No case for the Indigenous voice goes for the jugular, while Yes fails on presentation

Australians have got a sneak peek of the Yes and No arguments for the voice referendum.

The Australian Electoral Commission has taken the sensible, if unprecedented, action of putting them online before they are printed and sent out to every household via snail mail.

The arguments represent the best that each side can put forward. They reveal a polarised vision for Australia characterised in the Yes case by hope and unity, and in the No case by risk and division.

Each case is limited to 2000 words of black-and-white text. Visuals or anything else to make the material more engaging is not permitted. Unsurprisingly, the document comes across as wordy and unappealing. Many people will be turned off by what looks to be a dry and boring read. Others will be repelled by the structure of the pamphlet in having two sides shouting at each other.

Australians also will find the pamphlet challenging because it lacks neutral explanatory material to help them evaluate the arguments. The pamphlet will contain the textual change to the Constitution, but this will not be enough.

Few people will have the knowledge to resolve questions of executive power and judicial review, or even more basic issues such as what the voice can make representations on. Voters will need to make a judgment without being able to evaluate the material.

The task is made even more difficult because there is no requirement for the Yes and No cases to be accurate. The AEC has been at pains to emphasise its job is merely to receive the text written by politicians and not to check they are correct. As a result, past pamphlets have been full of wild exaggeration and misinformation because this can prove more influential than the truth.

In a positive development, there is less misinformation in this pamphlet than some past versions. For example, the Yes case in 1944 promised the referendum on post-war powers for the commonwealth would “abolish poverty and unemployment” and guarantee “no more depressions”.

On the other hand, the No case in 1913 argued that giving the commonwealth power to regulate monopolies would lead to the “adoption of socialism”, with the government able to “preside as dictator”.

Hyperbole is less evident for this referendum. However, there are still inaccuracies and questionable assumptions. The Yes case seeks to combat the claim that Australians have not been given enough detail by stating that the voice will be a “committee” of Indigenous people chosen from their local area who will serve a fixed term. This is a reasonable assumption and may prove to be true, but the Yes case fails to mention that this will be determined by parliament after the referendum.

The No case also has its problems. It states that “no issue” is beyond the reach of the voice, but the change to the Constitution states that the voice may make representations only “on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”. The No case also says previous referendums have been preceded by a constitutional convention and implies this referendum is exceptional in missing this step. However, very few referendums have had a constitutional convention, so this referendum fits the norm.

The Yes and No cases are exercises in persuasion. I’ve read many of the past pamphlets since they were introduced in 1912, and my sense is that the No case in this referendum makes better use of the format. The Yes case is positive and on strong ground in pointing out how the voice will recognise our first peoples and enable institutions of government to listen to their views in a way that will improve lives. It also has good arguments on how the referendum can unite the community and save taxpayers’ money.

The No case goes for the jugular in highlighting emotive arguments that may cut through with voters. It does so by drawing on the playbook of past campaigns.

One example is how it empathises with people who want to help Indigenous Australians and support constitutional recognition. It gives them permission to vote No by marshalling a set of arguments to justify this choice.

This “Yes, but” approach was effective in the 1999 referendum in attracting committed republicans to the No case.

The No case also uses rhetoric from past campaigns. A good example is the slogan “if you don’t know, vote no”. This encourages people who are left confused and uncertain, or simply cannot be bothered to learn more about the proposal, to cast a No vote. It can prove very effective once the No case has made a lot of noise and left Australians confused.

The slogan was the first argument in the No case on the preamble in 1999 and is the closing argument in the No pamphlet on the voice.

The No case is also assisted by doing a better job in presenting its key points in the constrained format. Many Australians will read only the headings and may not read past the first page of each case. This makes the opening statement of critical importance. The Yes case has a lot of words on its first page in a messy format that does not do justice to its strongest messages. On the other hand, the No case has its central arguments leap from its first page in big bold letters with RISKY, UNKNOWN, DIVISIVE and PERMANENT.

The government and Yes case can take consolation from the fact the pamphlet will not be as influential as its $10.6m price tag suggests. Few Australians will read the document. Some will mistake the pamphlet as junk mail, while others will baulk at the idea of 4000 words of unadorned text on the voice.

During the 1999 referendum I asked my constitutional law class of 140 students who had read the pamphlet. Many had begun reading but were put off and stopped at the early pages. Not one had read it cover to cover. We can expect a similar response this time around.

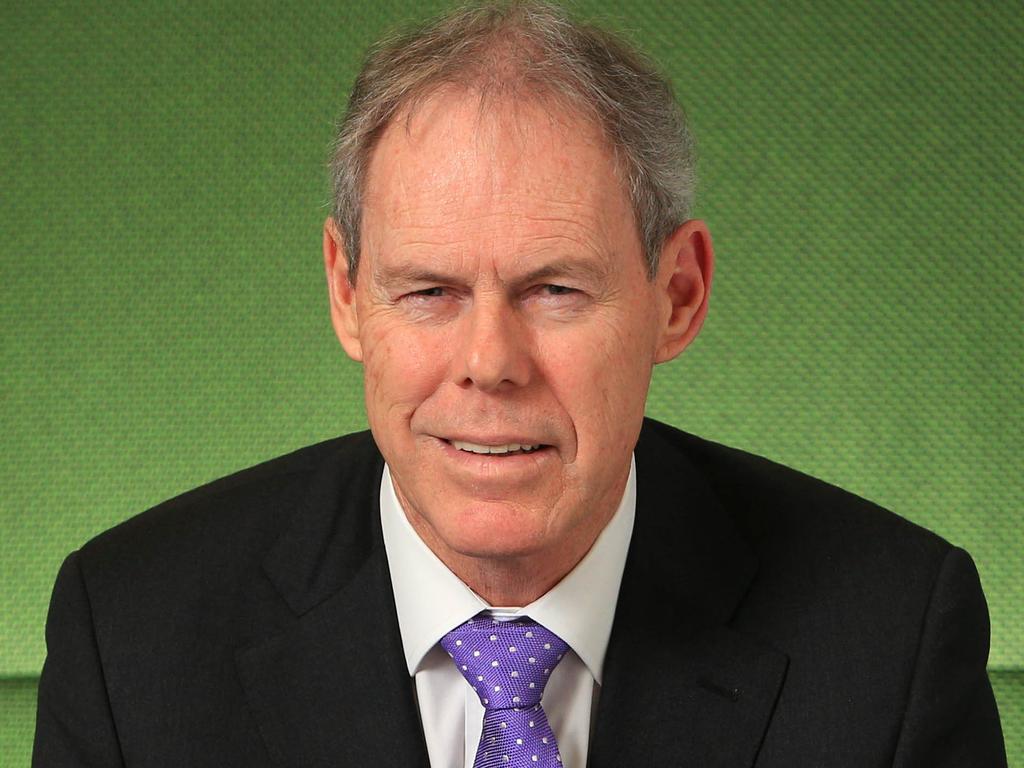

George Williams is a deputy vice-chancellor and professor of law at the University of NSW.