How the Coastwatchers turned the tide of the Pacific War

The Australian Coastwatchers brought the tide of Japanese invasive successes to a shuddering halt, when two watchmen spotted and reported an impending invasion fleet of 5,500 Japanese troops. The Coastwatchers’ observation was pivotal as it precipitated the Battle of the Coral Sea of May 1942, and stopped the invasion of Port Moresby. United States Admiral, William F. (Bull) Halsey would later state that “the Coastwatchers saved Guadacanal, and Guadacanal saved the South Pacific”.

In early 1941, ten months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Australian government set up the unpublished “Malay Barrier” and deployed a series of “Bird” defence forces on the islands north of Australia - the Sparrow Force on Timor, Gull Force on Ambon and Lark Force at Rabaul.

Tragically, these undermanned and under-equipped forces were totally outnumbered by the superior Japanese invasion forces that swept south after Pearl Harbor, incurring huge losses for Australian troops.

The first of these invasions occurred on January 22, 1942 just six weeks after Pearl Harbor, when the Japanese invaded and occupied Rabaul, killing and capturing 73 per-cent of the token Australian force left to defend it. 1,053 of these POWs became casualties in Australia’s largest maritime disaster of the war, when an unmarked prison ship named Montevideo Maru was sunk by a US submarine.

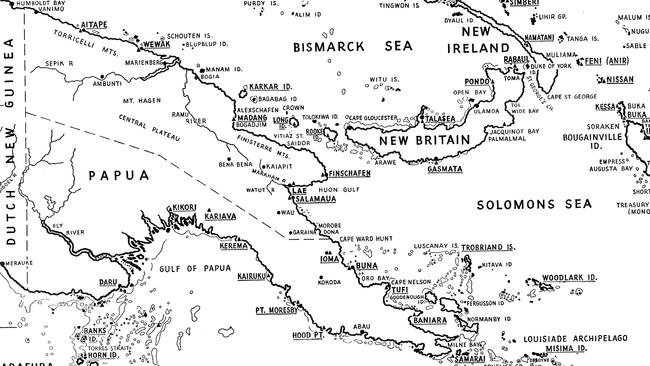

The founder and commander of the Coastwatchers, Eric Feldt explains in his historic book, The Coast Watchers, that in late February 1942, after occupying Rabaul, “the Japanese despatched a force to occupy Lae and Salamaua… Buka Passage and the Shortland Islands…. Then, in May, they essayed to take Port Moresby from the sea, at the same time occupying Tulagi”.

Japan’s ongoing effort to strengthen the offensive positioning of their empire in the South Pacific meant that Port Moresby was a primary target.

According to James P. Duffy in his book War at the end of the World, Port Moresby was Japan’s strategic goal. The MO Carrier Striking Force, as it was codenamed by the Japanese, intended to isolate Australia and New Zealand from their ally, the United States, in preparation for the Japanese attack on Australia.

However, fortuitously, “an Australian Coastwatcher on the Solomon island of Bougainville provided the first news of Japanese movements when he sent his message on 2 May 1942, that a large force of enemy ships was sailing south towards Tulagi. A second, similar despatch was made later the same day by another Coastwatcher on New Georgia. Both Coastwatchers transmitted their sightings to headquarters at Port Moresby, which relayed the message.”

Two days later, the Coastwatchers’ warnings enabled the Allied forces to meet and vanquish the invasion fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy in the Battle of the Coral Sea, which was fought from May 4-8, 1942. This was the first naval repulse of the Japanese following their series of conquests, as they moved from the northern to the southern hemisphere. As Duffy records “the most important result of this historic battle was that it averted the invasion of Port Moresby, with all it portended for the safety of Australia and the future of the war”. Moreover, he notes, “never again would an enemy fleet attempt to invade that vital port city”.

After Japan’s defeat in the Battle of the Coral Sea, their battered and bruised invasion forces limped back to Rabaul, thus saving Port Moresby from the ‘walk-in, capture and occupy’ fate, which had been suffered at Rabaul, Timor and Ambon.

Immediately following the Coral Sea battle, Japan and the United States fought a six-month long battle of attrition for control of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, during which time the Americans came perilously close to defeat. Such a defeat would have been catastrophic for Australia. Fortunately, the Australian Coastwatchers played a vital role in a key victory: the ultimate American success at Guadalcanal.

Coastwatchers regularly sent two-hour warnings of bombers with supporting fighter squadrons. Such messages would be sent from their campsites in the enemy-held jungles of New Britain, New Ireland and Bougainville, to the US authorities on Guadalcanal, and the Australians at Port Moresby. These alerts saved countless lives, with planes ‘up in the sun’ ready to pounce, the Navy’s battleships on ‘battle stations’ and their land forces with their anti-aircraft weaponry ready and waiting for the Japanese attacks.

These warnings also enabled the US forces at Guadacanal to defend hard-won territory, which were of enormous strategic value.

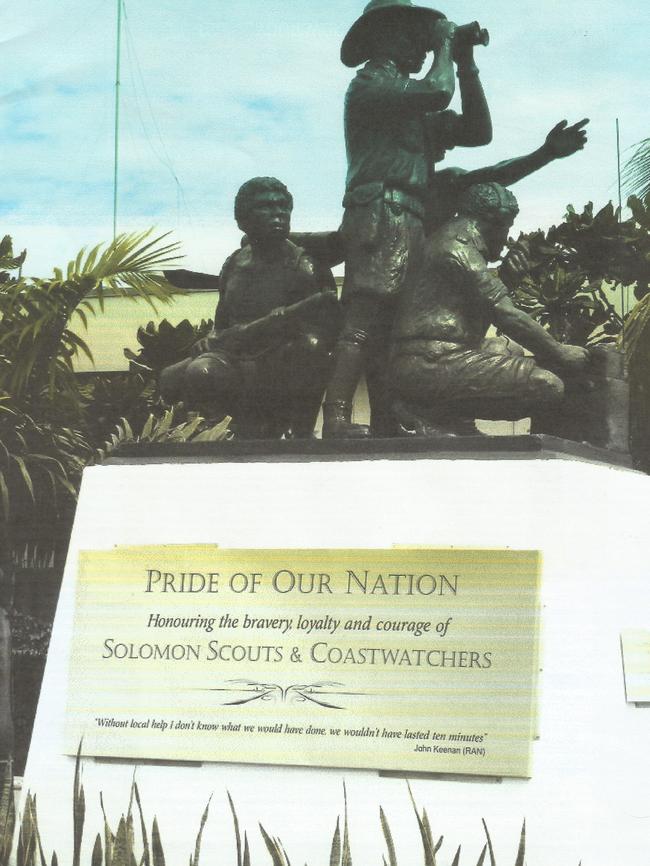

The official acknowledgement by five-star US Admiral of the Fleet, William F. Halsey, was brief and poignant: “The Coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal, and Guadalcanal saved the South Pacific.” A memorial recognising the role of the Coastwatchers stands in Honiara today.

In essence, if the Coastwatchers had not routinely signalled their warnings by Morse Code, such as those mentioned above, the consequences would have been dire.

Firstly, the capture of Port Moresby by the Japanese would have virtually severed US support for Australia and, using Port Moresby as a base, Japanese bombers would have been able to bomb Cairns -525 miles , Townsville, Mackay, Rockhampton and Brisbane - 1,297 miles, and block the eastern sea approaches to Darwin, only 1,126 miles away, thus ‘opening the gate’ for the invasion of Australia.

Had the Coastwatchers not alerted the Allies to the impending Japanese attack, Australians would not have been able to launch their Port Moresby offensive and thwart Japan’s thrust toward Kokoda. This offensive was crucial as it protected the operation base of courageous forces fighting in New Guinea, who would later fight on the Kokoda Trail and successfully repel the Japanese from their Buna, Gona, Lae and Sanananda occupations.

Subsequently, the combined forces of the US and Australia drove the Japanese from their strongholds at Lae and Salamaua, then Finchafen, Saidor, Madang, Aitape, Wewak, Hollandia, Biak, Wadke and Morotai.

If it weren’t for the Coastwatchers, the Allied Supreme Commander General Douglas MacArthur would have been constrained to defending the southern hemisphere disasters of Guadalcanal and Port Moresby. MacArthur would have therefore been prevented from redeploying his forces, who were instrumental in their successful island-hopping campaign, north of the Equator. MacArthur’s troops managed to reach and occupy Tinian Island where they launched the atom bombs that ended the war with Japan.

Thus, the Australian Coastwatchers turned the tide - to destroy Japanese General Sadao Araki’s aim to “be supreme in Asia, the South Seas and eventually the four corners of the world.”

The role of Coastwatchers at critical points in the war was also acknowledged by Allied Commander-in-Chief General Douglas MacArthur who stated in a Foreword to Eric Feldt’s book “They are officially credited with being a crucial and decisive factor in the allied victories of Gualalcanal and Tulagi and later on in the operations of New Britain.”

Apart from their vital intelligence gathering role however, the Coastwatchers also rescued 75 prisoners of war, 321 downed Allied airmen, 280 sailors, 190 missionaries and civilians, and hundreds of local people and others who had risked their lives for the Allies.

One of those rescued was US Navy Lieutenant John F. Kennedy, whose PT 109 Patrol Torpedo boat was carved in two by a Japanese war-ship and destroyed in the Solomons waters. After the sinking, the Lieutenant and his crew reached Kolombangara Island where they were found by Coastwatcher Sub-Lieutenant Reg Evans who organised their rescue.

In 1959, a memorial lighthouse was erected at Madang, on the north coast of Papua New Guinea, to honour the Coastwatchers. The memorial plaque bears the names of 36 Coastwatchers killed behind enemy lines while risking their lives in the execution of their duties. The plaque also bears this inscription: “They watched and warned and died that we might live.”

Ex-AIF Sergeant James Burrowes (93-years-old) served 4 years, including 2½ years as a signaller Coastwatcher in ‘M’ Special Unit of the Allied Intelligence Bureau, and 9 months with the US 7th Fleet Amphibious Landing Force. He spent 10 months in enemy-occupied territory over-looking Rabaul. Burrowes is the last signaller Coastwatcher survivor in Australia.