Muzzle speech, and there’s no telling where restrictions will end

But it is important to remember two key principles on the subject of freedom of speech. The first is that any incitement to violence against any individual or group in the community is a criminal offence at common law and always has been. It also may be an offence under various statutes in some of the states and territories.

The second principle is that restrictions on expressions of opinion, however offensive those opinions may be to some – or even most – members of the community, are essentially attempts to suppress debate on political, social and economic questions.

Some of the opinions expressed in political debate may be outlandish on occasions but most members of the community seem to exercise a healthy degree of scepticism about political issues and it may be expected that fantastic notions will fall by the wayside.

As American jurist William O. Douglas said in the early 1950s: “When ideas compete in the market for acceptance, full and free discussion exposes the false and they gain few adherents.”

As already noted, some of these opinions may be offensive to certain members of the community. This is not to encourage a brutal style of debate but sometimes there are strong differences on political issues and some people are unduly sensitive to criticism. As British jurist Lord Sumption said only recently: “No one is entitled to intellectual safety.”

This is the vice of section 18C of the federal Racial Discrimination Act. It makes unlawful expressions of opinion that, among other things, are offensive or insulting to various groups in the community.

It will be said that there are defences available in these kinds of provisions but they are subject to subjective standards such as reasonability and good faith on the part of the publisher.

In any event, mounting a successful defence may be small consolation to a publisher who does so only after spending years and large sums in legal costs in proceedings before the Australian Human Rights Commission or the Federal Court.

The vice in the federal government’s Combating Misinformation and Disinformation Bill 2023 is that it would effectively enable the Australian Communications and Media Authority to supervise social media platforms such as Google and Facebook to prevent the posting of what is described as misinformation and disinformation.

The bill, which apparently is to be revised, although seemingly not in its major goals, inevitably would lead to the suppression of opinions on political, social and economic issues. It is only necessary to think of a subject such as climate change to see what the scope is for the quashing of unorthodox opinions.

The same fallacy – that opinions somehow can be treated as statements of fact – underlies the push for so-called truth in political advertising. How reasonable it seems at first blush to say that political parties in their campaigns should be as responsible for false statements as the manufacturers of dishwashing fluids in their advertising.

But how easy would it be to use this kind of legislation to close down political debate on contentious questions such as the economic costs and benefits of migration? Again, this proposal really is aimed at expressions of opinion and not statements of fact.

In many ways the more offensive opinions are to the vast majority of the community, the more important it is that they be allowed to be expressed and meet with the rejection of that community.

It is easy to say that Nazi symbols should be banned because they are an absurd expression of political opinion and are overwhelmingly rejected by our society. But once restrictions on freedom of speech, however unattractive that speech, start to be imposed, it is hard to estimate where those restrictions may stop.

That is because the opponents of freedom of speech in our society have no tolerance for contrary opinions and will take any opportunity available to close them down. Free speech is an important legacy of Western civilisation and needs to be jealously guarded from those who wish to confine public debate to one set of opinions only – naturally their own.

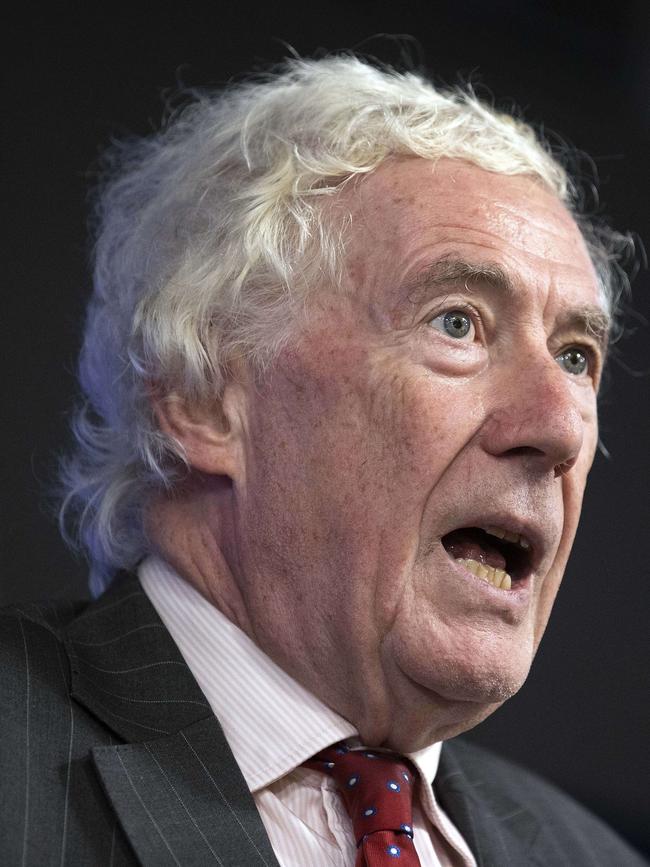

Michael Sexton’s latest book is Dissenting Opinions.

There have been a lot of references to freedom of speech in recent weeks, sparked by the series of demonstrations over the conflict in Gaza, and some discussion as to whether these kinds of gatherings, by groups on either side, should be allowed at all.