Let’s face it, hardly a day passes when there isn’t a story about a stressed family or individual unable to find affordable rental accommodation. Reliable tenants are turfed out of their rented house; renters make several applications, only to be knocked back each time; rents are increasing at alarming rates and gobbling up higher proportions of net incomes.

Given that affordable and safe shelter is one of our most basic needs, the rental crisis is an issue that should concern all levels of government. Let’s not forget here that around one-third of the population are renters and even though the proportion of the population who are homeowners appears to have levelled out in recent years, the absolute number of renters has risen quite sharply. When it comes to dealing with the rental crisis there is a great deal of woolly thinking, and initiatives are put forward (and sometimes implemented) that make matters worse.

There really is only one word you need to focus on when it comes to the policy challenge of ensuring adequate rental accommodation: supply.

Before we get to the core solutions, it’s worth painting a picture of rental accommodation in Australia. There are actually some differences across the states and territories; there are also some differences from other countries.

The vast majority of rental accommodation is provided by the private sector, with public housing accounting for a small proportion (around 4 to 5 per cent). There is relatively more public housing in South Australia and the ACT. Until recently, public housing has been declining proportionately as old stock is demolished and new building programs have been slow to get going.

The type of rental accommodation varies from stand-alone houses to apartments. There is some boarding house accommodation, but a lot of this is substandard. The proliferation of high-rise apartment buildings in several cities has led to higher proportions of renters living in apartments than was once the case.

In terms of who owns these rental properties, it’s very much a mum-and-dad affair in Australia, with 70 per cent of owners of rental housing owning just one investment property. Less than 2 per cent of investors have five or more properties. (Several parliamentarians own multiple investment properties.)

There is very little corporate ownership of long-term rental accommodation in Australia, which contrasts with several other countries. While there is a lot of discussion about a build-to-rent model, there are numerous impediments to the involvement of property trusts and superannuation funds, particularly related to tax. The fact is that the returns on investment in residential rental accommodation have been too low to attract large-scale investment.

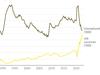

In the meantime, there is a stereotype of the avaricious owner with multiple properties making huge claims against the taxpayer via negative gearing. This is highly misleading. In point of fact, the fiscal costs of negative gearing have fallen significantly – at least until recently – in line with falling interest rates.

According to the latest figures (2019-20), the cost of negative gearing to the budget was only $166.5m compared with more than $9bn in 2007-08.

Indeed, one of the factors explaining the rental crisis is the relative absence of investors in the residential real estate market.

Following on from the direction of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority in 2016, loans to investors were rationed and by 2020 investors were selling more homes than they were buying. In addition, some owners of rental properties were switching from long-term rental arrangements to Airbnb. It’s not clear that the overall impact of the switch has affected long-term rental supply or prices significantly, but in particular markets it clearly has had an impact.

Some state governments also have decided to introduce legislative measures intended to give tenants a better deal on ending of leases, permission for pets and other measures. For the owners of properties, these laws have made their investments less attractive and potentially discourage new investment. Changes to land tax also have eroded the value of investment properties, with the recent proposed Queensland law (to include interstate properties in the determination of the rate to be levied) potentially driving down the returns for investors.

Unsurprisingly, governments have shown concern for the predicament facing so many renters.

One common response has been to support first-home buyers to enable renters to escape the rental treadmill. Examples include first-home buyer grants, exemptions of discounts on stamp duty and access to concessionary finance. Almost all of these increase the price of housing by acting on the demand side. There is also an incorrect assumption that most renters in distress are just one step away from home ownership. The reality is many renters are not close to home ownership nor is it on their radar.

Two new terms have entered the discussion: social housing and affordable homes. Social housing is just another term for public housing – in part to gloss over the many problems known to be associated with public housing.

All state governments have ambitious plans to fund the building of additional social housing but, given the waiting lists, the new accommodation will be filled quickly. With the low turnover of existing tenants, there will be a need for more supply.

Affordable housing refers to below-market rental accommodation for frontline workers close to places of work. Judged by the shambles of a previous attempt to establish such housing under Labor’s National Rental Affordability Scheme, it should not be assumed new initiatives will succeed.

Notwithstanding, the federal government is proposing to a $10bn Housing Australia Future Fund to build 30,000 new social and affordable housing properties across five years. This is a drop in the ocean and encroaches into a space that is the role of states.

The only real solution to the rental crisis is more rental properties. This solution is even more important given the federal government’s determination to drive up the number of migrant arrivals. Getting the corporate/superannuation sector involved would be helpful, but this is unlikely to deliver short-term gains given the impediments that need to be removed.

State governments should realise that putting their feet on the accelerator and the brake at the same time doesn’t work – they need to make it unambiguously more attractive for private investment in the rental market to relieve the extreme pressures we see and the hardship for families and individuals this entails.

It’s a reasonable question to pose: should we have had a summit on the rental crisis rather than a summit on jobs and training? After all, we are very close to full employment and most of the suggestions from that talkfest had already been decided or were unhelpful – multi-employer bargaining being an obvious example.