Independent Studies executive director Tom Switzer has written, young Australians born from 1981 onwards “have genuine anxieties … they feel the economy is rigged against them”. They live in a debt-ridden society, have experienced no real wage growth, home ownership is out of reach for many – because governments, left and right, have pursued policies that have failed them.

And, as the annual Lowy Institute poll shows, their cynicism translates into young people being more ambivalent than older Australians about the value of democracy.

The mediocrity of our politicians remains a problem for our democracy. How can it not? Take the current Prime Minister. For a bloke who talks a lot about his public housing upbringing, his focus on the voice over the genuine anxieties and cost-of-living issues for millions of Australians, young and old, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, is surprising.

The most telling part of this week’s Newspoll is the most pronounced dip in support for this proposed change to our Constitution is among women and younger voters. It was accepted wisdom, after all, that bursts of emotion and slogans would seduce young voters. Instead there is growing and understandable doubt about the proposal among them, too.

Cynicism about politics is not, by any means, unhealthy. Nor should cynicism be a permanent state of affairs. This country has had political giants in the past who have transformed the country according to their convictions. That can happen again, but only if there are new entrants who believe in something more than adulation and power.

As Toby says in The West Wing, “It’s not the battles we lose that bother me, it’s the ones we don’t suit up for.” In the meantime, many of us will lug ourselves to the ballot box to avoid a fine, and watch re-runs of The West Wing.

You could not make The West Wing today. The show that hit television screens 24 years ago last week is a product of its time. Just as The Norman Gunston Show reflected a period of humour that is far too offensive for our 21st-century sensibilities, the sparkling optimism of The West Wing doesn’t suit our cynical times. More’s the pity.