Political class can’t be blamed for follies of big business

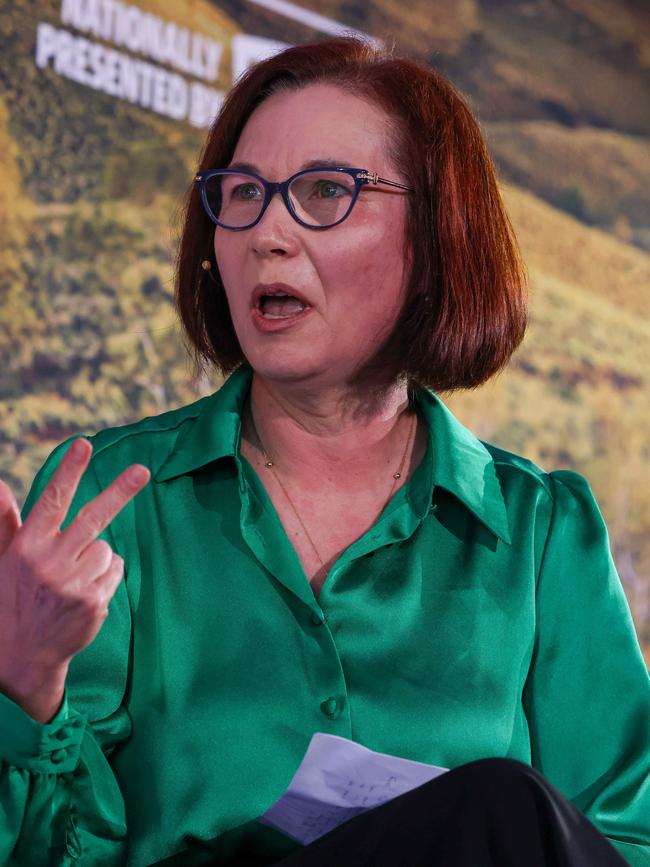

At the Business Council of Australia’s annual dinner on Tuesday, its chief executive Bran Black frankly told Anthony Albanese, who was in attendance, that the country was “losing its way” under his government. For good measure, he criticised Peter Dutton’s supermarket divestiture proposal.

A week earlier, Minerals Council of Australia boss Tania Constable accused the Prime Minister of bringing “conflict to every workplace” with his industrial relations laws. And let’s not forget Commonwealth Bank CEO Matt Comyn’s outburst at the House Economics Committee, where he accused the bank’s political critics of engaging in “fact-free rhetoric” and “insidious populism”.

It is easy to see why our corporate leaders are frustrated. They are politically friendless. As Oscar Wilde might have observed: alienating one side of politics might be seen as misfortune; alienating both sides smacks of carelessness. Our corporate titans like to blame others for their predicament, but they have been reluctant to look in the mirror. I would argue that, with only a few honourable exceptions, they are entirely responsible for their lack of political influence.

We have seen this movie before. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, large companies in the US, Australia and other Western countries found themselves in a similar predicament. Against the background of high inflation, rising environmental activism and a growing distrust of major institutions, they were criticised for putting profits before ethics, focusing too much on their shareholders and not enough on their (vaguely defined) stakeholders. Rather than reject this line of argument, the corporate community capitulated to it, giving birth to the notion of corporate social responsibility.

While many economists at that time – no doubt reflecting their left-leaning politics – welcomed the advent of CSR, the eminent economist Milton Friedman immediately saw through it. In a blistering 1970 op-ed for The New York Times, which could easily have been written today – Friedman argued that corporate executives are, and should be seen as, “employees” of their shareholders.

Their sole responsibility, therefore, was to “conduct the business in accordance with their (shareholders’) desires”. In other words, to obtain the highest possible returns for them, consistent with the laws and customs of the land. As Friedman put it, when executives trade profits off against other objectives – whether it be adopting environmental measures (beyond what is legally required), hiring unqualified staff (to achieve minority hiring targets) or even volunteering to forgo justified price increases – they were effectively imposing a tax on the business’s owners.

If they short-changed their employees and customers in the same way – that is, pursued social agendas that lowered wages or raised prices – they were similarly taxing them. Friedman said in doing so, the executives were arrogating to themselves a core function of government – raising taxes to fund desired social initiatives – but without the critical constitutional and political guarantees, including fair elections and laws passed by parliaments, that give “real” government action legitimacy.

They were guilty of “taxation without representation”, which as we know excites the passions of those not represented. By politicising the commercial world in this way, these executives, Friedman argued, implicitly accepted “the socialist view that political mechanisms, not market mechanisms”, should allocate “scarce resources to alternative uses”.

Friedman’s insights help shed light on why the corporate community has alienated both the left and the right in today’s Australia. By embracing CSR in all its forms, it has not appeased the left, but rather emboldened it to make increasingly ambitious attacks on private enterprise. Today, a super profits tax proposed by the Greens. Tomorrow? Perhaps direct regulation of key prices by a minority Labor-Greens government.

And CSR has understandably outraged many on the right. When our big banks refuse to lend to perfectly legal fossil fuel-producing businesses, they are not only forgoing profits but, as Friedman pointed out, acting as an illegitimate shadow government.

And let’s not forget the voice referendum and Woolworths’ Australia Day boycott, when corporate executives effectively did the same thing. (You might ask why shareholders do not discipline executives who fail to act in their financial interests? In Australia, the big industry superfunds are major cheerleaders for CSR, urging senior executives to do more, not less.)

To object to corporate social activism is not populism, as some business leaders condescendingly claim, but a reflection of the traditional view that the commercial and political realms should remain separate. If our corporate leaders are to rebuild their influence, they must go over the heads of our politicians and appeal instead to the hearts and minds of the public. They should have the courage and intelligence to make an ethical case for private enterprise.

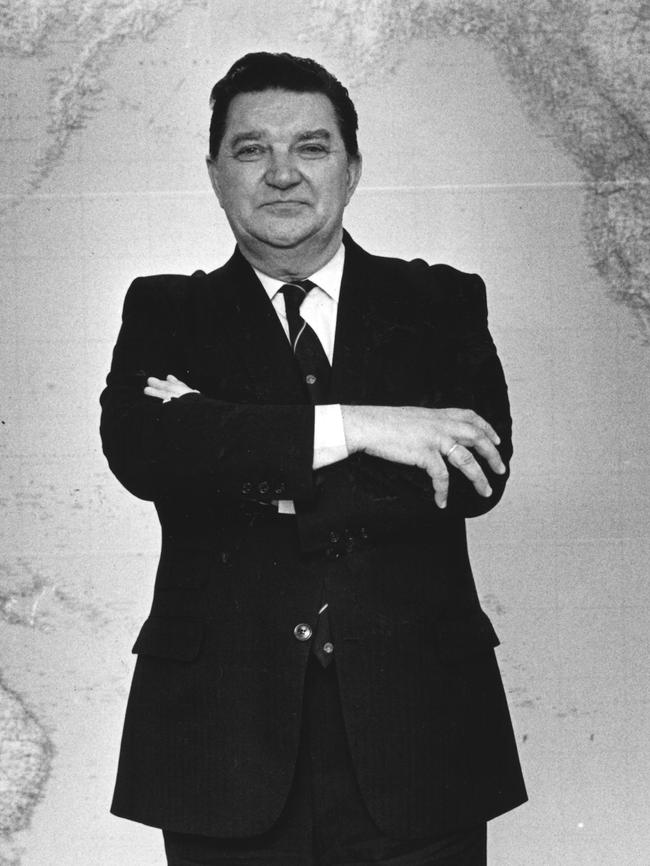

The BCA’s first president, Sir Arvi Parbo (an immigrant made good who also chaired BHP), knew this, committing the organisation at its founding to uphold “the principles of free enterprise”.

As Joseph Schumpeter pointed out in 1943, two such principles stand above all others: the fundamental human right to do as we please with our own property, whether it be our human capital or our life savings; and, as a corollary of this, a belief in the inherent moral superiority of an economy based on freedom of contract rather than collective coercion.

Of course, the Albanese government’s retrograde industrial relations changes represent a frontal assault on each of these values, as literally millions of contractors, gig economy workers and casual employees are painfully finding out.

Rather than threaten to cut back on hiring or investment, our corporate leaders should be standing up for the rights of these people; and, while they’re at it, remind everyone of the moral – not just the economic – superiority of capitalism over every possible alternative. Now that would be a show of real corporate social responsibility.

David Pearl is a former Treasury assistant secretary.

It appears the worm may be turning. Putting aside their usual timidity and reluctance to say boo to our political leaders, Australia’s corporate leaders seem to have had enough.