Listen to Noel Pearson, Marcia Langton on indigenous recognition

My passion for reconciliation was aroused many years ago when I first appreciated that indigenous Australians were not only the most profoundly disadvantaged group in Australian society but the most discriminated against.

Learning of the courageous exploits of Yorta Yorta ancestor Uncle William Cooper added to the intensity of my feelings: in 1938, in a galvanising moment of defiance and solidarity, he led a deputation from the Australian Aborigines League to the German consulate in Melbourne to protest against the Nazis’ persecution of the Jews. The delegation was refused admittance, but that didn’t stop Cooper. He spent his whole life struggling for justice for his people, and for the oppressed more generally.

Inspired by Cooper and many indigenous leaders like him through the ages, we must never lose our passion for reconciliation.

And let’s not become dispirited about the recent emergence of divergent views on the issue of indigenous constitutional recognition. It’s certainly not too late to embrace new approaches. Any suggestion to the contrary is complete nonsense. What is important is taking the time to get it right.

We still have that time.

The Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians, which I was privileged to co-chair alongside my wise friend Patrick Dodson, the father of reconciliation, focused on the importance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ free, prior and informed consent. One of the four principles adopted by the panel to guide our proposals was that they must be of benefit to, and accord with, the wishes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as well as capable of being supported by the overwhelming majority of Australians.

The panel considered, but set aside, the need to satisfy any particular political agenda, opting instead to produce a final report that, in effect, assumed cross-party political support, without which no referendum can reasonably be expected to pass.

The indigenous members of the panel caucused separately, with full consent of the whole panel because we each understood that our recommendations must be acceptable to indigenous communities across the country.

In a sense, our approach was a microcosm of what now must occur at a national level.

A key recommendation of the panel’s report focused on the importance of indigenous consultation. It reads: “If the government decides to put to referendum a proposal for constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples other than the proposals recommended by the panel, it should consult further with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their representative organisations to ascertain their views in relation to any such alternative proposal.”

My good friend Noel Pearson’s recent contribution on this issue — a proposal to establish a new indigenous body to give indigenous people a formal parliamentary voice in the laws and policies made about them, and to keep the practical inside the Constitution and the symbolic outside of it — is not in conflict with such a recommendation.

If ultimately passed at a referendum, Pearson’s indigenous body proposal would represent a huge step forward.

It may well have greater implications for indigenous empowerment than a blanket prohibition on racial discrimination.

Australia is fortunate to have the benefit of Pearson’s intelligent and forthright focus here.

I value his views very highly and feel certain that, had they emerged earlier, they would have been incorporated into the panel’s recommendations.

But right now, what I think is really not that important. Rather, what is important are the panel’s recommendations, including the need for further consultation to take place with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples about any new proposals that have emerged, including Pearson’s.

It is certainly not too late for this to occur. Getting it right is so much more important.

This is completely consistent with the spirit of the expert panel report.

Even so, we should also not lose sight of the fact the recommendations in the report were unanimous and they followed very extensive consultations. Not only that; we anticipated there might well be variations on these recommendations, particularly after input from conservative sections of society. That has proved to be so.

I strongly urge time and space now be given to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to debate their different views.

As Patricia Karvelas and other commentators have rightly pointed out, “the truth is that without the support of indigenous Australians, the referendum is dead”.

This view highlights the importance of indigenous Australians working together to build a consensus on the foundational principles before the model is settled.

Marcia Langton, who co-chairs the Cape York Partnership, has said she sees Pearson’s proposals as a means of uniting Australians across the political spectrum and giving the referendum a better chance of succeeding.

She also makes the point that, by contrast, a constitutional clause prohibiting racial discrimination may result in even more hard-fought, contested litigation for indigenous Australians, which would be disastrous for the national fabric.

In truth, as a nation, we’ve only just recovered from the bloody native title wars that, a decade or so ago, were waged through the courts. The prospect of more of that to come is daunting, indeed.

But as I have said, my views are beside the point. What is important are the insightful views of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders such as Dodson, Pearson, Langton, Galarrwuy Yunupingu, and many others across the country.

Relevantly, there seems to be a growing concern among some leaders that the panel’s recommendations undermine the prospects of achieving broader justice for indigenous Australians in the future, through a treaty or the like.

To the contrary, as law professor George Williams has said, proper and just constitutional recognition could actually provide a foundation for those prospects to be accommodated in the future.

There has recently been a call for Tony Abbott and Bill Shorten to meet indigenous leaders. I certainly support such a meeting taking place, if the purpose is to provide an opportunity for our political leaders to reiterate their dedication to indigenous constitutional recognition and to discuss how this can best be achieved.

However, if the purpose of such a meeting is to focus on the precise words to be used in specific proposed amendments to the Constitution, I believe it would be premature.

Before such a meeting takes place there clearly needs to be a meeting of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders, who together represent vast and disparate constituencies, to discuss and debate the issues of importance to them. The National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples is holding such a meeting next month. The outcome of that gathering, and other meetings, will be crucial to the success of any referendum.

So let’s not panic. And let’s not foreclose on emerging differences of opinion. The scene is now set for mature and informed discussion to occur.

If we are to get this right, we must be patient, and remain passionate. As Pearson reminds us, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have been waiting a very long time already.

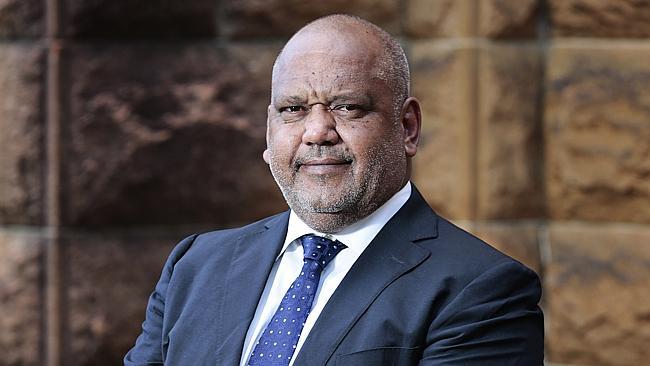

Mark Leibler is the senior partner at Arnold Bloch Leibler and was co-chairman of the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians.