If Hanks’s test of authenticity takes hold, some of the best actors may be limited to playing themselves. Worse, it will devalue one of the more important qualities that foster a tolerant society. Putting yourself in someone else’s shoes, understanding their life even when it differs starkly from yours, is the essence of empathy.

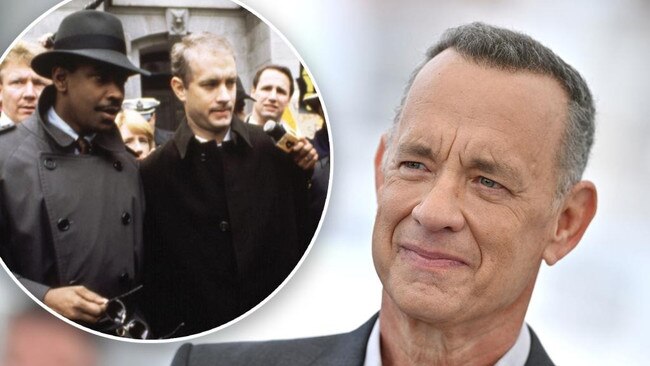

In an interview last week with The New York Times Magazine, Hanks is described, not unreasonably, as “an avatar of American goodness”. He has often played the decent man bumping up against injustice (Forrest Gump), showing judgment and courage (Apollo 13), challenging societal pressures (Bridge of Spies), saving lives (Sully). In Philadelphia, Hanks plays a gay lawyer with AIDS who stares down prejudice, and demands justice, by suing his law firm for wrongful termination. Lawyer Andrew Beckett struggles to find a lawyer to act for him and settles on a homophobic ambulance chaser named Joe Miller, played by Denzel Washington.

Exploring what it means to be authentic in Hollywood, Hanks said that today, people would not accept the inauthenticity of a straight guy playing a gay guy. “Do I sound like I’m preaching? I don’t mean to,” he added.

It is not surprising that preaching forms part of Hollywood’s schtick to reinvent itself. From sex scandals to productions showcasing almost exclusively straight white people, the movie industry needed a correction. But, as often happens, there can be an overcorrection, too. Hollywood has become a symbol of try-hard wokery where few are brave enough to push back against the latest fad. The authenticity movement, where only a gay person can play a gay character is, no doubt, driven by good intentions. But that is no guarantee of good outcomes.

Hanks is right about one thing, though. Authenticity matters. Just as in books, the characters who resonate down the ages tell a story that genuinely touches us about the wondrous, complex, frustrating human condition. It moves us in some way, to laugh, cry, feel, think, reflect. It points to a reality – be it a tragedy, a joy, a deeply human journey of some kind – some of us may already know about or one most of us may come to understand better from watching a film or reading a book.

Authenticity doesn’t hinge on a make-believe character being played by a person with the same experiences. To be sure, there may be some limits: a white character cannot sensibly be played by a person of colour, and vice versa. But there are no absolutes, even here. Witness Hamilton, where producers cast black actors to play the roles of white men and women from history to make a political point. Moreover, actors lose weight, gain weight, alter their appearance for a role because this is the essence of acting, of performing, of bringing to life a fictional, or even a nonfictional, character.

That is the beauty of make-believe. It depends on the magnificence of creative talents, writers, producers, actors joining forces to tell a story that envelops us, moves us, even changes us. A story such as Philadelphia, for example, broke new ground in the early 1990s by featuring a homosexual man as the lead character.

To be sure, a movie from decades earlier might be made differently today. As a writer for Smithsonian Magazine explored in interviews a few years ago, if Philadelphia were made 25 years later, it might be about people with HIV who were transgender, arrested and abused by the police and criminal justice system. It could be about a gay man of colour, coming from a poorer background, said another person. “He could be played by Denzel Washington,” suggests the author.

The problem with Hanks’s call for change is if we match a gay character with a gay actor, where do we stop? Poverty leaves deep marks on a person; why shouldn’t we match a wretchedly poor character with an equally poor actor? What about a cancer-stricken character? Hanks played the heartwarming and slow-witted kid Forrest Gump. Does that mean a clever man cannot play such a role in future? Does it mean only a former singer who reached dizzying success and then a descent into drugs can play Elvis?

As much as I admire Hanks, I have no desire to see a movie about a respectable white guy who is happily married and who won a few Oscars. Yet that is the upshot of Hanks’s authenticity movement – lots of biopics where the real-life people play themselves. A straight, white boy who aspires to be the next Hanks could only be cast to play a straight white man.

Though it doesn’t explain Hanks’s view – he is 65 – in part there is a generational divide about how to deliver authentic content. Much good has come from an impatient younger generation wanting to do things differently. It’s driven, no doubt, by a well-meaning focus on inclusivity, trying to place more actors from minority backgrounds in lead roles to make their experience more visible. The critics of Hanks’s view may be waved away as propagating a slippery slope argument rather than addressing the point in hand. If the argument is for affirmative action, then proponents may want to consider whether casting gay actors as gay characters will typecast them.

The bigger point is that the generational search for greater inclusivity misunderstands the magical world of make-believe and mistakenly assumes genuine empathy can come only from shared experience. Empathy means more than that. Being able to step into the shoes of others with different experiences, to understand them better, is the essence not just of a great fiction and a great movie but of tolerance.

The new authenticity measure in Hollywood echoes attempts in publishing to cleanse what some publishers and critics have deemed cultural appropriation. Lionel Shriver, attacked for writing about people outside her own experience, has pushed back, pointing out where that leads. But who will challenge this trend in movies? If not Hanks, then who?

No, not Tom Hanks. Anyone but Hanks. We would expect it from the loopy Tom Cruise. And the preening George Clooney, too. But Hanks? Sadly, the star who features in the new movie Elvis has succumbed to the misconceived idea that today only a gay actor could play the role that earned him an Oscar in the 1993 film Philadelphia.