PM’s precarious US-China juggling is about to reach its use by date

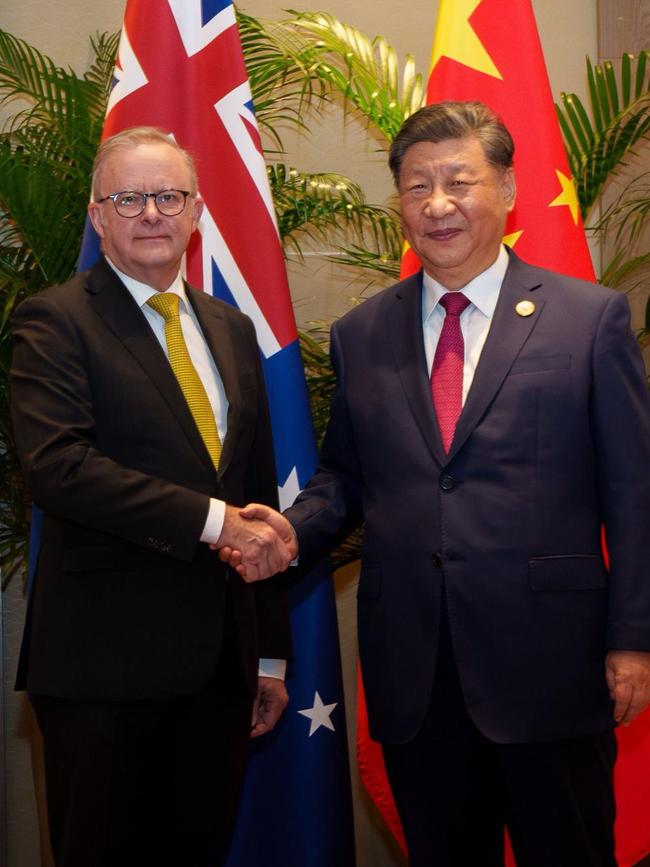

The two leaders met for 30 minutes on the margins of the G-20 summit. The Prime Minister would have had at best 15 minutes to make his points. Xi has passable English-language comprehension but uses translation. This means Albanese had seven or eight minutes speaking time – about as long as it takes to hard-boil an egg.

Albanese told a post-meeting press conference that he discussed “opportunities for greater practical co-operation, such as the renewable energy transition and climate change”.

Albanese then said he raised: “Australia’s views on issues affecting regional and international peace, stability and prosperity, ranging a number of bilateral points as well, including consular matters.” But wait, there’s more: “I raised the issues of human rights. I raised Taiwan. I raised cyber. I raised the supply of assets to Russia. I raised the ICBM missile test that I previously raised as well with the Chinese Premier.”

Then there were talks on trade, Australia’s alliance with the US – Albanese says he wants more “middle to middle communication between China and the United States” – and on the PM’s next visit to Beijing.

The only issue Albanese was adamant he didn’t raise was Donald Trump – a pity because China’s focus was all about trying to put a wedge between Washington and its G-20 partners, nine of which are treaty military allies.

It would be impossible to deal with all the issues Albanese says he raised. A journalist described these G-20 side-meetings as political speed dating. Not so. Speed dating (I’m told) offers the possibility of hope, of discovery. That is the opposite of the pre-scripted, deadening encounters Xi demands.

Albanese wants to create the impression that he will, to quote his favourite phrase, “disagree where we must” with China, but this belies his overall deference to Xi. His opening statement at the meeting – delivered to camera – looked only to an “auspicious” meeting, “encouraging progress in the stabilisation of our relationship” and building a “deeper understanding” with Xi.

No one on the Chinese side, no officials of either country and none of the media reporting these meetings would’ve believed there is much truth in these fond aspirations. Build a “deeper understanding”? Our intelligence community understands precisely why China is aggressively building its military power – the plan is for domination, not like-minded teamwork.

A “stabilised” relationship? Only if you think that selling lobster is the height of Australian strategy. The point about an abusive relationship is to get out of it, not pursue more harm.

The tragedy of Australia’s China relationship is that Albanese has forgone substance in favour of the pretence of co-operation. China’s communist rulers could not be more delighted. This is why before Albanese’s meeting with Xi the “party/state” newspaper, the China Daily, praised Labor for displaying “strategic autonomy”, offering a “useful reference” for other countries to follow. The approved behaviours include “shelving differences”, “seeking common ground” and avoiding “exclusive cliques, bloc politics, or camp confrontation” – all code for alliance relations.

But as Albanese told the media: “Our security partnership, our alliance, is with the United States.” True enough. Australia is not strategically autonomous. Successive governments have refused to pay the defence costs that might deliver more credible self-reliance. Beijing doesn’t harbour any expectation that Australia will distance itself from the US, but Xi will settle for behaviour that puts grit in the gears of alliance co-operation.

Based on their public criticisms, what particularly annoys China is AUKUS, Australia’s increasingly close trilateral defence co-operation with Japan and the US, and the Quad, which brings in India.

The challenge for Albanese is not to imperil the longer-term benefits of AUKUS and alliance co-operation while trying to sustain “stabilised” relations with China. These aims aren’t compatible. That means a core Labor policy objective may not survive for long during the life of a Trump administration pushing a tougher China agenda.

A core aim of the Albanese government on this side of a federal election must be to avoid a clash between the incompatible hopes of its China and US alliance policies.

This explains Albanese’s bizarre lack of interest in meeting Trump. The PM was happy to avoid several question times in parliament to attend one of the most pointless G-20 meetings ever, but could not find the motivation to visit president-elect Trump a few-hour’s flight away in Florida. Albanese should’ve gone to make the case for speeding up AUKUS, to discuss how he would put more substance into Australia’s defence, and how to better support the growing US military presence in northern Australia.

None of these objectives is consistent with Beijing’s model of Canberra’s “strategic autonomy”. Ironically, all these steps would make us more consequential in Chinese thinking.

My guess is that Albanese will work hard to set the date for another visit to Beijing, and his first meeting with Trump, to well after the federal election. That delays the reckoning between an underperforming defence and alliance strategy with the fake news of a “stabilised” China relationship.

Silly talking points won’t paper over this fundamental policy disconnect for much longer.

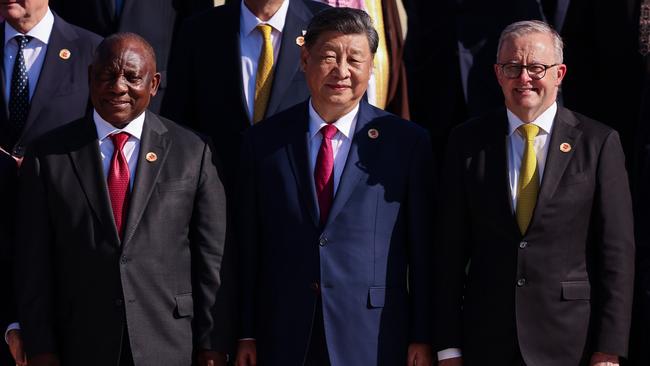

Anthony Albanese described his dialogue with Xi Jinping in Brazil last Monday as “crucial” and his personal engagement with the Chinese leader as steering a “patient, calibrated and deliberate approach (that) created many thousands of new jobs in Australia”