Already, it is impossible to imagine Hong Kong ever returning to quite the position it occupied before these demonstrations began a couple of months ago. Hong Kong is not now as important to the Chinese economy as it was in 1997, when mainland China took control of the former British colony, but it is still a key element of Chinese capital raising, corporate headquarters and interaction with the Western economy.

Hong Kong deserves to be considered for its own sake, for the lives and freedoms of its seven million inhabitants. But it is also important to draw out the international implications of what is unfolding. Already, events in Hong Kong inflict a terrible reputational stain on Beijing.

Every dictatorship suffers a permanent crisis of legitimacy. It is common today, and not entirely inaccurate, to talk of the crisis of democracy. But dictatorship is always in crisis.

In a democracy, a government that loses legitimacy can be thrown out by the people. A dictatorship that loses legitimacy can be thrown out only by civil insurrection, or sustained by repression. The Hong Kong government has lost legitimacy. That means the Beijing government also has lost legitimacy with the people of Hong Kong.

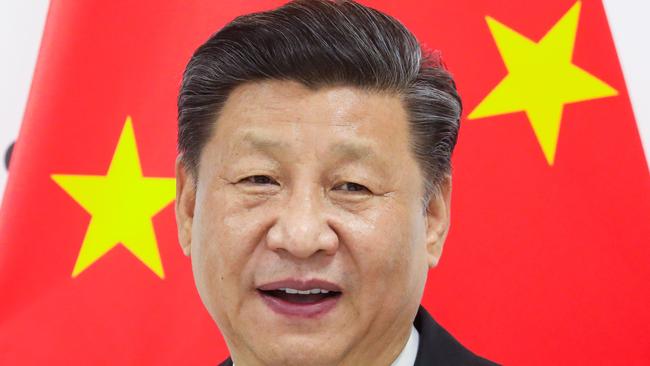

This is a tremendous blow to the prestige of Beijing and to the personal prestige of Xi Jinping. When he abolished term limits and made himself effectively President for life, and given all the other ways in which he has attacked the modest institutionalism that grew up under his predecessors, Xi fundamentally changed the direction of mainland Chinese political and cultural development.

He took it away from being an authoritarian regime with a good economic record, a good deal of civic space and on a modest and limited path of partial liberalisation. He headed it instead towards a new, hi-tech totalitarianism. Much nonsense is talked about the influence of Confucianism and Chinese cultural history on the government in Beijing. But above all else it is in reality Leninist. Its leaders, including Xi, spend years studying Lenin’s thought and actions. Lenin was the master of one idea above all others — the acquisition and maintenance of state power by and for the Communist Party.

The criticism of Andrew Hastie’s article about China is entirely absurd. Hastie’s intellectual point was acute. As Hastie argues, and as is irrefutable, the West believed that economic liberalisation would lead to political liberalisation, or at least moderation, in China. This simply has not happened. Instead, even the term “economic liberalisation” has become oxymoronic. Beijing has pioneered a kind of state-led and state-dominated crypto-capitalism, which is more truly than ever before now best seen as Leninist socialism with some capitalistic characteristics (to up-end the old Beijing phrase of socialism with Chinese characteristics).

Hastie’s striking comparison, the contemporary idea that economic liberalisation cured all strategic problems was functionally equivalent to French thought in the 1930s that the Maginot line secured all strategic threats, was creative and subtle and should not have been subject to the ridiculous abuse it received. It certainly did not imply equivalence between modern China and Nazi Germany.

It may well be the new directions that Xi has pioneered in mainland China itself, more than the slow strangulation of freedom in Hong Kong, has incensed and alarmed the people of Hong Kong.

The whole unfolding saga of Hong Kong demonstrates the importance of politics in foreign policy. It also demonstrates the extreme foolishness of Malcolm Turnbull and Julie Bishop in trying to foist on Australia an extradition treaty with China. This would have been an instrument of intimidation of ethnic Chinese and others by the state apparatuses in Beijing, which has already shown a wide range of disconcerting and unacceptable efforts to interfere in Australian politics and society.

This is not a general criticism of Turnbull and Bishop. They were an effective and productive foreign policy team and neither was, generally, a pushover for Beijing. But the attempt to ratify the extradition treaty was a terrible misjudgment. They were saved from this misjudgment by the reaction of Australian politics, of Liberal politicians such as Hastie and of the Australian Labor Party.

The Morrison government is understandably jittery about people such as Hastie making such frank statements. The Beijing government seeks to hold the Morrison government accountable for the statements of the Australian media and of Australian politicians. The Morrison government must simply keep repeating to Beijing that Australia is a free society and Canberra cannot control what free Australians say.

The demonstrators in Hong Kong have reasonable but probably unattainable demands.

They want the extradition treaty formally withdrawn, an inquiry into police brutality, charges against arrested demonstrators downgraded or dropped and universal suffrage for democratic elections.

Hong Kong’s terrified government would surely withdraw the legislation altogether if Beijing would allow it. This stark reality makes a mockery of the idea that Hong Kong’s government is independent in its local decision-making. The demonstrators and Beijing are locked in a battle of wills. Beijing cannot make concessions to the demonstrators or it acknowledges the failure of its rule in Hong Kong and it legitimises the demonstrators’ methods.

And despite its air of power, like most dictatorships Beijing is perennially scared of rebellion, discord and overthrow. Any ultimate peace with the demonstrators would have to involve some level of amnesty for most of those already arrested. Again, you would think the Hong Kong government would do that if it could.

An outside inquiry into police brutality seems less likely, as that would undermine the willingness of police to take tough action in the future if the government wanted them to. And Beijing once promised universal suffrage for the people of Hong Kong but has never delivered it.

While Western electorates, including Australia’s, are overwhelmingly sympathetic to the demonstrators it may well be that the demonstrators have made profound strategic misjudgements and overplayed their hand.

Paralysing the airport is almost forcing Beijing into action. That cannot be allowed to continue indefinitely. The demonstrators here are also doing something they have tried hard not to do — hurting innocent people, especially international visitors.

Beijing is reluctant to intervene in a heavy-handed way because of the enormous, permanent reputational damage it would suffer. More particularly, the US congress would be eager to impose severe penalties beyond anything Donald Trump has yet thought up.

Nonetheless, the bottom line is that Beijing will not allow its basic power to be undermined. The potential for truly terrible tragedy is immense.

Hong Kong, the pearl of the Orient, is right now the pivot point of global politics. In all its fabled history, perhaps its destiny has never mattered to the world more than it does right now. For the unfolding crisis in Hong Kong has the potential to affect fundamentally the relationship between the US and China for years, perhaps decades, to come.