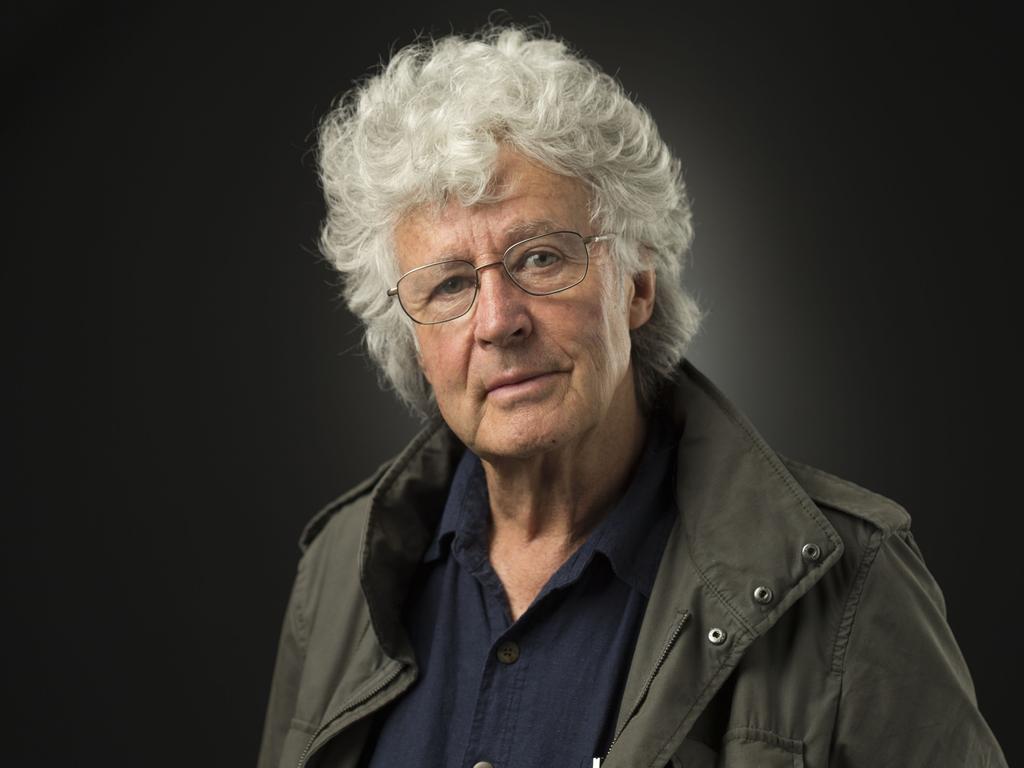

So there he was, propped up in bed, a living clue to something that lay at the heart of Michael’s most beloved cartoon characters. Old Mr Leunig had a prominent nose, gentle eyes and a wistful smile. Here was Michael’s mythical hero; the vulnerable old working-class man who had managed to defend himself and his family against the crazy, arbitrary, bullying materialist world.

When I suggested this, Michael vaguely agreed. Perhaps the connection had never occurred to him.

These were the days when The Age had hired a roomful of cartoonists and illustrators: Leunig, Peter Nicholson, Ron Tandberg, Les Tanner, Arthur Horner and me. We had a lot of fun.

Leunig was the leader of a developing expansion of graphic possibilities. Huge broadsheet spaces, full colour and cheerful editorial encouragement. Whenever our enthusiasms extended into the world of fine art the product was brought back to our newspaper work (printmaking, painting and sculpture).

The cartoon room was a wall-to-wall cigarette fog of concentrated activity. Occasionally you noticed that someone was chuckling. Michael often laughed as he drew, as if Mr Curly’s ducks and humble triumph were emerging on the page by surprise.

Everything was not plain sailing, however. In the early 1980s Michael was asked to do some political cartoons for the editorial page. One night, in utter frustration with the apparent meaningless blather of political fashion, he produced a picture of a man flying across the sky on a burning bed. A disgruntled night editor complained that “Leunig has to decide if he really wants to be a political cartoonist”. Everyone loved the cartoon as a moment of liberation from po-faced “serious” commentary.

Sometimes the stress got the better of him. One night I heard him curse and then crush his nib into his desk before storming off. I actually included that stubbed nib in a portrait I did of him years later.

After this huge creative outburst, Michael started to move away from the office and into other art forms such as music, poetry and film. He made many friends in this world and in days to come we’ll no doubt hear many stories and tributes from that part of his life.

Michael never strayed too far from The Age that had given him such wonderful opportunities. However, his relationship with the paper gradually deteriorated. I had a lot of contact with him during this period and I believe he was treated disrespectfully. He was eventually forced into the humiliating position of regular rejection of his work for the sin of “ inappropriateness”.

Michael had indeed rejected much of the woke left and finally succumbed to cancel culture. First he was banned from the editorial page, then through a painful, baffling attrition was irregularly confined to Saturday only. He made unsuccessful attempts to get some clarification of the amorphous rules that were applied to him. Then he was sacked.

The whole episode was a travesty of the pluralistic ideals of journalism.

Michael and I came to agree on our disillusionment with much of the left’s extreme social agenda, including the hysterical exaggerations of the global warming brigade. We often vehemently disagreed over foreign policy issues such as the Middle East, in particular. These disagreements periodically caused a cooling of our friendship.

But real friendship can be like that. Real friendship can survive these eruptions through civility, patience and laughter. He was the funniest person I’ve ever known. Years of acrimony can be abolished by non-stop laughter at the absurdity of our failures and ludicrous mortality.

A mutual friend and colleague, Martin Flanagan, has asked me to describe Michael’s greatest achievement. I would say that he had a unique creative genius. Through humour and art he touched the most precious aspect of many of our lives: an appreciation of the mysterious awesomeness of human existence. No small achievement.

When cornered by the harassment of political drudgery, he had the happy knack of diverting attention to the transcendent miracles of music and poetry. So, his overall achievement was to adorn the prosaic materialist world of journalism with art. He described himself as a people’s poet for troubled times. He will be sadly missed by his partner Nicola, his children, friends and fans.

John Spooner is a cartoonist who worked for 40 years at The Age and now has a safe haven at The Australian.

Many years ago my friend Michael Leunig said to me that his father was ill and in hospital. Would I like to meet him? “No problem, let’s go.”